The Poet’s Nightstand

The Poet’s Nightstand with D. A. Powell

In The Poet's Nightstand, we ask poets to talk about five books that have made a big impression on them recently. D.A. Powell kicks off the series with his reflections on collections by Jorie Graham, Regan Good, Wayne Holloway-Smith, Simone Savannah, and Paisley Rekdal.

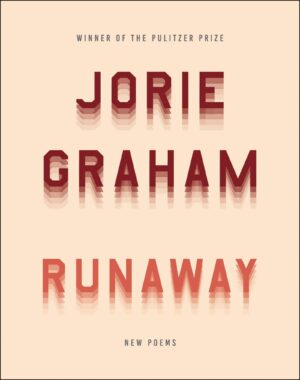

Jorie Graham's allusive, monumental poems scare the daylights out of me, the mind on high alert for changes in sea and body, land and soul, the vigilance of a faithful apostle waiting at the tomb for something beyond all this world. Her latest book, Runaway, is a deep puncture, a mortal ache somewhere between prayer and science. Or do I mean faith and silence. It is light wavering between here and gone. I turn to/return to her poems so often; I have felt their gravity so close to my own and am arrested by it. "Your chest a pulsation," the speaker inside the poem says, "A languishment that will not (and here there is the silence at the end of the word compounded by the silence at the end of the line compounded by the silence at the end of the stanza) die." All the drama in that silence—the hesitation, the consideration, the weight of one word waiting on the tongue to be spoken—gets further complicated, followed as it is by a rhetorical question that cannot be answered by the living: 'what is die." I feel the whole earth shift under me at night while I am reading these poems, the immensity of it, the certainty and uncertainty of it.

Purchase Book

I don't know how long I've had The Needle on my nightstand, but this collection by Regan Good gets dipped into late at night, like having a spoonful of honey from the jar. Like Marianne Moore, Good keeps the language brilliant as any sapphire, as when the magnolia's ancient heady blossoms "compacted fragrant whorls of white shot forth." I can feel the motion and mechanics of the flower's bud in the syllables but also see it inside the lids of my eyes. Birds don't merely fly in the space of these lines they "pulse like globs of molten metal streaking off a sun." I feel like I'm learning a new language for wonder. There are seascapes and landscapes for real but there are also the glass flowers of the Museum; these painterly renderings of what we refer to as the natural world caught somewhere between the horse and rider, the ship and the water, the subject and the artist. "Heavenly description, of things fluted and feathered / things flying liquid and high / they cleave and cluster...." I am undone.

Purchase Book

There are two new collections that I read so I can feel that thump in my chest like "somebody just said something real." You know what I mean? Like you need other people's tea to remind you of all the tea you still need to spill. One of these is Wayne Holloway-Smith's Love Minus Love, a sequence of poems that kind of sear the flesh, typographically inventive at times (so hard to represent within a paragraph what's happening so I have to break the paragraph here to insert this slender poem):

what

is

the

least

a

person

can

reduce

themselves

to

maybe

I'm sorry

or

It feels very intimate, this book, with its bracketed asides whispering to us "[the 'he' could refer to either the father or the son in other / words the son could be dead and not know it]" and its sad haunting beauty. I heard Holloway-Smith read once, standing in a gallery in Peckham with no furniture, everyone on the concrete floor and I remember the way the poems seemed to ricochet down into the room and how still everyone sat and I thought, "why aren't these people screaming his name and throwing their panties at him," because those poems really were sexy and bare and powerful. But of course the British don't throw panties. They call them simply 'pants' or sometimes 'bloomers.'

Purchase Book

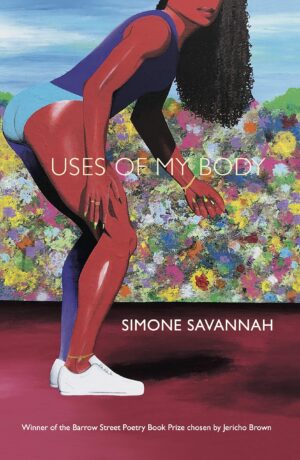

The other new collection that I'm smitten with is Simone Savannah's Uses of My Body. These poems emanate from someone sex- and body- positive, a woman who's not afraid to talk about dick and pussy. Not merely to be shocking, kinky or even funny (though those are all good uses of names for genitals, in their time) but also to reclaim one's own jurisdiction over what goes down, to assert boundaries around ones own personhood, to say "being / beautiful being black and a woman is difficult. / I must be deliberate I know now. Men (mis) read my dissertation / my poems / want to fuck me." There are moving elegies to Savannah's mother, as well as poems about dance and desire. We are treated to the writer's body through her careful curation, just as the locations and the eyes remain hidden in nude pictures, some things are cut out at the discretion of the sender. This is a book of autonomy as much as anatomy. Savannah says, in the first poem, she wanted to write "something that speaks / to the way I am actually built/have moved and pushed / have drenched myself in sweat." I find her voice so refreshing, and the poems: vital.

Purchase Book

And then finally a book that has been out over a year but which keeps me returning to its timely pages, Paisley Rekdal's Nightingale. The central sequence of the book concerns Philomela, whose story is told by Ovid in the Metamorphoses. Philomela is raped by her sister's husband who then cuts out her tongue so that she cannot tell. She therefore weaves a tapestry to reveal the hideous event to her sister, Procne. She is saved from the wrath of the sister's husband by being transformed into a nightingale. Rekdal isn't simply recounting the story; she is also addressing sexual assault from first hand, all while weaving her own tapestry of revealing. The whole book endures the violence and suffering of retelling, is itself a form of fighting back, ending in a scattershot of birds, the echo of Procne and Philomela's transformation and escape. But this is not the only story recounted. You must read the whole book and in the order in which it's organized to truly absorb the enormity of it. And there is beauty here, too, gorgeous passages that ring true as belfry bells: "what other streams could run as cold / what trees bloom with darker fruit?" This one is not a book for going to sleep but for waking.

Purchase Book