In Their Own Words

Carlie Hoffman on “Inventory”

At sixteen I worked at a Build-a-Bear in the mall,

stuffing the soft skins

of teddy bears. During my shifts

I sat by a big machine as children lined up

like cars in a drive thru, or hungry mouths

at the counter of my grandparents’

luncheonette in Liberty, New York,

in between wars.

The children looked like children. I wore

a denim button-down and khaki pants. Before stitching

each animal shut, I’d pluck a tiny, satin heart

from a plastic bucket like

a pomegranate seed.

One child made a wish,

then another. It was not for me to ask

what the wish was, only to gesture

to where within the cavern the heart would go.

After closing, just as spring

shadowed the parking lot with the first signs,

I’d bring a pencil and notepad to the back of the store

and take inventory: shelves of toy animal skins stacked

on metal scaffolding—young men sleeping soundly

in the barracks—the stockroom

a cathedral in repair.

Beneath muffled light, I count the hairs

sticking to bottles, the second

used condom, seeds in a pomegranate.

Within his glassy dome, snow is falling

as Hades takes Persephone

deeper inside the replica of girlhood.

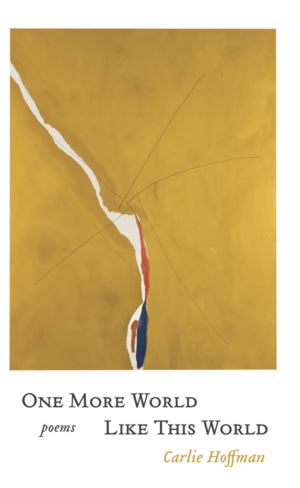

Reprinted from One More World Like This World (Four Way Books, 2025). Used with the permission of the publisher.

On “Inventory”

The story of the word inventory begins with the Latin invenire, meaning to “come upon,” “find,” or “discover.” At some point invenire took the form inventarium, whose definition evokes the written word: “a list of what is found.” In fifteenth century French, inventarium became inventoire, denoting the uses we know of today: Listing, recordkeeping, summarizing, arranging, counting, accounting, and so forth.

Recordkeeping features in the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter,” the earliest known telling of the Persephone myth. The poem is a unique illustration of the importance of recording one’s own life and experiences, especially because it is a record of Persephone’s disappearance.

The poem begins with Persephone counting flowers: “roses, crocus, and beautiful violets.” She gathers her arrangement “up and down the soft meadow” when, all of a sudden, Hades comes upon her in his chariot and steals her into the underworld. However, it’s not really all of a sudden. We learn that Persephone’s father, Zeus, has prearranged for his brother, Hades, to take Persephone as his bride. Persephone herself becomes part of Hades’s inventory.

The poem’s taking stock of events illuminates the predicaments that imperil Persephone’s innocence. Homer’s Persephone carries an inventory of assorted flowers that double as a bride’s bouquet and mourner’s offering. The speaker of my poem considers similarly shifting perspectives on her own experience entering and exiting girlhood through a myriad of inventories: children lined up at Build-A-Bear, the store’s stock room, animal skins, hairs that stick to beer bottles, pomegranate seeds.

My poem also engages with the world beyond the stockroom, as in: “hungry mouths at my grandparent’s luncheonette in Liberty, New York, / in between wars” and “young men sleeping soundly in the barracks.” It takes place in a toy-making factory where children create stuffed teddy bears in their own images, a mirror world akin to Hades’s underworld. It is in this context that my poem explores the imagination’s ability to connect our own stories to other people, places, lives, and experiences. My poem also highlights the importance of keeping an inventory—claiming ownership—of one’s own story. Persephone’s record begins with her curatorial practice choosing the flowers: “Iris blossoms too, [Persephone] picked, and hyacinth.”