In Their Own Words

Rosa Alcalá on “You, the Body & the Book”

You lived with the body. There was no room for the book. You lived with the book, and the body broke a window trying to get in. You let the body stay the night on the couch and cleaned the cuts on its hands. The book said, I’m not jealous, but soon it begged for attention. At the poetry reading they both showed up and it was an impossible choice. In bed it was either the book or the body. At times zaftig, at times skinny. Neither of them looked better in the morning. You wiped their smudges after they got drunk and cried. Other books looked on smugly, cool and contained. They were all epiphany and apostrophe. The book made the body do impossible things, but only the body could bear another body and that was the question on the table. For a while you had very little to say to the book and worried the body was all you had.

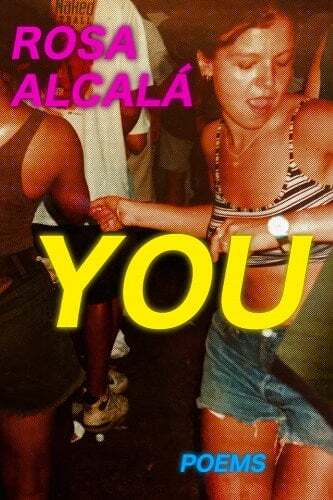

From YOU (Coffee House Press, 2024). Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On “You, the Body & the Book”

Muriel Rukeyser was a prolific writer. By the time she was 55, the age I am now, she had published fifteen books of poetry and many more in other genres, including translation. Plus, she had written plays as well as film and radio scripts. I will not compare my own productivity to hers, probably no one should. But when I look at her bibliography and see among the almost yearly book publications a gap of almost a decade, I am reminded that in the absence of new books, was the presence of a son. It was a gap in which she was bathing and nursing him. In which she, a single mother, was raising him on her own. Of course, so much could prevent a writer from completing a book. That gap could indicate a prolonged illness or financial precarity, a love affair or other pursuits, lack of inspiration or institutional recognition, a full teaching load. Kate Daniels argues that Rukeyser’s “low profile” during this period of her life had also to do with the anti-Communist witch hunts of the 1950s, of which she had been a target.[1] For me, the decision to have or not have a baby—coming on the heels of living for years with very little economic and personal stability—felt intimately tied to whether or not I could bring a book to fruition. I worried that one would preclude the other. In any case, this is what happened: I didn’t publish my first book of poems until I was 41. I didn’t have a baby until I was 40. The “until” was an external judgment I had fully assimilated into my being, heightening the stakes of choosing one over the other.

The dilemma that “You, the Body & the Book” posits goes beyond this one particular choice in time, of course. The question of how to negotiate the complexity of day-to-day existence with the desire to write remains even when the contingencies change. Now postmenopausal, I continue to look for answers in the bodies of work and the working bodies of poets I admire. I ask, how did they live, the poets, with a body, especially one marked female or otherwise disenfranchised? What negotiations, refusals, capitulations took place in that inescapable dependency of body and writing?

Currently steeped in the work of Muriel Rukeyser, I imagine her through her words, on a boat fleeing Barcelona at the onset of the Spanish Civil War[2], or standing “in the mud and rain of the prison gates—also the gates of perception, the gates of the body,”[3] protesting the imprisonment of South Korean poet Kim Chi Ha. But I also imagine her through the ways others have described her physical presence. Denise Levertov writes, of first meeting Rukeyser, that out of a “crowd of dark-suited irritable middle-aged men holding sherry glasses and looking at their watches” emerged “the tall and massive woman who was Muriel—she came welcomingly towards me on thin legs, like a large water bird.” She also describes her, in another moment that same evening, as “a tall, leonine woman, a genuinely sibylline presence.”[4] If you listen to the recording of Octavio Paz and Rukeyser reading together in an event organized by the Academy of American Poets in 1966[5]—her translations following his poems—you get a sense of the majestic presence Levertov describes. No matter that the syllables per line of her English translation have fallen short of the Spanish original, Rukeyser’s voicing expands with breath the body of each word, in turn lengthening the line and filling the space between herself and the listener. It is another type of translation, a searching after form that releases from Paz’s controlled, almost clipped, reading of his poems the monuments to air and light contained within them. We get a better sense of what it is to read Paz in the Spanish by hearing Rukeyser reading, in her voice, her translations to English.

I listen to a later Rukeyser reading[6], in 1979, the year before she died, and hear a different body reading, one diminished by illness, but a little warmer, and more vulnerable, more intimate, funnier, than in the Paz reading, but nonetheless powerful. A presence that doesn’t need to compete or stand as equal to someone else’s: herself “split open” to her listeners, a lowering of the mask.

Rukeyser’s voice in this later reading reminds me that there is no projected self of the poem without the fragility of our own physical existence and that no book is written without this fragility. Yet, somehow the “you” I was addressing in “You, the Body & the Book” wanted to live as a mind unburdened by the complications of a body or the cultural and literary expectations that come with it. Maybe the “you” was looking for transcendence. Maybe she wanted to live like the famous novelist who once told her, as a kind of ethos every serious writer should adopt, that he devoted many hours of each day to reading and writing and allowed no other distractions. (I could not see then that to be apportioned equal time and space for my own intellectual and creative nourishment I needed more than his ethos or daily routine; I needed his money and privilege). Or maybe the “you” wanted to just live as an “I” in the poems of her own creation, where she was free, as does Julia de Burgos in her poem “To Julia de Burgos,”[7]

where she addresses and denounces her own “you,” the bourgeois woman others perceive her to be. This “you” is not her true self, Julia de Burgos claims in the poem; the real Julia de Burgos is the “I” of her poems and it is this “I” that will lead the mob, torch in hand, to her imposter, the one trammeled by society’s expectations of a woman of her class. This “I” will burn her house down. In contrast, I approach my own “you” in this poem with all the tenderness and empathy gathered over time, to begin to understand these divisions between body and book, between person and poet, between need and need, impossible to reconcile, especially in a poem.

[1] Kate Daniels, “Preface: ‘In Order to Feel.’” In Muriel Rukeyser: Out of Silence. Ed. K. Daniels. (Evanston, IL: Triquarterly Books/ Northwestern UP, 1994.)

[2] “Mediterranean,” p. 144-151. In The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser. Eds. Janet E. Kaufman & Anne F. Herzog (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2005).

[3] “The Gates,” p. 561-668. In The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser.

[4] Denis Levertov, “On Muriel Rukeyser” in How Shall We Tell Each Other of the Poet?: The Life and Writing of Muriel Rukeyser, Ed. Anne F. Herzog and Janet Kaufman (NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1999).

[5] Octavio Paz with Muriel Rukeyser and Paul Blackburn, Academy of American Poets Reading (April 21, 1966). Accessed: Woodberry Poetry Room, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[6] Muriel Rukeyser. Recorded at Harvard University, Boylston Hall Auditorium (Apr.26, 1979). Accessed: Woodberry Poetry Room, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[7] Looking for a link to the poem to include here, I was astounded to find this performance of the poem’s translation as part of Leonard Bernstein’s 1977 Songfest.