In Their Own Words

Cynthia Marie Hoffman on “The Music of Language Is Clamping Down Hard”

The Music of Language Is Clamping Down Hard

Your sister has spotted the

woodpecker through the kitchen window. Every thought has a rhythm. The window,

like all windows, has six lines: the lines around the outside and the X you

draw in your mind, corner to corner. The forest is a thick enchantment of

green. You’re in your bare feet. Everyone leans toward the glass. You are just

a girl in the summertime drawing the window in your mind: one two three four

five six. Then the red flash of bird. Isn’t he humongous, your mother

says. Big as a cat. Isn’t he humongous works on the window. Put the

words on the window. The woodpecker clutches the feeder swinging by a rope. One

two three four five six. Think again, isn’t he humongous. At your

shoulder, your sister is normal, simple. But the music of language is opening

up for you. The music of language is clamping down hard. When the woodpecker is

gone, two slender birds sit together on a branch facing opposite directions, marking

an X with their tails in the wide green glass.

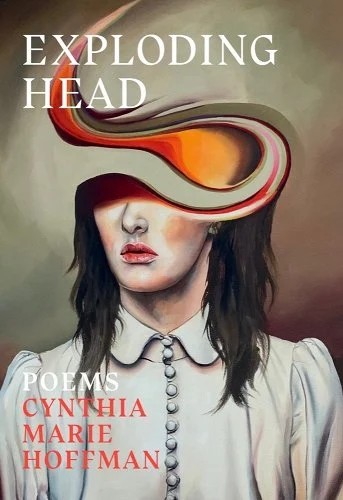

Reprinted from Exploding Head (Persea Books, 2024) with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “The Music of Language Is Clamping Down Hard”

“The music of language is opening up for you,” this poem

says. “The music of language is clamping down hard.” This is the best way I can

sum up my relationship to both poetry and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

I’m not sure the two can be separated.

From my memoir-in-prose poems, Exploding Head, this

poem tells an early part of my story. I was “just a girl” when my mind latched

onto numbers, patterns, and snippets of language. Where I grew up, in northern Virginia,

we would sometimes see Pileated Woodpeckers. They measure up to 19 inches and

sport a flame-red crest atop their heads. My mother hung feeders from the branches

with a complicated pully system at the edge of the forest and took great pride

in watching the action through the kitchen’s bay window.

I was “just a girl,” but I was already in the throes of ritualistic

counting (silently in my mind, so no one knew) and mapping patterns onto objects

in my field of vision. Windows were significant and allowed me to apply a count

of 4 (just the edges) or 6 (the edges plus an X across the middle).

So, when my mother says, “isn’t he humongous,” referring to

the woodpecker, something in my mind snatches that phrase out of the air. I don’t

intend to hear it. But the six-syllable phrase sounds as obvious to me as a monarch

looks flitting through the air. The six-syllable phrase is the butterfly in my

net, turning frantically in the cramped captivity of my mind.

Poetry is music to me. I studied music theory years before I

learned about iambs and trochees. I played piano and guitar. My ears perked up

when anyone spoke with inflection. On Sundays, I sang hymns, I listened to the

sermon, and I couldn’t decide which music I liked better. Poetry enlivens and

enables my mind to work the way it does and allows it to be useful. This part

is the “opening up.”

My father tells a story about his music teacher who had

perfect pitch. One day, mid-lecture, the chalk squeaked against the board. The

teacher whipped around excitedly to face his students. “What note was that?” he

asked. It was a B♭.

Like that music teacher, I can’t turn off my awareness of the

musicality of language, even when it crops up at inopportune times. On web

meetings at the consulting firm where I work, I crack a smile with the pure joy

of hearing something perfectly alliterative or accidentally rhymed. My mother

has a habit of doing this, too, going so far as to interrupt the speaker to sing-song

the rhyming phrase back. It’s like people who constantly correct your grammar;

not everyone gets the same kick out of it. Perhaps some of this joy is innate;

perhaps some of it is learned.

A lot of it is OCD. That part of me that can’t let go, that

keeps the butterfly frantically turning in the net, that is OCD.

You’d think I’d write in syllabics and metered verse. But recently,

a workshop leader included syllabics in the writing prompt, and it immediately

triggered my OCD. I wrote one seven-syllable line, and then I just sat there,

reading that line again and again, settling into a mind-numbing trance where no

creative thinking can occur. I read that line so many times, it shed all

meaning but seven. It became a row of percussive beats. I tapped the drum seven

times, and seven times again. Until finally a bell dinged, and the writing

session was over. That part is the “clamping down.”

This poem is also about how different my secret syllabics-obsessed

rituals made me feel from those around me. The “X” marked across the glass

feels important to me because an X is something crossed out, something bad, a

wrong answer. I was the bad thing. OCD was the wrong answer.

And an “X” is made of two lines headed in completely

different directions, like my life and my sister’s: our lives cross at one

point, but we’re on opposing paths. My path, perhaps inevitably, led to poetry.

I only realized many years later in adulthood, as I worked to

“solve for X” in my personal OCD equation, the “X” on the window is not all

bad. It represents something I crafted out of nothing. It’s the part of my

brain that found creative ways to map language into forms—an act similar to

that of writing a poem.