In Their Own Words

A. E. Stallings on “Ajar”

Ajar

The washing-machine door broke. We hand-washed for a week.

Left in the tub to soak, the angers began to reek,

And sometimes when we spoke, you said we shouldn't speak.

Pandora was a bride; the gods gave her a jar

But said don't look inside. You know how stories are—

The can of worms denied? It's never been so far.

Whatever the gods forbid, it's sure someone will do,

And so Pandora did, and made the worst come true.

She peeked under the lid, and out all trouble flew:

Sickness, war, and pain, nerves frayed like fretted rope,

Every mortal bane with which Mankind must cope.

The only thing to remain, lodged in the mouth, was Hope.

Or so the tale asserts— and who am I to deny it?

Yes, out like black-winged birds the woes flew and ran riot,

But I say that the woes were words, and the only thing left was quiet.

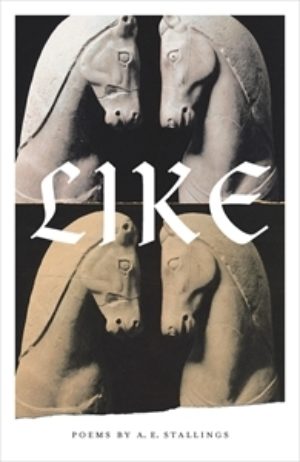

From Like (FSG, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Ajar"

"Ajar" was written while I was translating Hesiod's Works and Days, an archaic Greek poem-cum-almanac about justice and farming, chores and the seasons. It also contains a story about the first woman, Pandora, and is the first telling of Pandora and the Jar. Except frequently I was stuck on the translation, progress was slow, I had my hands full with a young child and a toddler, not to mention the endless drama of Greece during the financial crisis, a constant background unrest in the city around us.

So sometimes instead of making headway with the translation, I ended up writing poems about Hesiod or obliquely inspired by him. It turns out, I also have a history of writing poems about laundry—(my first book, Archaic Smile, has at least one, "Airing," Hapax has "Purgatory," and laundry-pins, sleeves and stains pop up here and there)—I suspect all of these references in some way or another are an homage to Richard Wilbur's "Love Calls Us to the Things of This World," it's morning song of pulleys and clean linen and habits and difficult balance. My laundry, though, tends to also be the laundry that in theory one tries not to air—more argument than aubade.

It has been pointed out to me that a lot of my poems seem to stem from arguments and domestic conflict, at least as a starting point. Hesiod begins his Works and Days with the assertion that there are two goddesses named Strife, a good Strife, and a bad Strife. The bad one is associated with war and destruction, but the good Strife is competition. Poets hate poets and potters hate potters—but that comes from wanting to outdo one another in the making of beautiful things, and it results in trying harder. It has occurred to me that Strife in this sense is a kind of Muse. Maybe my muse is strife.

Pandora is an ambivalent figure in the Works and Days—the first woman, and a punishment to mankind (for Prometheus's stealing of fire), but also beautiful, gifted (her name basically means gifted), and the mother of mankind to come. Like the jar (it is Erasmus who first confuses it for or conflates it with a box), Pandora is made of clay. If she's a punishment (as "work" is also a punishment for the theft of fire), she's also a mixed blessing perhaps, another mouth to feed, but also a skillful craftswoman. When "Hope" remains in the jar (a womb-shaped vessel after all), it's unclear if that is a good or a bad thing. It's a bit of a Koan, but it is hard not to see this as potential energy.

Perhaps that is all overthinking in terms of this poem, which is one that happened relatively quickly. This poem came out of three aspects of my life at once—real frustration with a broken machine and a certain kind of uninspiring work, the tendency to look at that work through poetry, trying to make something out of that frustrated daily-ness, and simultaneously thinking through the problems of translation and interpretation.

Unusually for me, the poem is in a hexameter. Generally, I don't think hexameters work very well in English; they tend to be sluggish and break in the middle. (As Pope famously said "A needless Alexandrine ends the song, / That, like a wounded snake, drags its slow length along," neatly dismissing the alexandrine in an alexandrine.) But I ended up embracing the hexameters, with end-rhymes, as well as rhymes punctuating the middle at the caesura.

The decision to title the poem "Ajar" came rather late. It was true that the washing-machine door (of an upright machine) was wedged ajar and couldn't close, so that word was in the air. Puns sometimes get a bad rap ("the lowest form of wit"), but I think they have always been an essential part of poetry, that magic of a word hinging and doing two things at once. Why not risk it? The pun connected the machine door directly to Pandora and her jar. But the title also suddenly wrenched the machine of the poem open, and I realized I could just divide the lines up, a visual and metrical trick I had first encountered in certain poems by Cavafy. Why not? The pun and the visual spacing could I suppose be thought of as gimmicky, but they all came together (or pulled apart perhaps) at once, and seemed to be that crack that both let out the stewing evils and somehow kept hope inside. Strife, the Muse, seemed to approve.