In Their Own Words

Alina Pleskova on “Our People Don't Believe in Tears”

Our People Don’t Believe in Tears

For Gala Mukomolova

I pull the Death card &you go Know what this means? not unkindly.

Something crucial about living keeps grazing me by inches. No grip

on my future. As we say, nu i chto? As we say other times, & so what?

Our people toast relentlessly to health, don’t fall for anyone’s easy grin.

We learn guarded early. In certain company, I’m cowed. I hollow out,

for ease of relations. My parents never knew Marina loved Sophia until

they heard it on the radio, decades after the poet’s death. Things were

complicated then, they said. You couldn’t just live as yourself. At Riis

with you, tits out & facing heavenward, I regard my debts to our legion.

In every direction: bodies gleam, however they present. To be legible

is a release. Someone’s hairdye trails fuchsia wake across the water.

Someone chugs rum on the sandbar. Someone dares leather getup

in rippling heat. Everyone believes in disco. Bliss takes a day-sized bite.

We’re no longer there or then, & yet: Yelena Grigoryeva will be murdered

in St. Pete tomorrow. For living as herself & loudly. Tomorrow, we will

make blini from my babushka’s recipe & lament over our split culture.

Jokes cut with our first tongue, the one that tends toward withholding.

My parents never knew I loved . Occasionally, my mother asks

if therapy is working. Our people prefer their tea & humor darker.

Where were you when you first realized how many more of us exist?

I was here, waiting dimly for my undoing.

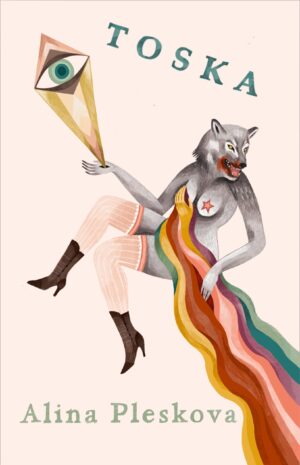

Reprinted from Toska (Deep Vellum, 2023) with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

On “Our People Don't Believe in Tears”

I’ve never gotten to a poem by thinking, “I should write a poem about X” and then writing it — I imagine that works best for people who have real discipline. But poets are, of course, variously preoccupied by specific things (we call them “concerns”) at various times in our lives, and sometimes the universe neatly stacks what you need to make a poem right in front of you. The associative leaping feels more like a path you trace in near-to-real time.

I was thinking about going to a rodeo for the first time on a recent trip to the American southwest, and how unsettling it was to be the target of strangers’ audible derision and disgust over holding hands and being affectionate with a woman in public – something I don’t think twice about in spaces I usually inhabit back home in Philly. To diffuse this with a dumb joke: it wasn’t my first rodeo in that sense, so why was it so jarring?

Shortly after that trip, my friend Gala brought me to Riis beach. Coming of age in the early aughts in a big, east coast city, I’ve taken queer spaces for granted in some ways, but visiting Riis for the first time made me giddy and sentimental. A queer beach! An unabashedly, smuttily, chaotically, gorgeously queer beach! It was remarkable.

Being there with Gala, a fellow queer, first-gen poet from the former Soviet Union, felt so special. More than most people I’m close to, she knows the tension of reconciling the fragmented aspects of one’s self – including a culture that one barely experienced firsthand, but is indelibly part of one’s identity. A culture that doesn’t even exist anymore, but was brought to another place in hastily gathered pieces. Some aspects I regard tenderly, like my babushka’s recipe for blinchiki, preserved in a recipe book from Moscow and transmitted via speakerphone the next morning by my mama while Gala and I hovered over the pan, halved onions in hand. Others not, like the same inherited cruelty that’s responsible for Yelena Grigoryeva’s fate, and the suffering of countless others.

Not long after, listening to a radio segment about Maria Tsvetaeva and Sophia Parnok’s love affair, my parents and I bantered about Tsvetaeva’s queerness. As Soviet Jews, they too knew about presenting as different versions of yourself, for your own wellbeing and survival. And the relief of being in spaces where, even if temporarily, you don’t have to do that. It was a bittersweet conversation, given what I left mostly unsaid.

My relative protection can be attributed to sheer dumb luck, but also geography, my appearance reading as queer or not at a given time, who I’m with. All of this renders me visible or not-visible, safe or unsafe, fragmented or whole. I thought about my joy and recognition at Riis with Gala – moments when my multitudinous selves get to coexist and hang out. May we all experience this at least long enough for unease to subside. Maybe even always.