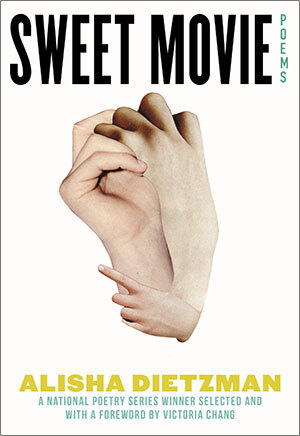

In Their Own Words

Alisha Dietzman on “stern—marlene dumas”

stern—marlene dumas

A necklace—that’s a joke. Photographic material reveals

marks, in this rendering rope-like.[1]

In appearance.

The image is not glossy but it is erotic in lieu of sexual.

The first time I heard a coyote I thought it was a murder.[2]

In A Few Howls Again Ulrike Meinhof resurrects

to tell us: my kind of violence made people nervous.[3]

I have been considering that I am not good for many years,

but lately it comes upon me, as we are come upon.

Naturally I am in every bar wondering about interior lives.

I like imagining tragedy, who doesn’t? A man confesses,

I can’t hear to what; it’s all tonal, like movies

where there are crows. One of my sisters calls daily

to say she wants to kill a woman.[4]

[1] But merely marks from the redacted rope (with which Ulrike Meinhof killed herself, or ).

[2] I am the kind of person who hears a coyote for the first time and thinks it is a murder.

I am the kind of person who hears a coyote for the first time.

[3] In another frame from Silvia Kolbowski’s A Few Howls Again, the text “she was unrealistic in the face of police brutality” floats above Meinhof’s body.

[4] Will you forgive me?

On "stern—marlene dumas"

Most of my poems exist in multiple spaces. This makes it difficult, I have been told, to discern the space, and ultimately because of this liminality, the poem.

This poem exists in at least two (primary) spaces:

1. Dundee, Scotland, in the middle of Covid. I spent all day writing my dissertation and taking long walks. I walked downhill from my apartment, to the Tay, where it was cold even in July. I walked uphill from my apartment to a vast Victorian-era park. The fourth chapter in my dissertation, originally titled Dead Girl(s), engages with Marlene Dumas. Dumas’ painting, Stern, features Ulrike Meinhof dead in her cell. Dumas used a photograph of Meinhof’s body from the magazine Stern. (The same photograph inspired Gerhard Richter’s triptych of Meinhof paintings.) In the painting, a mark from the rope with which Ulrike Meinhof hanged herself (or with which she was murdered; her cause of death remains contested) cuts a dark line around her neck. The image, in conversation with other work by Dumas, such as Broken White, based on a photograph by Nobuyoshi Araki, bears more than a passing resemblance to the Japanese photographer’s many images of bondage.

2. Ellensburg, Washington, in the summer of 2018. Most of this is about imagery: the bar, and its interior lives, in reality a place called the Frontier, the coyote, the sound of the coyote, waking me up in the middle of the night. I spent the summer of 2018 in Ellensburg, Washington because my husband panicked at the end of his PhD and wanted to briefly return to what he knew best: wildland firefighting. He worked two weeks on, two days off, and while he was gone, I tried to write a novel. I lived on watermelon and wine and didn’t know anyone. At night I’d get a little drunk and remember how my windows were so near to the ground. I’d leave them open anyway because it was too expensive to run the AC unit. I’d think, deliriously, about someone coming in and murdering me. I’ve never been happier in my life. The light was something you could not forget.

The way I approach space in Stern represents an intentional act of unlearning on my part. When I first started writing poetry, I was taught that the reader ideally experiences a consistent, congruent image-system; this grounds the reader in time and space, and guides toward a certain interpretation. Stern—a poem written in a damp Scottish flat about a painting of a dead West German Marxist, by a South African painter, suffused with the imagery of a cowboy town in central Washington—rejects this expectation. I wanted and want the poem to feel disorienting and more about a particular state, of uncertainty, maybe.

Stern (the poem) also features multiple spaces on the page: the body of the poem, and the poem’s footnotes. In an academic context, I’ve heard that the most important part of an essay often hides in the footnotes, which lurk under the surface. I think the most important line in Stern

hides in the footnotes.[1]

I am compelled by the quietness—maybe even the docility—of the footnote, and the way that it can both illuminate and simultaneously slyly obfuscate, or undercut. Footnotes speak under the breath of the main text. I wanted the back and forth between the argument as stated, on the surface, and the caveats, the clarifications, and the perhaps superfluous but beautiful details “buried” in the footnotes to help form a tense—uncertain— (poetic) object that subtly refuses the constraint of a single space.

[1] I think the most important line in Stern is found in footnote 4