In Their Own Words

Ama Codjoe on “Lotioning My Mother’s Back”

Lotioning My Mother’s Back

Because she lives alone and my hands reach

where hers can’t, she asks of me this favor.

It is narrow and soft, my mother’s back.

When I massage in small circles, my mother

circles her own mother, who is made

of whatever makes a shadow thin

and ungraspable. She wants to touch her.

The bones under my mother’s skin—ribcage,

scapula, spine—feel like sharp winter rain.

Between the clouds, I see a patch of sky, glimpse

my aging body: moles like a flicker

of paint, undersides of half-covered breasts,

patches of eczema my fingers soothe

with heavy cream. Is this what laying on of hands

means? Once my mother touched a garment

and said, full of an awe full of sadness,

She touched this, her skin was inside of this.

My mother’s back shines

like the hands I wipe on the towel’s face.

Weren’t miracles always beginning this way?

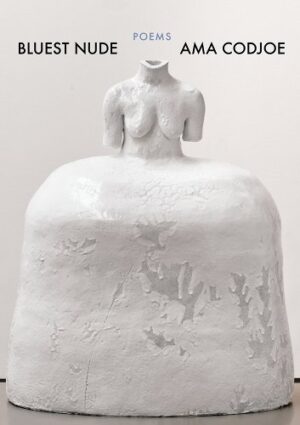

From Bluest Nude (Milkweed Editions, 2022). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On “Lotioning My Mother’s Back”

The poems in Bluest Nude brim with intimacy and grief, connection and rupture. In “Lotioning My Mother’s Back” the naked flesh of the speaker’s mother evokes a meditation on aging, loss, and the miracle of the present moment. Many poems in Bluest Nude, including this one, contain circles, echoes, and mirrors. I wrote “Lotioning My Mother’s Back” in order to consider times when I’ve encountered my mother’s physical and emotional nakedness.

When I look at my mother, I can’t help but observe her body as my

aging body. Already, my hair grays in the front like hers did when her hair was more pepper than salt; and, in the years since I wrote this poem, my skin has become more mole-flecked like hers. Also, when I study my mother, I see, without any effort, a portrait of my mother’s mother stretched like canvas across my mother’s skin. I find myself imposing memories of my grandmother onto my living mother’s face. What a haunting and beautiful dance the three of us make.

I know that to glimpse my mother’s aging body is a gift. To touch my mother’s living body is a precious, unreliable gift. The poem hopes to capture the sacredness of this mundane task given the ever-backdrop of our mortality. Finally then, the poem’s last stanzas are a retelling as well as a prediction of grief. Another echo.

What isn’t in the poem is the joy my mother gets from asking me this favor. She relishes the opportunity to have someone tend to her body in this way, and when she asks me, her voice carries a giddiness even though she is in pain. In her voice and in her asking is a knowingness of the answer. Yes. And, because she has given me the power to contribute to the temporary alleviation of her discomfort, I cherish this simple duty.