In Their Own Words

Anaïs Duplan on “The Room Is Not Cold & It Is Not Dark”

The Room Is Not Cold & It Is Not Dark

There is a girl in a red sequined dress

in the corner of my bedroom.

She has the most beautiful eyes I have ever feared.

I think I think I have never

had a dress with sequins like that.

She tilts her head & I am grateful. This is kind.

I know a tilted head

is a peace offering. It means, I don't want to kill you, I just

want to see you sideways. Or it means, I can't bear to look at you

right side up, god, the light when you're right side up, I can't.

I am still in bed. She is perfect. She doesn't ask me

to get up. Other girls might have asked

for food or a petting. No, she is quiet like a new bud, no,

she is quiet like a field of goldenrod at the end

of autumn & it's collapsing under its own weight. It could't

go on forever like that, the goldenrod, all gaudy & feathery

like that. No. She knows I am thinking about flowers. I can tell

because she is smiling. I know she loves me.

I am scared since love means losing your shoe & not knowing

where your shoe is for the longest time & never getting it back.

I ask if she knows what I mean, but I ask without saying it.

I mean I look at her & I know she knows what I mean.

She doesn't stop smiling but she looks at me right side up now

& I am scared. Her eyes are too much like rabbit's eyes.

No rabbit has ever looked at me but I know how it would feel.

It would feel like this. She holds out her hand, just the one, the left one,

& it is clenched but I know what's in it. I know she has a bird in there,

a little one. I know this because she wrinkles her nose.

The room is not cold & it is not dark.

The carpet is not soft & it is not dark. My bedsheets

do not fall onto the floor when I get up. Everything is ok,

I am glad she is here. Now we face each other & we are the same

height. She is five something & I am five something.

We have blonde hair & short arms.

She stands against my closet door

& I wonder if she put anything in there,

like a rabbit or like a gun. It's ok.

I want to get her something to eat from the kitchen

but she smiles so bright & I don't think I should leave.

It's rude to leave when someone's smiling. Her hand

is still there with the bird. I know it's for me, it's a gift,

but what's the best way to say I can't take your bird

because I'll lose it & where is my shoe.

Her skin is so white like the carpet & like our hair.

Please tilt your head. I don't say this but maybe I do

because she tilts her head again. She lets the bird drop

onto the floor & it isn't a bird, I was wrong.

It is a gun, a little gun. I don't want it. I say that.

Go to bed. I say that. You'll be tired in the morning.

Go to bed. She gets it, she gets

that I don't want her anymore but it's not because

I don't like her. I've never had a dress like that.

She's not mad. She leaves the way she came. Don't leave

the door open like that, close it.

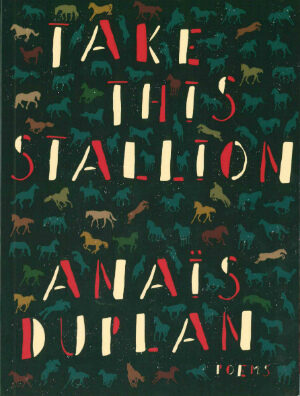

From Take This Stallion (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "The Room Is Not Cold & It Is Not Dark"

I've been embarrassed about this poem for a long time. One of the poems I considered pulling from Take This Stallion when my publisher, Joe Pan, and I were deliberating over the manuscript, "The Room is Not Cold" struck me as juvenile. In a sense, it is. It deals with an encounter with my child-self. Elsewhere in the collection, in a poem called "Hunger (Motivational State)," I write about an anxiety over losing my "childbody" and not feeling able to distinguish that inner child from my mother and father, "their postures." Here, the child-body makes its appearance in the first stanza, as the girl in the red sequined dress.

My fearfulness over the poem is the same fear expressed in the first stanza: "She has the most beautiful eyes I have ever feared." My sense now, on the other side of this fear—that is to say, having made peace with this inner self, and not only having made peace with it but having fallen in love with that self in a way that the speaker here attempts to avoid—is that the speaker is unwilling to claim the girl in sequined dress as her own. The speaker is in bed, in a room she wills unsuccessfully to be neither cold nor dark. The dark and cold room that the title of the poem denies speaks, in part, to childhood memories of visiting my father's house and finding myself in rooms I felt to be unfamiliar and therefore inhospitable. It is not an accident, either, that the adjectives "cold" (read: inhuman) and "dark" might also describe the kind of 'savage' figure that white Western culture has historically sought to obliterate, secretly identifying with it but always seeking to escape this identification so as to save some image of self which is "pure" and ideally human.

So, too, this poem deals with coming into blackness, by way of an identification with white features: "Her skin is so white like the carpet & like our hair." In some ways, this claiming of whiteness has been a necessary and vital component of my later loving claim of my blackness. (Nor do I much care for abstractions such as "whiteness" and "blackness" but they serve a purpose here I think the reader will intuit.) Black folk and women are inherently wonderful. At the time of writing this poem, though I may have felt this to be the case, I was certainly afraid to feel as much. To do so would have meant loving myself! Not only that but also, loving myself despite external and more sinister societal clues about how black folk and women ought to be 'felt-about.'

In the poem, the girl-in-dress holds either a bird or gun in hand. The speaker understands the girl's gift to signifiy a rite-of-passage, the 'gift' of one's gender assignment in society. (My tongue here is deeply in cheek.) This ritual gift brings only anxiety. "I know it's for me, it's a gift,/ but what's the best way to say I can't take your bird/ because I'll lose it & where is my shoe." The speaker fears she cannot acceptably perform or enact her femininity. She fears she'll "lose it"—either to have it stolen from her or by misplacing or neglecting it. Not to mention the speaker's fears about having no grounding in this world, no "shoe" to speak of. The shoe, which is caught in this metaphor about love as a loss and a perpetual subsequent searching for oneself, haunts the speaker in this deliberation over whether the child-self will present a masculine emblem, the gun, or a feminine emblem, the bird. It is to say, in 'choosing' an identity, the speaker fears the loss of her loved ones, and, more importantly, the loss of her-self.

I understand now that neither femininity nor blackness is a single kind of monster, though they are monsters, just as masculinity and whiteness are. All abstractions are monsters. In life, instead, we are sometimes afforded greater subtlety. This affording, of course, is not what happens at the end of the poem. Though intuiting their love for each other ("I can tell/ because she is smiling. I know she loves me"), the speaker and child-self are separated again at the end of the poem. The child-self retreats into the closet (perhaps an overly-wrought, by now, symbol for the deep interior) and the speaker is left to languish in bed--that is, in her own inability to act. It took, perhaps, my getting out of this 'bed' to see this poem for what it is: a beautiful, if fraught, self-encounter.