In Their Own Words

Cathy Linh Che on “I love the smell of napalm…”

I love the smell of napalm...

a golden shovel

Did I see napalm explode? All the time! Napalm

flames, their greasy fingers in the air. I wasn’t a son

drafted into the war, just a daughter to marry off. After Americans arrived, nothing

was left of my grandfather’s home. What else

do you expect when tanks roll in?

Translate the

word. Na Pom. Oh. Yes, the bombed world.

Today, I enter my garden, teeming with smells,

basil and lemongrass. Dragon fruit climbing over the trellis, reptile-like,

waxy and succulent. Guava that

swells under my watch. Once, a South Vietnamese soldier––I

knew him around the village––stumbled into our home. War takes everything we love.

He was shot by the Việt Cộng. I watched the

man bleed out into the sheets. It was the fresh smell

of death that got me. Flash forward: Scene of

myself on a film set. I was the Việt Cộng. I was the scenery. “Napalm”

explodes up. I heard bom, bom, bom shaking in

my fists. Couldn’t sleep last night. Who could sleep through a strafing, the

sounds echoing bom, bom, bom, from that day, into this morning.

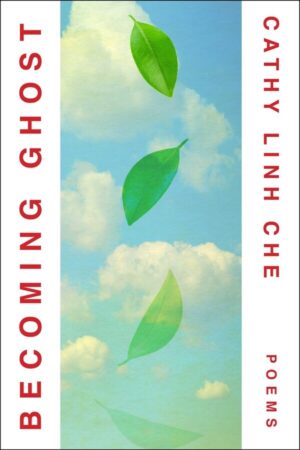

Reprinted from Becoming Ghost (Washington Square Press, 2025). Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On “I love the smell of napalm…”

This poem is the first in a series titled “I love the smell of napalm…” which uses the following lines for its golden shovel end words: “Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” Instead of allowing this very famous line to dominate the imagination of the Vietnam War, I wrote these golden shovel poems in my mother’s voice, my father’s voice, and my grandmother’s voice in order for their stories to be heard. I wanted to create a restorative and living archive.

“I love the smell of napalm” is one of the first poems that I wrote in my mother’s voice. It is based on the many conversations with my mother over the years, which were required to write Becoming Ghost, a poetry book that explores my parents’ experiences as Vietnam War refugees who were used as extras in Apocalypse Now. I wanted to find a way to center their voices which were sidelined in favor of a hyper-masculine American narrative of the Vietnam War. This led me to write poems in the voices of my family, “persona” poems or, perhaps, more accurate to my experience, “seance” poems. I say seance because the poems are drawn from their voices, but work through my body, experience, and English to communicate.

My first book Split was written from a single speaker’s voice––one that most closely mapped onto my own voice and experiences. In Split, I reclaimed my voice as an act of self-love and self-definition. Becoming Ghost is a love letter to me and my family, to our collective voices and all our complexities.

I love this poem. Sometimes, I cry when I read it, recalling what my mother had to live through because of the Vietnam War. I am also moved by my mother's marvelous ability to give life to plants. She’s an expert grower, having been raised on a farm in Vietnam. I think of her gardening as an antidote to the toxic napalm, a chemical “defoliant” used during the Vietnam war. Napalm’s purpose is to kill plant life so that the U.S. military and its allies can more easily maim and murder, and my mother’s purpose is to nurture plants and so that they can offer up their fruits to family and friends, feeding us all with their deliciousness.