In Their Own Words

Chen Chen on “The Cuckoo Cry”

The Cuckoo Cry

Lost the milk, spilled my marbles, our thoughts are fragile

says the Russian prof, & I try to gather, hold tender

both spilled & lost, my ugly diptych of spring,

every spring my windows open & ugly happens,

I try to hold it together, though maybe should let it go,

gush, let spring bark & heat rain from pit-stained

clouds, let the lark, no, the cuckoo cry.

Let spring say (the truth) I called my mother

a bitch. Said everyone in the neighborhood knew.

She had almost struck down my door, asking who

was on the phone, who, she had struck me,

called me names, forbidden me from talking

(WHO) on the phone, some boy wasn't it,

sick boy spreading his sick musky spring,

American spring, beastly goo of wrong wanting.

Spring says I told my mother she was living in

a dream, could never go back to the way things were.

& she said, Not even here? I can't say what I feel,

here, the one place I have in this stupid country,

I can't just be, rest, I have to fight, even at home?

Spring says it doesn't want to be personified,

wants to be forgotten. Doesn't want to be trigger

for memory. Spring says it & fall are retracting

their contractual smells & birds, their unlimited

catalogue of liminal spaces. Fall says, Stop

naming children after me. I say, People name

their kids Autumn, not Fall.

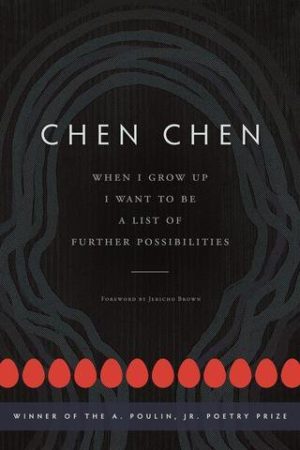

From When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions, 2017). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "The Cuckoo Cry"

I forget how sad some of my poems are because people tend to point out the humor. And I like making people laugh. Writing about this poem, though, made me see the sadness. This poem came a little after realizing I had all these poems about a confrontation between mother and teenage son, a rupture that occurs because of the son's growing sense that he is not, at least not fully, straight. Or, the rupture occurs because of the mother's inability to talk to the son about what he's going through. The son isn't able yet to articulate how he identifies, if it is an identity; he can barely use the word gay and indeed it feels strange to name his desires.

All he knows is that he likes looking at other boys. Or, he can't stop looking and he doesn't want to like looking. He has crushes. He likes their names. In this poem, he's started to talk to a boy who has similar likes. Maybe they like each other. Or, they like talking to someone who also isn't sure what to call this kind of liking. There's a state of suspended naming, an intimacy built on not naming, not yet.

But the mother insists that she has already named her child. Part of the son's name, in her view, is her child. How can her child keep his name if he is talking to other boys about strange likes and unnamable looks? How can her child be hers or a child, anymore?

Or, the mother wants to talk to the son, really talk to him. The mother likes telling the son about what she's going through, as an exhausted immigrant in a racist country. The son listens but doesn't always like listening. In this poem, he hates listening. He wants other stories. He wants some of his own really talking—to someone who gets it. The son gets a lot of what the mother tells him because he experiences a lot of similar racism and economic hardship. But the mother has no reference point for the son's experience of queerness. She knows the name gay but instead says sick. And the son replies, bitch. The rupture occurs because of what gets said. The estrangement grows because of what can't be said. Or, what can't be unsaid.

At the same time, the son is just a teenager. Still a child in some ways. Should he be judged harshly for saying a stupid thing? Who gets to judge? How do our memories judge us, prod us, dwell in us and in what we say now?

After writing this poem, I felt that perhaps I was writing a book of poems. I started to see how I had written several poems that revisited scenes—or maybe just one scene, finally—of this conflict between mother and son. These poems would form the core of my book. I came to see how I had an obsessive subject and how I had to keep finding ways into it—strange ways, scary ways. I didn't think I would write this poem. For a while, I was avoiding writing this book. I tried writing poems that were just funny. I wrote bad jokes, lineated. Good jokes, though, seem to come out of some true hurt. Or, they make room for the hurt to say something true.