In Their Own Words

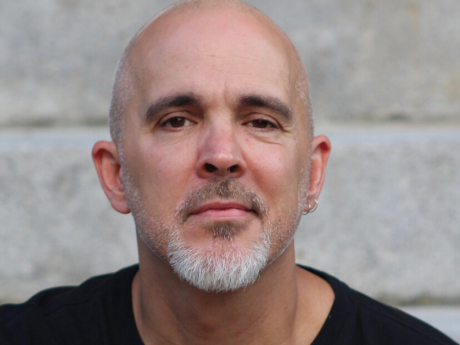

Ed Pavlić on “Someone’s Getting the Best, the Best, the Best of You . . .”

“Someone’s Getting the Best, the Best, the Best of You . . .”

—for Prince Rogers Nelson

Maybe it creased and held itself open

in the sky, a pearly seam tongue-traced across sunset

on a thigh? Your death has clung to me

unlike other deaths, chance web, a filmy

permanence I walked through a week, a month

a year ago. Death today speeds past

what it knows, media flung: fifty-five blown

in Lahore, how many, eighty-six,

burned in Dalori? One of three

found in the woods, friend of a friend,

down the block. Who can help us—

“Till way next Sunday?”—bring on the Crab

Nebula? Who’ll tell me when

that last one was mine? Didn’t know you.

Never dreamed of you.

I was a teenager in the early 80s.

My father was an absentee bricklayer.

My mother worked her way up

to telling me to take down

the poster of you I had in my room, nude

in the shower, with a question

in each eye and a gold cross on a long

chain. Your voice told me sex

was something very nearby, a slowly-er

rage that pulls us out into our bodies

and beyond ourselves. That was you

and Meli’sa Morgan did “Do Me, Baby” too.

Toe on the pedal say wah wah say

beyond “Controversy,” beyond sticks

and stones and black boys

and white girls whose scent, by then,

I’d contrived not to wash off in

the shower. That sacred means how it tastes

to hold someone else’s life in my hands,

in my mouth, that a saint is someone some

danger I don’t know who

tells me things no one around me

will say. I confess, as an adult, I’d sensed a ceiling

in the sound of your guitar,

I wondered if you’d begun to defend yourself

against something with it and if

so, what? I never asked myself about that. I let it be.

Call it technique, maybe privacy,

a ridge of invisible hairs along the edge

of your tongue, the visible shape

of wind across the lake. I think I know now

elevators must be called decelerators,

instead. I think I now know why

a lover might just need another

like a hole in your head. Did you hear

there’s a re-make of you

in the Sahel, did you know the Tuareg

have no word for “Purple,” so the film’s called

“Rain the Color of Blue With a

Little Red in It.” Let’s forget

the taste out your mouth you came in here with.

Don’t cry, scream: It doesn’t matter

if it matters! Lost in a tiny body that swallowed

a huge country trying to live

without a word for pain. You held a lot

of us together, man, together

in ways we’d been warned about by

careful people hell-bent on ensuring the silent shape

of our deaths, you pulled millions of us out

beyond our bodies and into one another. So now

what? I mean what’s now? Some ’nother numb new

tunnel to learn? Some Charlie Brown staring

down at his phone? Maybe now now can only mean

fifty-four and me blown, mean eighty-four and us burn—

Something now tastes like tin in the water,

now something speeds past but doesn’t go away.

And, a hero, well, they’re always tragic,

and soul and rock and roll and—well, made so

by we who watched you pass—when we could have closed

like one listening eye—like a wing of blue

wind with a little red in it, over a dune, like Minnetonka like

a sweet, swung-low ache, like down-slow rage on a sound stage moving

across the lake.

From Let It Be Broke (Four Way Books, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author and Four Way Books.

On “Someone’s Getting the Best, the Best, the Best of You . . .”

“Ok, but listen up,” says ML, played by Paul Benjamin, in Spike’s Lee’s classic 1989 film Do the Right Thing. He’s speaking to his two partners on the corner in front of a brick wall painted in bright, Godard-ian red. Reluctant to make what he sees across the street known to his friends, ML stalls, “I’m going to break it down.” ML continues to stare. He strains his vision out of the frame as if what’s plainly in view across the street is somehow far in the distance, opaque, inscrutable.

Growing impatient with ML and whatever else in the summer heat, much of it radiating at the three sweating men from the glowing red bricks behind them, Sweet Dick Willie, played incredibly by Robin Harris, implores his friend: “Let it be broke motherfucker.”

The phrase “Break it down” had always been around. The previous summer, Kris Parker had concluded "My Philosophy" talking about someone getting “broken down to his very last compound.” But, after Do the Right Thing, and also because within a year Robin Harris would be dead, the phrase always came into my memory, mind, and into my voice with some trace of Harris’s inflection: an urgent call to clarity.

Somewhere in the years before I began writing the poems in Let It Be Broke, Harris’s phrase had morphed into an aesthetic and moral challenge. Even before poems began to take shape, I could feel them already challenged to confront the obliquity of the lyric with a directness that nonetheless didn’t confuse simplicity with stupidity, succinctness with one-dimensionality. The challenge was to do the reverse: to make a direct address resonate complexly. Also, Martin Luther King Jr.’s challenge, from his Riverside address in April of 1967, that we not succumb to being “mesmerized by uncertainty” continued to chime in my mind. Clearly and dangerously, however, a wide array of things the world at large took for certain weren’t the answer. Certainty was violence, too.

The call to “let it be broke” from the streets of my adolescence and young adulthood, filtered through Harris’s loving and confrontational tone, became

the form in the major sequence in the book, “All Along It Was a Fever," a sixty-page response to the question: “What are you?” As it turned out, for me, in order to let that be broke some of our historical and social paradigms of seeing and feeling and knowing ourselves and each other had to be confronted, defied, broken.

“Let it be broke” was about disfigurement, disruption, it was a call to fracture and rupture; but above all it was a call to tell the truth. But, it’s hard to tell the truth in a culture addicted to lying about itself. The language we’re offered by the world is already laced in lies.

As I worked on these poems I found that the call to “let it be broke” applied to certain codes of poetry and to poems themselves. Like everything else in American life, poetry also lived in the shadow of the auction block, the American marketplace that works day and night to commodify, to turn truths into brand names. Relevance often becomes just a word printed on the flip-side of a price tag. Also in relation to the shame of a working-class background in the midst of layers of bourgeois convention, and of a racially non-binary person living in a system of racial apartheid, I began to hear the accepted demands placed upon poems and poetry—to impress, to amaze and to stagger and astonish—as calls to decorate my cage. So, in deeply intuitive places, and before I’d begun to write them, these poems had started to resist calls for shows of equivocal intelligence, for new inventions in syntax that excited surfaces but left deeper structures in place. As I worked I felt like I was doing things “good poems” don’t strive to do, maybe even things we’re told—often enough without being told—poems don’t and shouldn’t do.

But, as if being stirred with a long stick, I could also feel that thing, poetry, happening under the call to “let it be broke.” Early in the writing of these poems a comment by Bill Gunn in Kathleen Collins’s 1982 film Losing Ground

joined Robin Harris’s imperative in the writing. Discussing craft with his mentor who is a purely abstract painter, Gunn’s character Victor accepts: “I have a need to make specific references.” When I heard that line in the film I recognized it immediately. It made me conscious of what I’d already intuitively set out to do.

The poem “Someone’s Getting the Best, the Best, the Best of You. . .” gathers up all of these impulses and imperatives as well as any single poem in the collection. Dedicated to Prince Rogers Nelson, I began to write it months after his death on April 21, 2016. The title came to me in Prince’s voice from the stage of his halftime performance at the Super Bowl in 2007. No one will break it down quite like that again. And I’d never heard the song “Best of You,” which I learned later was by the Foo Fighters, a band unknown to me. Prince had made it new, he'd made it his and he'd made it ours. Whatever it meant before Prince took hold of it in the rain that night in Miami, and coming straight out of “All Along the Watchtower,” out of Dylan and Hendrix, what we

heard in that line was a protest against political stupefaction.

Deaths come at us so fast in the 21st century, algorithms shovel them at us day and night, from near and far. We develop a kind of terrifying psychological Teflon to deal with that; that slippery thing inevitably then becomes part of how we handle everything. But in the months following Prince’s death I noticed something different. His death was receding in time but it wasn’t going away along with everything else.

So I wrote “Someone’s Getting the Best. . .” to investigate why that was and to collect and trace the tethers connecting me to Prince, whom I’d never met nor—despite a few vexing close calls—had I ever seen him in person. Under the sound of Robin Harris, Kris Parker, and Bill Gunn’s calls, calls that resound in the voices of so many, voices near and far, here and gone, those tethers became the lattice upon which the poem grew.