In Their Own Words

Iain Haley Pollock on “Not on the sea, not on the sea”

Not on the sea, not on the sea

Half in the outbound drag of the tide,

half on the wet, glassy sand, his face

turned left and seaward, the boy

lies on his belly, as does my son

in his small bed when, as if a medic

gripping a red gear bag, I hurry

toward him, hoping the mask

of sleep no mask, holding

a forefinger above his lip

to feel on my skin the rise

and fall, the rise and fall

of his breath.

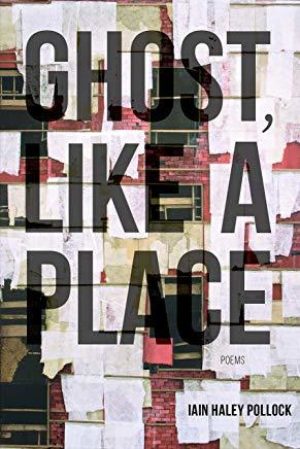

From Ghost, Like a Place (Alice James Books, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Not on the sea, not on the sea"

Commenting on another poem from my collection Ghost, like a Place, a reviewer recently and generously wrote that, "From that recognition of the constitutive activity of absence in life, the speaker learns his new ontology." Sounds great and part of me agrees, but that agreeable part of me is not the part that wrote the poem in question ("Indian & Colored Burial Ground") or any other poem in the book. As I generated them, I didn't think of poems in theoretical terms, in terms of "constitutive activity" and "ontology." My literary critical faculties might have kicked in and used such terms in later writing stages to justify or challenge the value of a poem, but these ideas did not factor into the conception or early revisions of my work. For instance, in "Indian & Colored Burial Ground," I was concerned with missing a recently dead uncle and trying to understand the implications of his (somewhat wayward) life and death.

This is all to roundaboutly say that "Not on the sea, not on the sea" was simple in origin and execution. I read Robert Mackey's The New York Times opinion piece on the drowning of Alan Kurdî, whom I am sure you will recall was a three-year-old boy drowned in the Mediterranean while his family crossed the sea to find refuge from Syria's still-ongoing violence. Mackey's article caused me to return to Nilüfer Demir's original photograph of Alan lying facedown on the Turkish coast. For all the terror that his family fled, for all the terror that must have been his last moments, I was struck by how surprisingly peaceful the boy looked as he lay prone in the sand. In fact, Alan looked as my first son did when I would check on Asa during his naps. Alan, of course, was not sleeping—he was dead—but the comparison between Alan and Asa, became indelible.

In connecting Alan lying dead with Asa lying asleep, I tried to relate the panic I felt when Asa napped for longer than usual with the anguish that I imagined responders who discovered Alan might have felt. I was struck that Alan's position "Half in outbound drag of the tide, / half on the wet, glassy sand," almost caught between sea and land, might give rise to the hope that he was caught between life and death and capable of being resuscitated. If I had been rushing toward Alan's body, I would have hoped that he were simply sleeping or recoverably unconscious. In considering the experience of responders, I hoped to commiserate indirectly with Alan's parents and the grief I imagined they felt. I've glimpsed the loss they've experienced only prospectively and briefly—in the too-long nap, in the ball chased into street as a car bears down—and even this hint tore me down and left me devastated.

Of course, I cannot fully commiserate with the Kurdîs: Asa lives and thrives. I daily know "the rise / and fall, the rise and fall / of this breath" and am supremely glad to know it. I sympathize with Alan's family but cannot contain the relief and joy I feel at Asa's continued life. This joy is not uncomplicated, and the shadow that dances in the background of this poem is: if these two boys are so similar, why does one live while the other died? Despite the many similarities between Alan and Asa—their ages, their appearance lying prone with eyes closed—the disparities between the two children most moved me. After the fact, my critical sense might have chalked this up as a response to global inequality, but in the moment of writing the poem, a Syrian Kurdish boy had washed ashore dead and my boy was alive, and the only correction I could conceive for this was to suggest that we see all children as our own children and treat them as such.