In Their Own Words

Jana Prikryl on “Benvenuto Tisi’s Vestal Virgin Claudia Quinta Pulling a Boat with the Statue of Cybele”

Benvenuto Tisi's Vestal Virgin Claudia Quinta Pulling a Boat with the Statue of Cybele

[a painting at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome]

A solid quarter

of it is blotted burnt umber

for the hull, a scripted curve, as if color

bricked over and over

could send a sailboat blowing from the canvas as matter.

Similar:

shipping the goddess from a backwater

then setting her up here.

And I'm the golden retriever.

Eyeballed from behind, female with yellow hair

contending with a hawser.

Manifestly unafraid to show my rear.

"Sip antiquity from my spot on the Tiber!"

Daylight buzzing like an amphitheater.

Not everyone is born to be a master.

He did sketch Michael roosting with his sword

on the grave of the Roman emperor

in perspectival miniature,

echo of the statue in the fore.

More on her later,

all the eunuchs and bees you can muster.

If you had to name the gesture

of the frontman with the beard

and frock of a Church Father

gaping at me from the future,

you could do worse than basta—hands perpendicular

to the ground, each white palm a semaphore,

head tilted halfway between concern

and something he won't declare.

To all the girls Bernini loved before

I'd say, caveat emptor.

The deathless ars

longa, vita brevis guys will have me clutch a carved

toy boat but this provincial follower

of Raphael goes for the ocean liner.

Reality's my kind of metaphor.

The heavens circulate with the times on the far

horizon and I don't have anywhere

to be except this unambiguous shore.

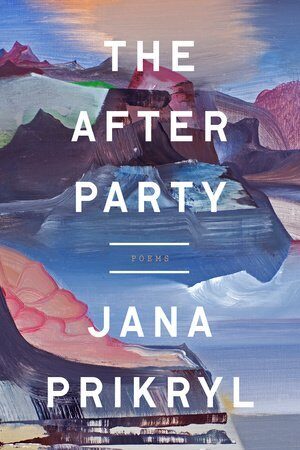

From The After Party (Tim Duggan Books, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted courtesy of the author.

On "Benvenuto Tisi's Vestal Virgin Claudia Quinta Pulling a Boat with the Statue of Cybele"

Visiting museums in Rome a few years ago, I was surprised by how much of the post-Renaissance art—because there was just such an amazing quantity of it—was bad. Piles of awful eighteenth-century portraits, lots of minor paintings from major periods. But seeing this kind of work was strangely stimulating (giving glimpses of creative activity you don't see at, say, the Metropolitan Museum), and when I came across Benvenuto Tisi's scene of an obscure classical episode I stopped short and stared at it for a long time and returned to it over several visits.

The painting shows Claudia Quinta, a Roman woman maligned by gossip, proving herself virtuous by single-handedly hauling a ship off a sandbar in the mouth of the Tiber; the ship contains a statue of Cybele, a goddess from Asia Minor, who will soon be adopted as a new Roman deity. Ovid mentions the episode in his long poem Fasti, which he wrote in exile in a futile attempt to impress the Emperor Augustus and return to Rome. Though the passage is brief, it's hard not to feel that Claudia is partly a stand-in for Ovid himself, who in writing this poem cataloging Rome's rituals is trying to prove his worthiness as a Roman citizen, his sense of belonging to this culture.

What seized me when I saw Tisi's picture was its literalism: painted almost as storybook illustration, its every detail is rendered doggedly and in the same rigid brushstrokes, as if to nail down as much of its meaning as can be conveyed without words. Did Tisi have doubts about the expressive power of his art form, or was this the only way he knew to paint? There's something very poignant to me about this kind of bad painting, which inadvertently makes formal insecurity part of its theme.

And the more I looked at it, the more I felt for Claudia Quinta, immortalized so ineptly by a male artist who automatically enjoyed a thousand more opportunities than his average female peer—a predicament that happens to apply to most Western art, at least the art made before the last few decades. I found myself compelled, for a long time afterward, to imagine Claudia's situation, both in her legend and in this painting. The poem grew out of those imaginings. Its formal traits—the monorhyme, the relentless declaratives, the indifferent line and stanza breaks—spring from my attempts to find linguistic counterparts to the severe, almost comical limitations of Benvenuto Tisi's painting style, which after all shape the way Claudia Quinta is able to present herself to us still.