In Their Own Words

Jennifer Kronovet on “The Future of Writing in English”

The Future of Writing in English

I

After being released from a concentration camp and becoming an exile in Shanghai, Charles K. Bliss invented a language of no sounds. A writing system of symbols to circumvent speech, its manipulations. Ideographic. Ideo. Idea. Ideal as the space between mind and page as silent.

In the future, English writing more and more becomes the opposite of this. Each word must be said aloud for it to appear on the screen. Seeing, without saying—that's the manipulation. From voice, which has become content the way sex is the subtext. The flesh of meaning.

English adopts a notational system of dots and dashes above and between words to approximate tone, to make the speaking silently talk. We can't trust them, the words, to be the mind behind. A dot. A dash. The speech within speech.

II

In 2013, a Canadian company released the program ToneCheck that screens emails for potentially conflict causing language. Post-meeting anger: alert. Late night reach/bite toward a lost lover: don't.

In Future English, the thread of feeling in each word has become an overt overture, a prioritized primal focal point. Words are color-coded according to an emotional template based on the smallest fluctuations of pulse and temperature in the tips of fingers. What do we encode into words with our bodies as we speak? There is technology for this. It's right there in red red red.

III

Dear A,

I just want to say. I have been. I think about. Now you know.

With a feeling,

Jenny

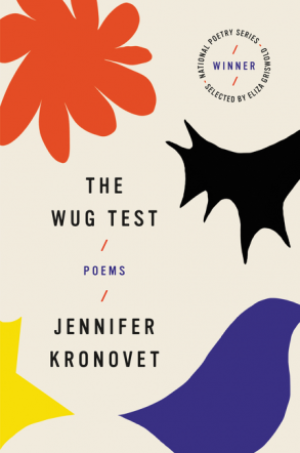

From The Wug Test (Ecco Books, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted courtesy of the author.

On “The Future of Writing in English”

"If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it."

—attributed to Joseph Goebbels

I picture Charles K. Bliss, the inventor of a language, listening to Goebbels's speeches over loudspeakers in Dachau and then in Buchenwald. He heard this: how Goebbels drew from beloved poems and phrases inside German to tell lies to make his dream of Germany true. But then I turn the picture in my brain off. No matter how many books I read about the camps, how many photos I see, I know that imagining myself completely inside that particular horror is a lie.

What could the German language be to a Jew after having listened to Goebbels? I am learning German now, and I listen to everything I can—commercials, news, songs, television, poetry—everything except Goebbels. For the time being, I want to hear him in English, at least until German is less foreign to me. German is foreign to me and isn't because it still reminds me of Yiddish, which I learned years ago to feel closer to a past I can't imagine.

I picture Bliss in Shanghai. It is the Shanghai I've been to because to imagine it differently than how I've seen it feels like a lie. I want to keep as close to Bliss as I can. He has fled to Shanghai, the war still on, to meet his wife who somehow managed his release from Buchenwald. Eventually they are put in the Jewish ghetto, a place I've been to see—there, Yiddish letters exist alongside Chinese characters—a rare alignment that mirrors my thoughts.

Bliss had the kind of brain I don't: he could look at Chinese characters and keep them inside his head without sound until he understood what they meant. He kept the patterns of Chinese working until they clicked into German. Of course, his understanding was simple. But even so, I need more than he did. I need to know the sound of a character in order to learn it. And then I need to flip between English and Mandarin until the Mandarin leaves English behind in my mind, if only for a moment. What exists in the distance between two languages? Walter Benjamin thought it was a kind of pure thought, but I wonder if that is where lies come from.

The other day I was talking to a man in Iowa who was born in Rwanda and grew up in Kenya. He speaks five languages and told me that he wished everyone in Africa just spoke English. "You go two hours away and you can't understand people," he said. Between languages, he thinks, is where war lives. Bliss said that same thing of his hometown, what was then the Austro-Hungarian city Czernowitz. There, he said, people "hated each other, mainly because they spoke and thought in a different language."

"Tell me something in Chinese," the Iowan from Africa asked me. I did. I asked him how he was doing in Mandarin. Then he said, "you seemed like an entirely different person when you said that." I asked him if he would be different if he grew up speaking English and not Swahili, and he dismissed the question: "does it matter?" It matters to me and so does his belief that it doesn't matter. I try to hold both of these ideas in my head as I move between languages: this movement is everything I know and is also a lie.

Bliss, inspired by Chinese, created a language he thought you couldn't lie in, or more, a language one couldn't manipulate, couldn't turn into propaganda. A language that could be understood by everyone. Blissymbolics: "Non-alphabetical Symbol Writing readable in all languages." I learned about Bliss in the terrific book In the Land of Invented Languages by Arika Okrent. I am drawn to the idea that a perfect language can be created the same way I am acutely aware of the folly of that dream. It isn't the words themselves, I know, that are lies. It is the distance between what the speaker knows and what the speaker says. That distance is not where war lives, I think, but something too insipid to have a name. Is it the fault of language that we can use it toward the better good or the worst evil?

Okrent tells the story of how Bliss's system was ignored until people found a use for it to help children who could not speak to communicate. And then, once people were finally using this perfect language, Bliss felt that it was being corrupted.

I've felt like this recently. That English is being corrupted. But it's more that a kind of empty space between world and speech is growing wider and in the space between is a country divided. How can we talk to one another?

Goebbels, in one of his jubilant speeches said, "Everyday language is not enough to express what we feel in this emotionally festive hour, to say what moves us so deeply." As a writer, I have also rejected "everyday language" while also rejecting the banal triteness of the phrases that make up the nothing that "everyday language" suggests. Instead of trying to lie, I'm trying to cut so deeply into language, to make it sit there, questioned and undone and yielding and transparent and new in its fragility so that it always shimmers as something that works on us, against us, and is a part of us. Poets are often not in the fact-game, but, I've come to see, facts aren't the opposite of lies. Questions are. Goebbels knew it.

Here is a poem with Bliss in it from The Wug Test, a book that tests, with the help of linguists I love, language itself to keep it exposed, to be in service of tearing apart how language can lie and can also be a way through toward a kind of truth—an unstable questioning, the kind that terrifies liars the most.