In Their Own Words

Jesse Nathan’s Eggtooth: Making It New

What Ruth May Have Wondered

by Jesse Nathan

Silence in the countryside gets so dense and so deep

it amasses body, untellable shape, heavy, larger

in its nothingness. On windless evenings

it would wrap around us like a vast comforter.

Your ears can ring from it,

it seems a witness

listening, swallowing itself.

And if your mood is gentle, it is the gentlest cradle.

And if you’re wheeling with fear of what might be,

it’s cousin to madness. Then again, later on

when we’d moved to the city, noises would heckle me

as I slept, a motorcycle’s bay

blocks away zap me awake—

or I’d lurch up to a siren’s catwail,

shuffle to a window to be amazed how few stars are there.

Starry-eyed love, old book I’m reading says, is flattering mischief.

When he and I met, I lobbed him a fat apple for

his true smile, his strawlikeness, his bearded unbelief.

I said I take my apples like onions,

diced or fried, and my onions

like apples, in hand, in smiles, raw—

and he says he likes raw, too—and then we’re talking

with the dead we miss most, and necking against a tree.

I savor his filthy wit. One reunion of his gawking

relatives, he deadpans on his way to the toilet Gonna be

right back, got a package to post

and I’m in stitches trying to keep my repose,

keep my coffee out of my nose.

Stitching we did by trading stories. His house

jacked by lightning, say, for the one about my father

who caught me dancing (in pants!) and swore my blouse

fitter for the street. Or how that machine swallowed my brother.

But now I get a creeping wonder

that all we have in common is some other

oceanic longing. That we’re each other’s plunder

or plain alibi. And, can he name his privilege? Shall I?

Why is it I’m in terms of him here? Where his projections read

and misread the thoughts inside my head. And in my eyes?

Why won’t he meet them when we’re fucking?

(I’ve read the natives in these parts

gauged your stature by how far

you could see, not how far you could fare.)

I know there’s places on this earth where night goes on for months.

I’m asking for a steadiness that defies possession.

A hand under my breast, he hoists me to his tongue

and tastes. Feels nice. But what’s not a matter of address?

One of us once said—I’m not sure

who—I’ll help you steer

if you’ll wake to tell me where.

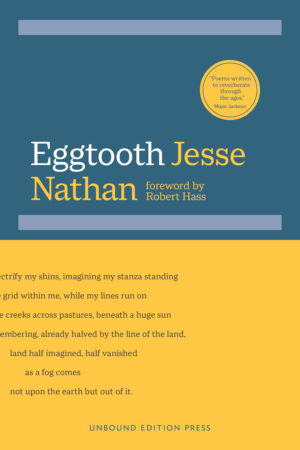

Reprinted from Eggtooth (Unbound Edtion Press, 2023). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Jesse Nathan’s Eggtooth: Making It New

by Robert Hass

How to speak about this brilliant and unexpected book? My impulse is mainly to point—look at this and look at this—and get out of the way. One of the pleasures of a new book of poems, especially a first book, is to turn to the first pages of it to see how the poet has gone about presenting themself. So here is the first stanza of the first poem in Jesse Nathan’s Eggtooth:

Young gray cat puddled under the boxwood,

only the eyes alert. Appressed to dirt. That hiss

the hiss of grasses hissing What should

What should. Blank road shimmers. On days like this,

my mind, you hardly

seem to be.

On days like these.

First of all, pure music: the rhyme on “alert” and “dirt,” and the delicious and unusual word “appressed” to get at the languor of the cat in the summer heat, and the way the s’s in “appressed” are picked up by the s’s in hiss, and the over-the-top repetition of “hiss,” “hiss,” and “hissing” and the way they end by rhyming with “this,” a word designed to put us in an immediate present. And the way the rhyme on “this” and “hiss” makes you notice that you have been reading a quatrain with an a-b-a-b rhyme scheme. And the way the quatrain devolves into a triplet rhyme on the “e” sound in “hardly” and “be” and “these.” And the way the “e” rhymes seem to transform the “this” of things into the “these” of things, changing a moment into days, into the languor of summer and the blank road’s shimmer.

My next thought was that this is gorgeous writing, and that, though there are in the emerging generation of American poets a considerable number of very interesting poets working from a range of aesthetic commitments, no one I can think of is writing quite like this. At times it reads like the packed and modulated music of early modernism, of—say—the young Hart Crane of White Buildings. And there are things I found myself charmed by—the poet’s address to his own mind, even as it seems to dwindle to nothing in the heat and the short-line rhymes. And who does triple rhymes in English in the twenty-first century? It’s the idiom of songwriters, Ira Gershwin and Cole Porter and Bob Dylan. It seems to belong to that kind of bravura playfulness. And I noticed and loved the fact that the only thing in the scene that isn’t immobilized is the cat’s eyes. They are “alert.” The poet’s mind may be going, but the cat’s isn’t. That’s why it’s under the boxwood hedge. It’s hunting. And, sure enough, three of the local bird species show up in the poem’s third and final stanza. Which led me to another thought, that the poem is so much about what it’s about—a place and a time, and also consciousness—that you hardly notice the way it’s written. It has fused its matter and manner entirely.

I’ll save the third stanza for your inspection, but to see a little more of what he’s doing in the poem, here is the middle stanza:

No, no. See that sidelong silver drum? That hiss’s a sigh

of the propane tank. Two o’clock. You can smell it.

Don’t breathe that sigh. The creek’s gone dry.

Summer as wide as this wildered sky, days like this.

My mind, you hardly

Seem to be.

Straw-frail, no breeze—

More music. This time abundant internal rhyme added to the end-rhyme, and it occurs, just as the subject of the poem, or at least its location, comes clear. A propane tank: we’re in a rural place, in fact, as we’ll find out as the book proceeds, in rural Kansas in the middle of the country in the summer heat. And this information comes up at the moment when the poet is correcting an impression. Doing that, revising the report on what is being seen—“Once again,” Wordsworth wrote, “I see these hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines / Of sportive wood run wild”—brings the reader to a peculiar intimacy with the speaker in a poem.

“Straw Refrain” is offered as a kind of opening note to the book. The first poem in the first section, “Dame’s Rocket” shifts gears stylistically. It’s a poem about a plant, in relatively short lines, a twenty-first century free verse poem in the twentieth-century manner of William Carlos Williams, the sentences disposed elegantly into phrases in the rhythm of speech, the diction the diction of spoken English—“they say,” “what’s left.” It’s the principal medium of American poetry for the last hundred years, and the subject tells us what “Straw Refrain” suggested. This is going to be a poetry of place:

Rising straight as canes

around the older farms, the hairy leaves,

little arms, the seed for jays,

the fragrance a marriage

of lilac and rose.

They say it came with the early whites

before escaping,

as ornaments may,

the farmyards and gardens

for what’s left of the prairie,

congregating sometimes in ditches

or among century hedgerows,

outliving towns

called Empire and Cicero.

Dame’s rocket is in the mustard family, with flowers like phlox. They like disturbed ground and they grow all over Kansas, and, something between a weed and a wildflower, as the poem says, they are not native to North America. They’re European, escaped from gardens. There is a lovely ecological and historical alertness throughout Nathan’s poems, and it’s evident here. Dame’s rocket. What a funny name, an English name from a time when rockets were fireworks and “dame” a dainty epithet from Mother Goose. And, he observes, this colonial has become a plant of ditches and hedgerows, outliving some of the towns to which the colonizers gave names full of classical resonance. There is something resonant, too, about the phrase “older farms.” Like “century hedgerows,” another European term, it calls up a past that is also called up by “what’s left of the prairie,” because Kansas had been a sea of deep-rooted prairie grasses before the plow tore it open to plant the grains that made people dream of towns named Empire. And the people who brought dame’s rocket also brought their culture, and that gets reflected in the metaphor of marriage and the way the plants are seen to congregate.

The next poem, “A Country Funeral” returns us to the rhymed seven-line stanza and introduces us to the culture of the place. Here is how it begins:

The breeze, quick-footed, skims the beards of wheat

trailing its hem over yellowing tassels

with a gliding so cruel for appearing so free

as it blows through a hog-tight bull-strong fascicle

of shelterbelt planted to revoke

its force and flow—

We’ve no polished phrases to recite, no

—our sung phrases reel on it, righten to a chord-plan—

—Abide with me, free us to grieve—

and I’m nine, taking mama’s hand …

So much to admire in this writing. If you want to be taken well inside this country, wheat-growing southcentral Kansas, the land, the weather, the crops, the radical simplicity of the old European protestant sects at their ritual of burying the dead, and fixing it in the form of a transmission to a child’s hand from the mother’s, it’s hard for me to see how you could do better, more magically than this. What won me on first reading was that “hog-tight bull-strong fascicle / of shelterbelt”—music I imagine Seamus Heaney would have loved, or Basil Bunting—and what amazed me was what came after, as if it were one of those haiku that seem to sum up entirely a certain view of life—“a gravedigger with no sleeves / smokes in the gravel lot / by his backhoe on a mat”—then managing to rhyme “lot” with “mat” and “thought” because the gravedigger, while the congregation sings their plain hymns of grief, is “hearing his own thought.”

The next poem—and then I will stop paging through the opening sequence—“Boy With Thorn” is a single stanza long, and acts out comically the evolutionary meditation on plants and people that has been introduced, reminding us at the same time that in the deepest parts of memory our connection to place is apt to be embedded in the memory of bee stings, scraped knees, allergies, and in this case the really vicious thorns on locust trees. Which is why to write about place in a particular way is, as Wordsworth observed, to write about childhood—

Wedged in my plantar fascia’s rivers

of tissue, the tip of a spike from the locust

tree—some long as a boning knife—whose

thorn evolved to ward off long gone

mammoths, and who’s

yet to realize

their absence.

—and remind us that some things rhyme and some things don’t. Which is captured in the way that the s sound in “who’s” and “realize” and “absence” sort of rhymes and sort of doesn’t. And this may be the point when some readers, mainly those with an interest in technique, figure out where Nathan’s stanza comes from. (He informs us later in the book.) It’s one of the stanza forms John Donne invented early in the seventeenth century, around the time the English began to colonize North America, for his book of songs and sonnets. Here’s the first stanza of his “The Good Morrow”:

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?

’Twas so, but this: all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

I will leave it to readers to identify what Nathan gets from this echo and borrowing. My sense is that it registers at the level of sound the way everything is like and not like everything else; it creates an ecosystem of echoic effects. Fascinating to see what he does with this stanza as a musical theme as he moves in the later part of the book from Kansas to San Francisco (as if it were a move from the prosody of Donne to the prosody of Kenneth Rexroth). “Between States,” one of the two long poems in the book, begins in the Donne stanza and evolves into something like the free verse of Ezra Pound’s Pisan Cantos as it tracks the history and ecology of middle Kansas—

and I’m imagining

these stinging nettles in my path

electrify my shins, imagining my stanza standing

for the grid within me, while my lines run on

like creeks across pastures, beneath a huge sun

of remembering, already halved by the line of the land,

land half imagined, half vanished

as a fog comes

not upon the earth but out of it.

It’s an ambulatory poem. Something like the landscape-surveying English poems of the seventeenth century, something like an Australian walkabout, and something like Hart Crane’s “Indiana,” it is an entirely memorable hymn and elegy to, and accounting for, his ancestors’ part in colonizing the prairie. I think it’s quite remarkable the way he does it. He introduces aboriginal America by thinking about wind:

describing a people who must’ve had scores of words for

zephyr, people who (say the translators) could sing, “My children,

when at first I liked the whites, my children, when at first

I liked the whites I gave them fruits, my children,”

a people whom the white government

sent surveyors to to establish a trail’s way

through these parts (my aunt used to sing

“When the prince wants an apple, he takes the tree …”)

and the envoy arrived in that grass sea

to wheedle the Osage and the Kaw,

offering them $800 and a few saddles

for a promise of permanent free passage. Local trapper

as translator. He the best

they could scare up, his Kaw sketchy at best, and I’m imagining

my relatives soon flooding in

with cabinet and poppyseed,

bonnet and springtooth, hope chest and hedgerow,

their book full of martyrs, dear as a mirror

and quilts made in the drunkard’s path

by hands that wouldn’t hold a drink, obsessed and kind

selectively, women and men enough of whom

must’ve believed when they were told to

hallucinate a past to quell a present, told

“These are the Gardens of the Desert, these / The unshorn

fields, boundless,” in blank

verse it was home to “a race, that long has

passed away” “in a forgotten language, and old tunes,” “all is

gone” though the actual act of emptying

was actually still happening

even as they set to plowing (that first time like plowing

a doormat, the sod rent open

with a sound like a zipper)

harrowing, reaping, shocking, threshing,

which is to say by 1846 the Kaw

were penned in reserves …

The quotations come from William Cullen Bryant’s poem of 1832, “The Prairies,” a quite beautiful amnesiac account of the great plains in the blank verse of his master Wordsworth. The poem sits near the beginning of most anthologies of American poetry.

(It’s interesting to think about the very different forms of Protestant sensibility in American poetry—Emily Dickinson working endless changes on the hymn stanza, Walt Whitman’s Quaker mother and his way with the rhythms of the King James, Wallace Stevens and the practical disposition of his Pennsylvania Dutch ancestors, Hilda Dolittle and her Moravian Brethren (very near to Anabaptist roots), or the pacifism of William Stafford, another Kansan, and the Church of the Brethren. It makes one reflect on the fact that the Anabaptist sects, like Jewish culture, had to be profoundly conservative to survive at all the centuries of persecution they had to endure, and conservative in a way that also made for maverick and radical traditions. This isn’t explicit in these poems except here and there—a relative counseling a Mennonite boy from one side of Turkey Creek that it’s best not to marry a Mennonite girl from the other side of the creek—but it is an undercurrent to the book’s themes of rooting and uprooting.)

Jesse Nathan was born in Berkeley, California. Both his parents are attorneys, who met in the 1970s working for Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers. His father is Jewish, from a little steel town north of Pittsburgh, his mother a Mennonite from Kansas. When he was a child, his parents, in part influenced like many in their generation by books like Wendell Berry’s The Unsettling of America and Wes Jackson’s New Roots for Agriculture, moved to his mother’s home territory and began farming organically for wheat, eventually also setting up a mediation practice rooted in principles of restorative justice. The move was a decision that gave the young Nathan the world with which Eggtooth is saturated.

Mennonite central Kansas: the Mennonites were one of several Anabaptist sects that emerged from the Protestant Reformation. Anabaptists, according to one historical account, “were the unwanted and unloved stepchild of the mainline reformers, all of whom disavowed responsibility for their unruly offspring.” Along with the Amish, the Hutterites, the Brethren, and a few other groups, they were the most troublesome to political authority. Adult baptism, nonviolence, a refusal to swear oaths, technological skepticism, community, simplicity—they found many ways to challenge state authority and they were persecuted relentlessly. One of the books that came with them from Europe was a seventeenth-century account of their collective suffering called The Martyrs’ Mirror. Some of the Mennonites of Kansas, at least Nathan’s part of Kansas, had their origins in Switzerland. But persecuted there, they moved east and set to farming in Ukraine, and farmed there for a century before they were told they were going to be subject to a military draft, and that was how German-speaking Swiss farmers from Russia (or the Russian Ukraine) ended up in Kansas.

Eggtooth

doesn’t tell us much about Mennonite theology or spiritual practice. There is a wonderfully odd description of a footwashing ceremony, but mostly the early poems are about, made out of, an intense, sensual sense of place. Nathan’s mother’s grandfather was the president of Bethel College, the Mennonite school that Nathan attended, and one of his Mennonite uncles was a prominent theologian. But Eggtooth, as its title implies, is a book about growing up, a book—as Wordsworth would have it—about the growth of a poet’s mind. There is the farm, and there is high school, self-consciousness—“There was a boy even stranger than I,” he writes in “Scouts”—sexual experimentation, along with the storms and spiderwebs. So the latter part of the book is, among other things, the narrative of the narrator’s leaving with a lover, who also belongs to the Mennonite world, to make a life together in the city. It’s also—in “Aubade Within Aubade” the figure is a minus tide at Ocean Beach in San Francisco—the story of the dissolution of that relationship, and the beginning of another. And it is thrilling to watch him move in and out of his intricate stanza and various kinds and shapes of free verse in the telling that brings him to the urban poet writing this book.

Another of the pleasures of a new book is to turn to the end to see where it has taken you or what the poet has managed by way of a summation. Nathan ends with “This Long Distance,” a poem in which the speaker, living now in the Sunset District, is on the phone with his parents:

And the son, not really sure what then to say,

says an iconic radio tower, from where he sits, presents

like a comb jelly. And they, who in his imagination

are in the dining room he knows well, hold up their phone, up against

the back window to let him hear

the call—so personal and clear—

of the train out there.

It is a perfect image of the moebius strip of desire: to be homesick for the sound that called you away from home.