In Their Own Words

Jive Poetic on “Trademarks”

Trademarks

The embargo split us before our parents were born

on opposite sides of a missile crisis. His grandfather lost English

on the way to Havana. I picked up Spanish, but it falls

under pressure. At the table after the lunch table

he finds a bed at the bottom of a beer bottle and runs from it

back to the family reunion: our grandparents were cousins

now they are dead

conversations that can't be reintroduced

because the translator is in the bathroom

or walking back

or far enough to see our native tongues are not indigenous

to our bodies, they are proofs of purchase replicating

on autopilot, auction-block fugitives pledging allegiance

to the branding iron, they are African voice boxes

crushed into blood diamonds bought and sold

on the black market. No matter how far from the plantation

my cousin and I still aren't free. We can't even speak

without a master of both present

to translate our trademarks.

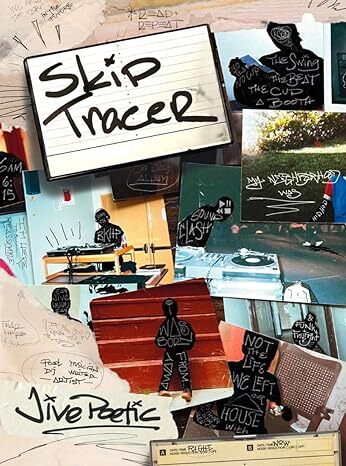

Reprinted from Skip Tracer (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2024) with the permission of the poet. All rights.

On “Trademarks”

Entry-level Spanish speakers can easily overestimate their abilities while living in New York City. They might have had fluent exes, friends, family members, teachers, or even a neighbor con una tía que tiene the best coquito y pastelillos in the building, and I’m no different. Telemundo is part of my digital cable package. I’m at the Dominican barbershop almost every week. I also hung out at Babalu Night Club with my boy Flaco, who, por un poquito de contexto, is half Puerto Rico, half Bronx, and all salsero. I wore suits at that spot to cover how my salsa comprehension and footwork didn’t speak the same language. I had a simple rule for when the trumpets and percussion started: no upper and lower body movements at the same time. I was all arms, shoulders, and facial expressions. This strategy estrategia let people see my efforts and offered room for them to help without getting their feet stepped on; this is also how I speak Spanish; my vocabulary vocabulario can flow in sentences, but the steps are, think in English first, translate second, and hope not to trip on dancefloors.

After Obama relaxed travel restrictions to Cuba, I started researching poems about my family’s journey to the United States. The process led me and Mahogany L. Browne to Havana. I felt Nuevo York enough to communicate when we landed, but Cuban Spanish in Cuba is different from bodega Spanish in Brooklyn. They used so many tantas palabras nuevas that made me worry my Sábado-Gigante Spanish was not fuerte enough to dance with my cousins. Our friend Christina Olivares, also vacationing on the island, agreed to translate my family reunion from the introductory phone call to the seafood restaurant where, just as I expected, no entendí mucho.

A fresh juice stand, a walk through a park, and a new restaurant later, Christina was overwhelmed from choreographing 70 años de mi historia familia into an interpretive dance performed into two languages. I tried to continue the conversation when she and Mahogany stepped away, but the background music was loud, and all I had were hand gestures and facial expressions. I regretted not paying more attention in Spanish classes or practicing harder at clubs with Flaco. Between selfies while waiting for Mahogany and Christina to return, it dawned on me: I was speculating on how much easier closing the distance between me and my cousin at this table would be had I learned an additional colonial language outside of English; it became disturbing when I decided the first thought should have been about how we would have communicated had our ancestors never been enslaved or colonized in the first place. I also thought about history being a story, language being culture, and how colonial syntax was a straining filter; I spoke, thought, and experienced the world in my colonizer’s terms, on my colonizer’s terms. Feeling locked to the past this way is painful and exhausting beyond the political, mental, and social struggles, as some people still think I’m hallucinating leg irons holding me back because our relationship to the Americas is different.

“Trademarks,” first published in Skip Tracer, recounts this Cuban trip while investigating objects that colonized bodies retained through European conquest to the modern-day exploitation and oppression of Africa and its diasporic descendants. It engages colonial languages as flags, brandings, and generational scars. It also expresses sorrow over ancestors and ancestorial memories lost in translation. “Trade” in the title considers the reduction of human life to a stolen item purchasable by the highest bidder, while “marks” signifies remaining traces of those experiences in contemporary life. In title and construction, “Trademarks” imagines inherited trauma as intellectual property of colonizers and enslavers who created it from their cruelty, conditioned it into psyches, and sold it as accessories to bodies on auction blocks. Another collective ponderance in the poem is freedom as a paradox in lives confined to and by colonial linguistics that once held them in bondage; it explores this by realizing the potential perpetuity of colonial subjugation when the subjugated spend futures solely communicating, sharing traditions, resisting, expressing identity, experiencing love, and preserving history through the tongues imposed upon them.