In Their Own Words

Kathryn Cowles on “Boat Tour”

Boat Tour

You will see to your left the new port

you will see to your right the old,

l’obelisque, to the left the clocktower,

only remaining piece of—

bombed by the Germans when they left,

now a great distribution center for fruit

all the way from Africa,

and the gulls on the roof scare

all at once, middle of the night,

all up in the air and yelling

their human yells, the fruit,

the stars, the war memorials in

three different languages,

bombed par Allemandes in 1944,

the waves are slight, very slight,

the water molecules, I am told,

stay in the same vertical trajectory

though they appear almost to be moving forward.

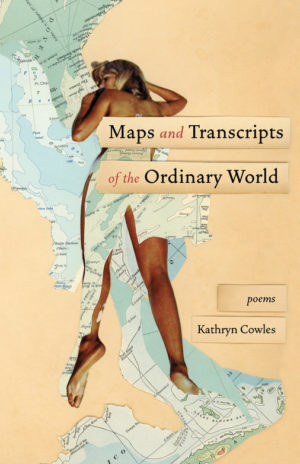

From Maps and Transcripts of the Ordinary World (Milkweed, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On "Boat Tour"

I like to write in unfamiliar places, to wrap myself in unfamiliarity, to fall for a place in the writing of it, to catch a tiny actual shred of it in language on the page if I can, like a verbal photo album, a pressed flower made out of words. For me, unfamiliarity is generative. It makes my eye pay new attention.

When I was in school, I had little money, but I found ways to live and write somewhere unfamiliar nearly every summer. One summer I was awarded a tiny travel stipend and went to live on an island in the Cyclades. I remember reading the Iliad’s gigantic catalogue of ships while looking at an actual Greek shore that couldn’t possibly fit them all. And writing and writing, trying to get the water, the real boats on the actual shore, to stick to my page. Another summer my partner and I advertised ourselves on Craigslist as two poets and a very nice dog willing to work hard in exchange for living in a beautiful place in nowhere Montana. We ended up in our now-dear-friend-but-then-stranger Sue’s bunkhouse, which had no running water, staying for free in exchange for feeding her animals and watering her lawn and mountain-flower beds when she was away. I remember sitting on rockers on the windy bunkhouse porch, wrapped in bright wool blankets and surrounded by dogs, writing and writing and writing, trying to get it all down before we had to leave.

A few summers later, we went to live on the second story of an ancient rowhouse in a small fishing village in southern France on the border with Spain that we found by poring over the local newspaper’s housing listings with our scattered French. The first night we were there was a town holiday, with fireworks right outside our windows. We had a view of the port from our living room. We left the windows open at night with netted curtains to discourage the bugs. We pulled the shudders in the morning to try to keep the cool night air in as long as possible. I would sit behind the shutters and watch boats go by through the painted slats and could, on quiet days, hear sounds echoed far across the surface of the water. I could hear the birds on the roofs of buildings on the other side of the harbor. I could hear music from the outdoor restaurants at the port. And I could hear the drone of tourist-boat captains talking into microphones to passengers while putt-putting past. I would sit every morning and listen and watch and write.

Writing unfamiliar things sometimes requires a new kind of speech for me. In my second book, Maps and Transcripts of the Ordinary World, a number of the poems veer away from the traditionally poetic into forms that feel initially almost anti-poetic—channeling quotidian documents like maps, recipes, contracts, guidebooks, dictionary definitions. When I started writing the poem “Boat Tour,” I imagined myself to be channeling the boat-tour captains outside my window as they described the history-drenched landscape in multiple languages to tourist passengers. But as is so often the case, the poem had something else in mind that was better than what I wanted to do. Instead of the captains, the poem started channeling the water itself, the waves, which I was fascinated to learn don’t actually move forward. They push energy forward, to be sure, but the actual water droplets mostly just move up and down, which is why a boat on the waves doesn’t get pushed right to shore but instead bobs and drifts. The waves in the poem start out more felt than seen, manifested mostly in the lineation, in the stacked phrases that bob between their commas, “the fruit, / the stars, the war memorials in / three different languages, / bombed par Allemandes in 1944.” Indeed, until the waves appeared directly at the end of the poem, I didn’t even realize they were there, but they were always somehow at the heart of the experience. Listening to a captain give a boat tour from my window in the ancient rowhouse, what registered was not the language of the tour, its content, switching between French and English, but the waves themselves, fragmenting the language, the drag and chop that happens to sound as it travels over water. But I was not describing the waves so much as writing in the form of them, taking on their rhythm and cadence, invoking not their literal shape but their feel.

I do this elsewhere in the book, invoking things by channeling them formally. In a prose poem called “Three hours in a rocking chair outside the blue-roofed bunkhouse in the wind,” the wind gusts its way physically through the otherwise-unlineated lines. You can’t see wind in a landscape, but you can see its evidences. You can see the huge Montana clouds from the bunkhouse porch move overhead toward the huge mountains so fast that the mountains themselves appear to be moving, which feels dizzying the way it is dizzying to lie on the ground in a snowstorm and look up. And you can see how the wind blows a whole dog over, even if you can’t see the wind itself. So to catch wind on my page, I had to talk about clouds and mountains and the dog and let the wind gust through my poem of its own volition and disrupt the form of my sentences. And to catch the sound-fragmenting waves at the heart of “Boat tour,” I had to try to take the form of waves, to snag some original shred of them and stick it to the page.

In truth, the world never really sticks to a page. A lot of the poetry I love best takes on wild impossible tasks, tries to say something unsayable, to transcribe something wild into letters, and fails. Jack Spicer writes in After Lorca, “I would like to make poems out of real objects . . . I would like the moon in my poems to be a real moon, one which could be suddenly covered with a cloud that has nothing to do with the poem.” But in the end, the page is not the thing it invokes. Even a world-sized map in Borges cannot be the same as the world. The good news is the world doesn’t seem to mind one way or another. It keeps on worlding either way. As so the wind poem ends, “I have tried to write it down. The ordinary world. When I did, and when I didn’t, it was always still there.”