In Their Own Words

Kazim Ali on “The Voice of Sheila Chandra”

from “The Voice of Sheila Chandra”

Breaks is constant was like

The river light on the river

Riven that remained a rift

An old rill that sounded

She merged with the vibe

Ration of the drum a hum a

Home womb and um

She OM moaned in the loam

Dark earth come Sheila

Dame ocean dome this poem

Roam to tome tomb foam

Original fountain that fed

My mom Zam-zam when I

Was born

*

Who can in syllables like

Sheila Chandra moan us

Covered in a blanket of sound

This like clouds bank of stars

Keeping us from eternity

Which under the blanket seen

Like Sanjay a dancer who I

Somehow look like was mistook

For three times in one day

twenty years ago but the story

still resounds some woman

at a festival saw him perform

swore I was he I said I wasn’t she

Did not believe

*

Me brass bowl soul swindle

Through years no identity theft

I want to move like that off the axis

Of the spine into where and where

Sanjay said I am not him and what

Does all this have to do with the voice

Of Sheila Chandra her having lost

Having now no longer sound

Now a constant striking into chaos

That note that flickers through

In abstraction one is one or zero

And confused the ear does not

Focus neither opens nor closes

Always is

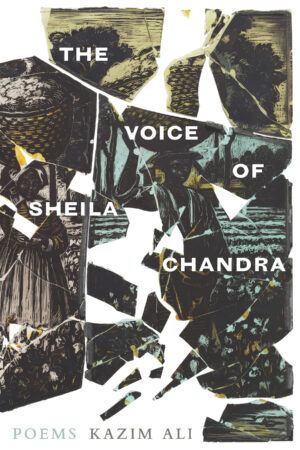

From The Voice of Sheila Chandra (Alice James Books, 2020). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On “The Voice of Sheila Chandra”

One day in New York City, about twenty years ago now, I was mistaken three times on the same day for a man I had never met. It happens in my life, every now and then, but that first time, it was specific: there was a festival of South Asian dance happening, and there was a dancer there who bore some kind of strong resemblance to me. One person recognized me on the street, another woman in the subway, and finally sitting down to dinner at Baluchi’s in the West Village, the waitress exclaimed in delight when she saw me. These are people who saw me up close, who knew the other man, who had seen not just his face but his body as it moved. The waitress wouldn’t believe my refusals. She insisted I was Sanjay.

When I moved from New York City up the river into the Hudson Valley at the end of August 2001, I felt my magnetic pole had shifted. When, thirteen days later, the New York City skyline underwent revision, I felt doubly or triply so shifted. In a new place and unheard and in times unheard of. The music of Sheila Chandra came into my life, primarily in the form of her drones and her konnakol—an Indian vocal style meant to imitate patterns of percussion. The singer—or dancer—often uses it to communicate to the drummer what pattern they wish to be used, but Sheila sang konnakol as a vocal expression.

If Judith Butler is right, and we become real when we are seen, then I am as much Sanjay as Kazim. I have tried over the years to locate him. “Sanjay” + “Indian Classical Dance” + “Philadelphia”—one of his fans mentioned to me he was from that city—has not, over the years, yielded his identity. Sheila Chandra too has undergone revision: suffering from a neurological ailment called burning mouth syndrome, which has no known cause nor treatment, Sheila can use her voice only sparingly and for limited periods of time. She cannot sing any longer.

I found in the sonnet shape in which to approach unheard of times, to talk about the slip of identity between person and person, to grapple with social, psychic and planetary crises. My sonnets proceed from Berrigan’s lineage more than Shakespeare’s, I imagine. They follow Wanda Coleman, and are grateful to innovations by Terrance Hayes, Harmony Holiday, Nick Demske, Ben Lerner. These sonnets though slip between Englishes, they have not one but multiple turns, and they use enjambment and mid-line unmarked caesurae to heighten a disconnect within. Their rhythms lie halfway between Urdu prosody and the beats of konnakol.

The central section of my new book is the title poem—either a single poem comprised of forty sonnet-stanzas or else a forty-sonnet sequence. The difference between the two seems meaningful and irrelevant at the same time. The voice inside breaks, the person inside is undone, yes, sure, but what I want to know is what happens to the voice after it breaks? How does the person undone find a way to go on? As for Sanjay: I hope he finds this. I hope he knows I’m thinking about him.