In Their Own Words

Laura Villareal on “Baby Teeth”

Baby Teeth

some afternoons music sways like a broken screen door

in a distant part of a house I was never a god in. it’s flooded

with marigold light & it makes sense that my milk

teeth have been traded to deep south spiritualists.

they say I was born fanged & feathered like

no child from heaven should be. a miracle

that when I lost those teeth I became human.

my feathers burned one by one each year of my life.

I’m tired of the way my mouth fills with guava

seeds like infant pearls after. give me blood

from pomegranates. I demand tears

in every screen door in the south until

they fall off their hinges or every onyx tooth

is planted in the ground around my body. wait.

let a song come first from a black storm rolling

over the still sorghum fields. I am nothing

if not determined to re-create myself as a god.

so let the birds steal my teeth from the ground

& hide them in their babies’ open beaks.

listen for the heavy stillness before the rain

& know I am waiting to become whole again.

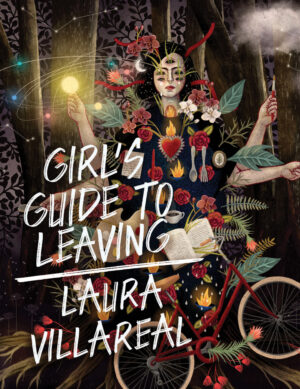

“Baby Teeth” was first published with Palette Poetry. From Girl's Guide to Leaving by Laura Villareal. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2022 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

On “Baby Teeth”

Often I liken writing poetry to putting a bucket down a well and hoping to bring up water. Sometimes the well is dry. Sometimes the pail overflows. When I sit down to write, I don’t know what will come up but I always hope for a surprise. I typically begin with a line that’s been bouncing around in my head and build from there. The images that fill my poems are gathered over time as I observe and engage with the world. Writing “Baby Teeth” wasn’t like that. The way it arrived was unlike anything I’ve experienced before. I was sitting at my favorite coffeeshop working (scrolling social media more than likely) when the words arrived, “some afternoons music sways like a broken screen door / in a distant part of a house I was never a god in.” It gave me goosebumps. It felt as though a voice was being channeled through me. I didn’t recognize the voice as my own and I still don’t even now as I read the poem aloud. So, I did what any poet would do and wrote the words down. Then I kept listening. A lot of times poems arrive when I’m not ready or able to receive them, but the voice of this poem demanded that I listen. I wrote until the voice finished saying what it needed to say. Even now I feel a bit spooked by the way this poem arrived fully intact. Poets, if words arrive—if a voice announces itself to you—then you must listen.