In Their Own Words

Lynn Melnick's “Town & Country”

Town & Country

When my friends were dying

back in the city, I was pretty damn healthy

out in the country, sitting on the taut taupe leather

of the passenger side, always the passenger side.

I liked to look out the cold car window

hoping the sun wouldn't rise

above that shitty yellow house

where food burned most every night

where mites ate the grain

where a mouse found its way

into the refrigerator and died

where it wasn't even an allegory

to say a snake bit my ring finger. It was supposed to be

restorative, refreshing. It was supposed to be

more wholesome.

A lot of men died that summer

but it's you I want to tell

that I wish you had done what you wanted to

back in one of our city's fine high rises

before you forgot yourself and before I

weighed more than you. I wish you had jumped

from your balcony down

to that courtyard cliché

and either broke or drowned or emerged

triumphant, glittering like the rainbow

you pointed out to me at a gas station

in Santa Monica, born from the grease stains

on the asphalt as you were pulling away.

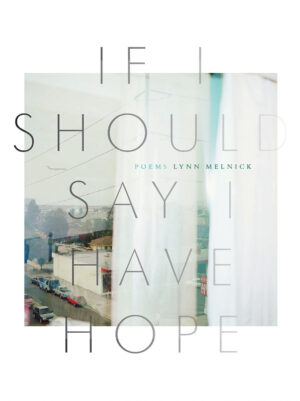

"Town & Country" from If I Should Say I Have Hope (YesYes Books, 2012). Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Town & Country"

When I was finishing up my book, my editor suggested I write a few new poems for the final section, poems that would perhaps move closer toward the idea of hope that sits in the book's title. This is one of three poems I wrote in that frenzied couple of weeks (I've never written so quickly in my life!) and, like most of my poems, I don't really know how it came to move from my head to the page to making any kind of sense. I guess I was trying to think of more hopeful things, within the idea of California, within my experiences there in the 1980's and early 1990's, which is much of where my book lives.

The first place my head went was to this house I lived in for a couple of years in Santa Cruz, when I was 18 and 19, and the very dark spaces I found myself in during those years. So that's the beginning of the poem.

Mites did eat the grain (well, the rolled oats or whatever, anyway), a dead mouse did appear in our fridge, and a snake really did bite my finger. Country living (well, city-of-50,000 living) failed to seduce me.

But I also can't think about those years without thinking of my friends, Tyree and John, who died of AIDS-related illnesses back in my hometown of Los Angeles, the year after I left for Santa Cruz.

Tyree grew up on a farm in the Deep South. He loved Dolly Parton as much as I do. He always wore red. He left his small county for the first time at the age of 21 to move to LA. He got off the train so innocent that he had his bag stolen by a crooked cab driver at the station within minutes of his arrival.

I tried to get that into the poem but it didn't fit. I tried to get in that the last time I kissed Tyree at the hospital—he always, always kissed me, kissed everyone he adored, directly on the mouth—he said, "you can't do that anymore." He weighed maybe 100 pounds. John, his lover, had already died that summer, at 23 years old, in a different hospital, near his parents' home in Long Beach.

When Tyree was first diagnosed, about a month after John was diagnosed, he got very drunk and threated to jump off his balcony into the gloomy little pool in his building's courtyard. "If I make it, I make it, if I don't, I make it anyway," he said. I wrote that down on my arm, pressing so hard with the ballpoint pen that I later had terrible welts. I was a stupid kid.

But I didn't want to end the poem with jumping. I was trying to write a hopeful poem, the poem where Tyree didn't die at age 28, all alone in a hospital room.

I thought about my life in Santa Cruz, which always seemed cold, which always seemed to take place under someone else's control, which was always in a certain car, hopelessly trapped by a thousand wrong decisions. And then I thought about being in John's giant blue car the month before I left the city, with Tyree up front next to his love and me in the back, lounging and smoking, and laughing. I thought of Tyree yelling "Stop the car!" and John hitting the brakes so suddenly that I went flying toward the front. Tyree caught my wrist and pulled me onto his lap so I could see the rainbow on the pavement, and, never mind all the pain that came after, there was hope in that moment—or if not hope exactly, then at least there was evidence that we still hadn't given up looking for beauty, no matter how silly or sideways. And sometimes we actually found it.

So I guess what all of this adds up to in terms of how the poem was written is that I had about a novel's worth of feelings and ideas and stories from those two years, and about those locations and people, but then I just had to sort of figure out what felt best for the poem and whittle it down into a few main ideas and a lot of small images that supported those ideas. I wanted to write about hope but I also wanted to write about how AIDS killed my friends and I wanted to write about loneliness, and it all came together in this one way, even though if I were to shake it all up again it might have landed somewhere else entirely.