In Their Own Words

Pauline Fan on Kulleh Grasi

Duri di Hujung Bibirmu / A Thorn at the Edge of Your Lips

Keresahan adalah lagu

sejambak bunga terbaring lesu di kelakianmu

epitaph terpadam di dinding

kaurenung kenangan

bercawat hitam di kerusi kaki.

Berjuta-juta batu

aku rakamkan sebungkus ludahan

kautukar menjadi haruman burak

camar ketawa bersindir

mabok di dalam kemaluan.

Peta masa berputar

bibirmu berduri

akei asi kui

takkan sembuh dijilat ketika.

Disquiet is a song,

a spray of flowers lying listless at your manhood,

an epitaph erased from the wall.

Sheathed in black loincloth

at the chair-feet, you sit and remember.

Millions of miles:

I chronicle a sachet of spit

that you transform into the scent of burak rice wine;

the dove laughs, mocking,

drunk in shame.

The map of time rotates.

Your lips are thorny:

akei asi kui

the lapping of time won’t heal it.

Translated by Pauline Fan

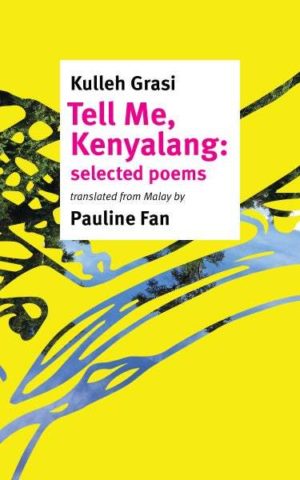

From Tell Me, Kenyalang (Circumference Books, 2019). Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.

On an excerpt from "Kulleh Grasi’s Entangled Universe"

The world Kulleh Grasi evokes in his poetry is both present and absent—it is seen and longed for, remembered and forgotten. It is the real and reimagined world of the poet’s homeland, Sarawak, the Malaysian state that stretches along the northwest coast of Borneo. Grasi’s Sarawak is a place where all things are "narrated, alive"—where Iban ensera tales, the call of omen birds, the drone of primetime news, and the roar of bulldozers coexist in perpetual oscillation between polyphony and dissonance. Here, the poet listens to the language of rivers and stones, to the leopard’s footsteps, and the thoughts of fishermen. He writes: "Every stitch in the net / is a tongue."

Sarawak is home to a diverse population of indigenous communities, totalling over forty sub-ethnic groups, broadly categorized as Dayak—including Iban (Sarawak’s largest ethnic group, also known as Sea Dayak) and Bidayuh (also known as Land Dayak)—and Orang Ulu (Upriver People), encompassing 27 tribes including the Kayan, Kelabit, Kenyah, and Penan. Despite decades of unbridled logging and deforestation, the image of Sarawak as a tropical paradise of indigenous tribes and lush rainforest persists in the popular imagination of Malaysians and foreigners, many of whom view it as an exotic destination for holiday escapades. Once nicknamed "Land of the Headhunters" by British colonial officers, adventurers, and orientalists who encountered the old headhunting tradition of Iban warriors, Sarawak is affectionately referred to by locals as Bumi Kenyalang, "Land of the Hornbills," the majestic bird that is a shared cultural symbol among the people of Sarawak and adorns the official state emblem.

In world literature, Sarawak was for a long time known as the land of the "White Rajah" James Brooke, the first British "ruler" of Sarawak who was portrayed as a villain in Emilio Salgari’s 19th century Sandokan swashbuckler pirate series, and who was one of Joseph Conrad’s main inspirations for the titular character of his novel, Lord Jim. Less known to the literary world are the intricate oral traditions and material culture of the indigenous people of Sarawak—storytelling, ceremonial songs, ritual incantations, pua kumbu dream weaving, traditional hand-tapped tattooing—in which their complex worldviews and values are embodied and expressed. While representations of Sarawak continue to be shaped by the often incongruous accounts of outsiders and locals, the power of the outsider’s gaze in defining Sarawak is gradually diminishing as indigenous communities assert their local knowledge and ways of telling, in traditional and new forms.

Grasi’s poetry is a new way of telling. It deliberately roots itself in the power of orality, inscribing the transient immediacy of utterance into a palimpsest of language and meaning. It subverts the persistence of literary tropes that portray indigenous people as noble savages, by turns oppressed and exalted by a doomed humanity. Drawing potent symbolism and structure from indigenous oral traditions, Grasi’s poetry does not seek to rescue, reclaim, or recast. Instead, it urges a rethinking of representations of "the indigenous," resisting sentimentalized notions of cultural identity as well as reductive binaries of tradition vs. modernity. By choosing Malay, the national language of his country, as his primary language of expression, Grasi asserts his place as a national poet, refusing to be relegated to the periphery as a "marginalized minority." By affirming the Iban, Kayan, Kelabit, and Bidayuh languages as valid vessels for contemporary expression alongside Malay, Grasi disrupts the neat categories of linguistic identity that are played out in Malaysia’s politics of language.