In Their Own Words

Peter LaBerge on “Gust”

Gust

It begins with a question, and ends / with a plea. It begins with yes, I want / this world inside of me, and ends with prayers / in the attic. It begins with twelve forests and twelve / apostles to ravage them, and doesn't end until the bodies are forever / sealed shut. It begins with thousands / of curious boys, and ends with snow / the color of a fingertip. It begins and ends / with a body out of walking distance, with no one / to let the hunger out. It begins like this, I was / born quiet and slow. It begins, and the question / is just as empty as a new mother's deflated / belly. It begins with a young boy collecting / boughs, and ends with please, it is not winter / in my body. It begins and won't end until someone has mercy / on the woodpile. It begins with winter and cannot end / as winter. It begins a game and ends / a pistol in the ground. It begins / with metaphor, and ends with a boy running naked / and bloody through the forest / of his own skin. It begins and ends / in the length a bullet can travel. / It begins with hello, and ends / with the receiver nearly touching / the floor.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Gust"

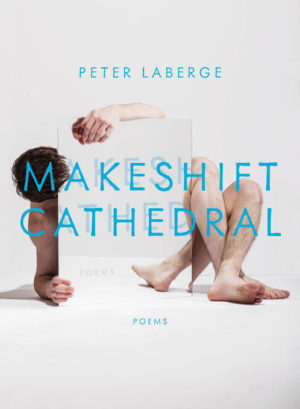

I wrote "Gust," the opening poem of my chapbook Makeshift Cathedral, while in a poetry workshop taught by Gregory Djanikian during my sophomore year at the University of Pennsylvania. That semester was home to a simple yet invaluable epiphany, the notion that poems don't have to look or behave like "poems" to be poetry. I soon realized that poetry could be queer—perhaps even inherently so—and that, centuries of gatekeeping by straight cisgender editors aside, elements of it always had been. This development propelled me to explore the queer body's relationship with small-town and big-city bigotry through some of the most overtly and unapologetically queer poems I've ever written.

To be sure, "Gust" does not present itself as an overtly queer poem, especially in comparison to Makeshift Cathedral's later poems. "Gust" is instead a poem concentrated on the subtle cycles of violence that suppress and silence queer individuals. In my mind, "Gust" documents the repeated genesis and subsidence of queer expression by connecting the chapbook's myriad personae: Diane Delia Ferrara, Will Jardell, Jesse Valencia, Jane Doe, Stacy Dillon, and others. From the set of America's Next Top Model to a trailer in Cleveland, Tennessee, the queer body bears both a constant sense of repression and an expectation of apology for its existence—both of which I strove to invoke and explore in "Gust."

There is simultaneous hope in recognizing the regeneration of the queer body and its urge to survive and persevere, especially in spite of such prolonged violence, prejudice, and fear. What writing Makeshift Cathedral taught me is that exposing the nuance of poetry is inextricably intertwined with exposing the nuance of gender and sexual identities. In this way, writing Makeshift Cathedral led me to contemplate how queerness manifests itself in art just as much as it led me to contemplate the relationship between queerness and the body. Over and over, it seems, our lives brilliantly and queerly end only to be begun again—in my view, poetry is the sign of unrelenting queer life.