In Their Own Words

Rachel Mannheimer on “Germantown”

Germantown

I didn’t know how to read the signs,

the hawk on the ground below the tree,

standing upright, the size of a dog,

the hawk on the fencepost out back

with a snake flashing green in its beak.

Sixteen vultures in the trees

around the scummy roadside pond, four on the roof

of a barn, sunning their outstretched wings.

The goldfinch on the backyard snag.

The wren in our woodstove who scrabbled

against the sooty glass, then went calm

so that I could reach in and grab him—

scooping him up in a dish towel

along with the ashes under him—

and carry him outside,

where he shot from my hands in flight.

The finch in our woodstove three weeks later

who wouldn’t settle, who, when I opened the door,

flapped frantic along the ceiling, then perched above the coat rack

on our basket of winter things.

The sparrow who, let out, hopped down

and pecked along the floorboards,

hopped across the welcome mat and out

onto the lawn. Then two wrens at once.

One disappeared like a dove.

When I saw the owl, it was because

the twilight had surprised me.

It started to rain,

I called Chris to come pick me up.

Any time he gets in the car it could kill him.

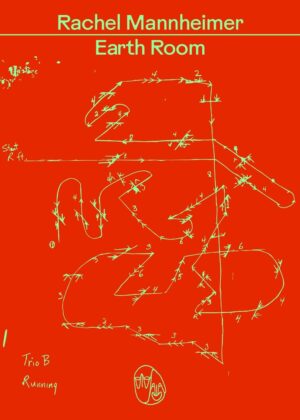

From Earth Room (Changes, 2022). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the poet.

On “Germantown”

This poem is a list of true bird encounters in Germantown, New York. It seemed to write itself; I tinkered with the sound.

In Germantown, we rented a house that was a lot like a barn, permeable. Doors and windows wouldn’t fully close; it was teeming with insects; I discovered a frog in our kitchen. And then there were these birds. They kept coming down our chimney into the woodstove. It was horrible to hear their feet scratching against the cast iron, their beaks tapping against the glass, to feel responsible for this terror and powerless to stop it. (Not totally powerless, of course. The chimney cap was broken; it just took some time to get someone out to fix it.)

The book, Earth Room, in which this poem appears, is about a lot of things: Land Art and other conceptual art of the 1960s and ’70s, dance and performance, catastrophe. It’s about one’s relationship to other beings and the environment, on a global scale and a smaller one. About learning to share space with a partner—and, I guess, in this poem specifically, learning to be apart without worrying that they’re dead. (It isn’t explicitly a book about the pandemic, but a lot of it was written or assembled in 2020, and I think there’s a certain anxiety in its pages. Feelings of portent, isolation, repetition…)

“Germantown” is not a comprehensive list of my bird encounters in Germantown. One evening, after the chimney was fixed, after the cold had returned, when a fire was burning in the stove, I came into the living room and saw a bird perched on our bookshelf. How had it gotten in?

The barn-like house was built into a rise, such that the garage became the basement. You could see down into it through the gaps between the floorboards, and through a few significant knotholes in the wood. It was accessible through a hatch in the pantry floor. My partner was down there doing laundry a few days later when I watched another bird fly up through the open hatch. It looked the same as the last one, which I’d identified as a Carolina wren. They must have been roosting in the beams. I read that they mate for life, stay together through the year and sing duets.

I miss that house. In retrospect, we should have known. We had occasionally heard their chirping, alarmingly clear.