In Their Own Words

Rick Barot on “The Names”

The Names

Now it’s time for the lilac, blazon of spring, the prince

of plants whose name I know only when it blooms.

The blooms called forth by a bare measure of warmth,

days that are more chill than warm, though the roots must

know, and the leaves, and the spindly trunks ganged up

by the trash bins behind our houses. The blue pointillism

in morning fog. The blue that is lavender. The blue that is

purple. The smell that is the air’s sugar, the sweet

weight when you put your face near, the way you would

put it near the side of someone’s head. Here the ear.

Here the nape. Here the part of flesh that has no name

at all, the part that is shining because it has slipped naming.

In the crumbling photo album, the dead toddler on a bier,

dead for decades, whose name I now carry. On another

page, the old man, also decades gone, whose same name

I now carry. The name a fossil, the calcium radiance

that I bear and will eventually give up. Again it’s time

for the lilacs. The quiet beautiful things at the sides of the

rec center parking lot. The purple surge by the freeway.

The sprigs I cut from the shrub leaning towards me

from the neighbor’s yard, taking them at night because

I shouldn’t be taking them. The blooms that are a genius

on the kitchen table, awful because I want to eat them

with my terrible eyes, with my terrible hands. The awful

lilacs, the brief lilacs, the sweet. Here is the recklessness

I have wanted. Here is the composure I have earned.

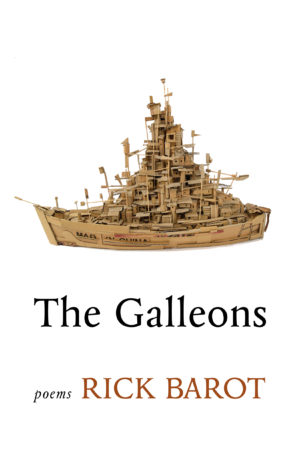

From The Galleons (Milkweed Editions, 2020). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author

On "The Names"

One of the best-known works by Albrecht Dürer is a watercolor of a hare, which he painted in 1502. The painting is astonishing for its meticulous detail, its warm realism. The painting is now in the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Austria. And though I’ve never been to the Albertina and seen the actual painting, I imagine that if I went there I would spend an hour or so looking at it.

One of the deep rewards of a long look at the painting would be arriving at the hare’s glossy right eye, in which Dürer has microscopically painted the reflection of the window of his studio. If you’re just looking at the hare, the hare is what you’ll see, and that will be illumination enough. But if you knew to look into the hare’s eye and saw the window there, you would find yourself in a place that includes not just the creature but also these other unfolding complexities: Dürer himself, the space where his thinking and dreaming and feeling happened, the space where his labor happened.

The window in the hare’s eye is where vision and the visionary meet. And what I find so wonderful about this little moment in Dürer’s painting is that it’s a secret. It’s there but not there. It’s like a wink, a direct gesture, from the man himself—one that happens so slyly that it barely registers.

The painting that contains a secret, and the secret itself containing other secrets—this is analogous to what I wish my poems to be these days. To me, “The Names” is a bit like Dürer’s painting of the hare. It’s ostensibly about one thing—the lilacs of spring—but the poem also contains a strange cargo—a meditation on my name and its legacy as something that has been assigned to numerous men in my family.

Enrique—this is my given name. It’s a name that, in the earnest assimilationist fervor of my late teens, I set aside for Rick. It was a complicated decision to have made, though my teenaged self wasn’t really aware of those complexities, and I don’t judge him now for the decision. Rickis who I am, and so is Enrique. An uncle who died as a toddler was also named Enrique, and so was a great-grandfather, and surely others before them.

“The Names” is about that swerve into family history even though I’d meant to write about the lush lilacs of that particular spring in 2016. The lilac, as I mention in the poem, is one of those plants that’s just a namelessly green shrubby thing when it’s not in bloom. But when it blooms, you suddenly know, remember, what the plant is. That was the poem I wanted to write, but the poem had additional plans for itself, and therefore the swerve.

One more thing. I see now that, in my poet’s mind, the image of the lilac is never far from Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In this way, the movement in “The Names” from description to elegy had been prepared for me by Whitman long ago. And so, Whitman is there, too—one more of the poem’s secrets.