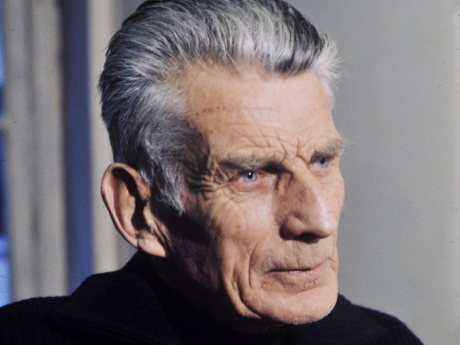

In Their Own Words

Samuel Beckett's “Cascando”

Cascando

1

why not merely the despaired of

occasion of

wordshed

is it not better abort than be barren

the hours after you are gone are so leaden

they will always start dragging too soon

the grapples clawing blindly the bed of want

bringing up the bones the old loves

sockets filled once with eyes like yours

all always is it better too soon than never

the black want splashing their faces

saying again nine days never floated the loved

nor nine months

nor nine lives

2

saying again

if you do not teach me I shall not learn

saying again there is a last

even of last times

last times of begging

last times of loving

of knowing not knowing pretending

a last even of last times of saying

if you do not love me I shall not be loved

if I do not love you I shall not love

the churn of stale words in the heart again

love love love thud of the old plunger

pestling the unalterable

whey of words

terrified again

of not loving

of loving and not you

of being loved and not by you

of knowing not knowing pretending

pretending

I and all the others that will love you

if they love you

3

unless they love you

Notes and history of 'Cascando' adapted from The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett, edited by Seán Lawlor and John Pilling

A letter to the poet and critic Thomas MacGreevy establishes the date of composition as early July 1936 (immediately after the completion of Murphy, which contains the phrase 'a slow cascando of pellucid yellows' in the penultimate paragraph of chapter 12), at which point Beckett seems to have thought of 'Cascando' as two poems (a follow-up letter twice refers to 'poems', and the two-poem idea gives extra foundation for the phrase 'saying again' at the head of the second section of the poem), sections one and two as published. The line that comprises the third section (with an upper case 'Unless') was sent in a later letter to MacGreevy ; MacGreevy had queried the opening section, which was in any event later to be omitted by Seumas O'Sullivan, the editor of Dublin Magazine, when he published it for the first time (O'Sullivan registered it as 'Two Poems').

The 'occasion' prompting the poem was Beckett meeting, and thinking he had fallen in love with, an American friend of Mary Manning Howe, Betty Stockton Farley, who did not reciprocate his feelings, although soon 'wordshed' seems to have taken over from those feelings. Beckett later remembered his feelings as a marker ('the Farley episode', when he was struggling unsuccessfully with another poem), but it was the poem that mattered. It looks back to 'Serena II' with the 'bones' of line 8 and to Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates, more generally– perhaps especially in Gedichte, which does nothing to indicate that it is not part of the Echo's Bones section that the book opens with – since its practice of 'saying again' generates the 'bare bones' of an echo. The second section echoes and expands the opening of MacGreevy's poem 'Dechtire': 'I do not love you as I have loved / The loves I have loved – / As I may love others'.

Midway through the Beckett's 'Whoroscope' Notebook, sandwiched between two entries in German, he writes and underlines: 'Cascando: praesectum decies ad unciam', (i.e. 'pruned down by a tenth to an ounce') with the last word doubly underlined. This is an adaptation (although no source is given) of line 294 of Horace's 'Art of Poetry': 'praesectum decies non castigavit ad unguem'. Horace's line describes how the poet's tenfold labour to attain accuracy has not been despised, whereas Beckett is no doubt reflecting on the labour he has expended on several versions of 'Cascando' to bring it to some kind of finality, while suspecting that, despite his efforts, it may not be well received ['castigavit' ]. Under the heading 'Surrealism' later in the 'Whoroscope' Notebook he quotes the opening lines of the 'Art of Poetry' in Latin, giving the source as 'Epistola ad Pisones'. Beckett had owned a polyglot Horace, bought in London, since the summer of 1932, and borrowed phrases from it for More Pricks Than Kicks, and for his 1980 Riverside production of Endgame (The Theatrical Notebooks).

The earlier entry ('Whoroscope' Notebook) was either made shortly before Beckett left for Germany in late September 1936, when he was practising his German, or shortly after his arrival there in October. In August 1936 he attempted to translate 'Cascando' into German (a language he had never been formally taught) on his own, partly just for practice and perhaps also in the hope of interesting any literary contact whom he might meet while away. In Germany, occasionally having sought the help of others, he made changes to this version throughout the end of 1936 and the beginning of 1937, sending a copy of his 'final' revised version to the novelist Paul Alverdes.. The German version ('Mancando', q.v.) is anything but a diminution, numbering 62 lines, where the English numbers 37 (32 in its Dublin Magazine version).

Beckett was relieved that MacGreevy had liked the poem, and describes the poem as 'the last echo of feeling' (a curiously apt phrase in the circumstances); and registered regret at its 'circumcision' by O'Sullivan: 'I think I told you about S O'S's request for an inch off the poem. Circumcised accordingly, it now begins with the abortion dilemma'. Beckett had told MacGreevy that the poem had been 'accepted', but he wrote again to say that: 'Seumas O'S[ullivan] sent another proof with request to make one line of two somewhere, anywhere, in the interests of his pagination'. In his German Diary entry Beckett ruefully remembers that there was 'no reason at all for him to have made me cut it'.

'Cascando' was first published in the Dublin Magazine, (Oct.–Dec. 1936) It was first published in book form in Gedichte in June 1959, and reprinted in August 1961 in Poems in English under the rubric 'Two Poems'.). A typescript of the revised version is in the Calvin Israel collection (Burns Library, Boston College). A carbon typescript copy of the poem, sent to George Reavey at his European Literary Bureau, presents it in four sections (as in the German version, 'Mancando'), rather than three. A typescript of Beckett's own German version is in the Lawrence Harvey collection at Dartmouth College. There are apparently other variant versions of 'Cascando' still in private hands.

Although the term 'cascando' is (rarely) used in music to distinguish a diminuendo in volume and/or tempo, Beckett continues to employ it for the next 30 years. He uses 'cascando' with reference to Waiting for Godot in a letter to Peter Hall in 1955, and then again in 1961 as the title of his 1961 radio play (originally written in French), which is not obviously about love and much more concerned with writing, Cascando (also the English title), with music by Marcel Mihailovici.

The BBC plan to broadcast 'Cascando', 'Malacoda' and 'Dieppe II' (i.e. 'my way is in the sand . . .') as verbal interludes on the 'Music Programme', first mooted in December 1967, had to wait until July 28, 1968 to occur. The poems were read on the Third Programme by Denys Hawthorne at 5.00 p.m. under the title Words and Music.