In Their Own Words

Sara Moore Wagner on “Getting My Body Back”

Getting My Body Back

By chance he put his eye to the keyhole. It was a feast-day and Donkey Skin had put on her dress of gold and diamonds … The prince was breathless at her beauty, her youthfulness, and her modesty (From Perrault’s “Donkeyskin”)

In the middle of the night,

I go into the butcher shop

through a keyhole in the back

door.

In the middle of the night

I go through a hole in the door

to get my body back. Imagine

someone looking through,

that I try each skin like a dress,

each one lovelier than the next—stables

in the heart open. They’re running. Chant:

beauty, beauty, beauty, like I’m a girl

again, like nothing ever happened

to my body, like I never hatched

open from the crotch, unlatching,

splintered, tear. Here,

when I get my body back,

there are no fingerprints on the hems,

no. And didn’t he promise, after I lost it,

to help me get it back or find

another. And didn’t I seek myself

in every coral grotto and pearl. Nothing

looks the same. Who are you?

I’ve put on my moon dress,

in the butchered light, discarded

the tired skin I wore the night

you stopped wanting me. And my mother

tells me no one will believe something

beautiful is inside something so

frightful. And when I put on my new

body, looking in, you might say

I see you,

and at last,

it will be so.

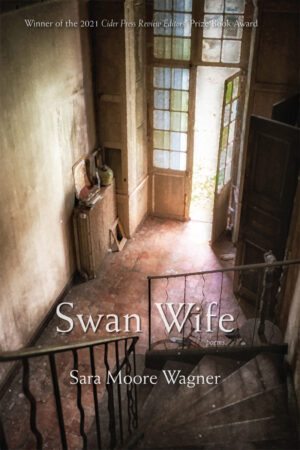

From Swan Wife (Cider Review Press, 2022). Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.

On “Getting My Body Back”

It wasn’t easy for me to get my body back after my first child. I gained sixty pounds and, after about two years, dieted myself down to the lowest weight I have ever been. I didn’t get my body back, really, then, I found myself awake in a new body.

As I was finding my new body, my relationship with my son’s father dissolved. Before I got pregnant, I discovered a journal in which my son’s father had written I would be “hot” if I were 20 pounds thinner. When we were breaking up, I reminded him of this, that he had never seen me as “good enough.” He said, “Now, you are.”

When my son was five, I remarried and got pregnant on our honeymoon. The journey of that first year is the subject of my collection Swan Wife, which is, on a larger scale, about learning to find oneself within the constructs of being a wife. As with the swan maiden stories where a swan’s coat is stolen, and she is forced to wed, it was necessary for me to be able to keep my wildness and not conform to domestic stereotypes and ideologies, which come from stories passed down (like fairy tales). I wanted to be happy in my marriage. For me, that meant working through the old narratives.

When I had my second child, a daughter, I again found myself in a new body, and it reminded me of the princess in the story “Donkeyskin,” a 17th-century Perrault fairy tale in which a king, grieving for his lost wife, wants to marry his own daughter. She holds her father off by requesting various extravagant dresses, including one made from the skin of his favorite donkey. She uses this skin to escape to a neighboring kingdom where she’s put to work. The prince sees her putting on her other fancier dresses through a keyhole and falls in love. She’s transformed back into herself, her clean, original self. This felt like what American culture in particular, expects all of us to do after the trauma of childbirth.

I got to obsessing. Who is the father in this story but those who lay claim to a woman’s body by right, who think their needs and suffering transcend all? Who is the prince but the one who will have her, provided she is presentable enough?

When I approach a fairy tale, I don’t want to retell it, as I have just done in this explanation. I want to tell you what it means to me, a woman who lives in a body and who, from time to time, is made to discard my skin for new ones. This poem sprang from my desire to show the man I love that nothing is my body; there is nothing I can get back or throw away. I am a creature in flux, and I will keep transforming into something else, whether he likes it or not.

Author photo by Christen Noel Kauffman.