In Their Own Words

Tishani Doshi on “A Fable for the 21st Century”

A Fable for the 21st Century

Existing is plagiarism — E.M. Cioran

There is no end to unknowing.

We read papers. Wrap fish in yesterday's news,

spread squares on the floor so puppy can pee

on Putin's face. Even the mountains cannot say

what killed the Sumerians all those years ago.

And as such, you should know that blindness

is historical, that nothing in this poem will make

you thinner, richer, or smarter. Myself—

I couldn't say how a light bulb worked,

but if we threw you headfirst into the past,

what would you say about the secrets

of chlorophyll? How would you expound

on the aggression of sea anemones,

the Battle of Plassey, Boko Haram?

Language is a peculiar destiny.

Once, at the desert's edge,

a circle of pilgrims spoke of wonder—

their lives dark with mud and hoes.

They didn't know you could make perfume

from rain, that human blood was more fattening

than beer. But their fears were ripe and lucent,

their clods of children plentiful, and God

walked among them, knitting sweaters

for injured chevaliers. Will you tell them

how everything that's been said is worth

saying again? How the body is helicoidal,

spiriting on and on

How it is only ever through the will of nose,

bronchiole, trachea, lung,

that breath outpaces

any sadness

of tongue

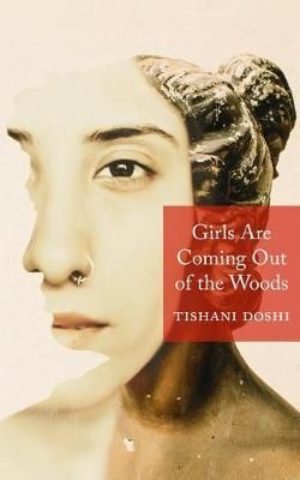

From Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods (Copper Canyon Press, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "A Fable for the 21st Century"

- I'd been thinking about the idea of knowledge versus information for some years. The poem grew out of a frustration of being bombarded with constant news — such as, will the Duchess of Cambridge give birth to a boy or a girl, is camel milk the next super food, did you know the Andromeda galaxy is 2.5 million light years away, etc. Increasingly, I felt that even though we were living in the age of information, the more I read, the less I knew.

- In an interview with Roberto Calasso, I asked about this phenomenon. He introduced a new word into the equation. Consciousness. According to him, science had said very little about consciousness. And while information was something everybody used and practised, consciousness was harder to pin down, and was most definitely moving in the opposite direction of information. He also said everyone should read the Upanishads.

- I frequently think about what I'd do if as in the movie Back to the Future, I was chucked back in time. What great discoveries could I make? Might I be able to describe how the light bulb worked? I could probably say something about "Om" but "ohm"? Definitely not. Or how to put together a punchy penicillin? Nope. The most I could do was inform cousin Homo erectus that yes, you're on to something there with those flints. Burn baby burn.

- Naturally, the accumulation of all I don't know and never will know made me feel much shame at my ignorance and dearth of general life skills.

- A friend invited me to stay in his mountain cottage in Mashobra, in the foothills of the Himalayas. This cottage was filled with books and arty films. Red-bottomed monkeys played havoc in the apple orchards outside, so mostly I stayed inside and read. This is where I discovered the aphorisms of EM Cioran. This particular line — Existing is plagiarism — unlocked the poem for me.

- The fable for the 21st century is the fable for the 20th century is the fable for the 19th century is the fable….

- There is no end to unknowing.

- But there was this realization that while I might not be able to invent, discover or explain anything, I could speak of wonder. I could rhapsodise.

- As humans we have similar concerns our ancestors had – does X love me or not? Will I die horribly? Would you look at that moon? Jeez, that bat scared the shit out of me.

- We may have more information but we are still beset by fears of mortality, feelings of anger, jealousy, vengefulness, love, adoration for dogs and the impulse to procreate.

- Which leads to a more universal question about poetry: Why bother?

- Everything has been said before, lived before and described before, so why bother writing your own two-bit poem when Sappho, Kalidasa, Rumi and several other greats have already set these things down?

- Because this is what we are wired to do. We are one of the few species that has the ability to document their experience of living in the world. Thousands of years ago we made cave paintings, and we don't know why – ritual, representation, dream, desire? Or simply to say, we were here! But the point is they could, and they did.

- And so maybe this is what we do – add our voices to the tapestry of all the voices that existed before us and will come after us. "Will you tell them that everything that's been said is worth saying again?" Yes, yes, yes.

- So the poem is really an apology in advance of there being no way my team will ever win a pub quiz. But also, an insistence on the wonder of the body. Of being alive. Of participating. Of trying to outpace any "sadness of tongue," to keep spiralling outwards with all our magnificent body bits that I surely wouldn't be able to point out on an anatomy chart, but I know they're there.