In Their Own Words

Wendy Xu on “Wang Xin Tai Says Goodbye”

Wang Xin Tai Says Goodbye

Some things are not so plain to say, that I

am sometimes in pain and occasionally sit

to write my name in dark inks and the brush

goes wobbly, as if excited into shapes

without me. The crop fields of someone’s childhood

still bother the edges of my vision, tawny

gridded country, low born, wind gripping the assembled

heads of wheat, bristling. One job seems now

just like another. I was a worker in a factory,

a prison, other places ill-defined. But I remember best

the war, the American G.I.’s. They taught me

my English swears, whole rooms cleared of men

and dogs as I cursed them up and down, my hand

on my little lieutenant’s hip, the green

and the muddy browns. In this life I even crossed

the ocean in an airplane, drank too many coca-colas

on the flight, ordered with flashcards

I stored beneath my hat. It wasn’t profound.

At the end, your life doesn’t really churn before your eyes.

It’s not a colossus that plays itself back

upon the eyelids like a final prayer. But the soda

was good, sweet. It popped and sang

on my tongue like English, someone remembering

me in the present tense.

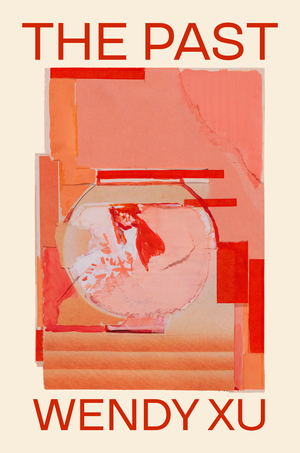

From The Past (Wesleyan University Press, 2021). Copyright © 2021 by Wendy Xu. Reprinted with the permission of the poet.

On “Wang Xin Tai Says Goodbye”

Wang Xin Tai was my maternal grandfather who passed away in 2018, and this poem is the only persona poem I have ever written. It appears in the title section of my book The Past, among other elegies for my Uncle, for the children I used to be, and the time I’ve lived through. While I was struggling through the writing of this poem, I thought to myself many times about how persona doesn’t comfort the dead, though I desperately wanted it to, and though it comforted me. I found the whole process unnerving, challenging, and at moments extremely moving as I learned how to sit with my grandfather inside the room of the poem—of course my grandfather in the poem exists only as a collection of the things he loved most to talk about, the most public and legible events of his life. And of course I sat with my grandfather as a way to sit with myself, my sorrow. As a poet I write in English, a language I often hate while at the same time the hours I spend creating with/in it keeps my alive, feeds my whole spirit. My grandfather’s life experiences were thoroughly in Mandarin Chinese, and English was, for him, solely for play—he knew exclusively curses and delighted in using them to shock and offend any potential English speakers in the room. How can I remember him, write him well, in this language? Does he hate this poem? Too proper. Though in life he wanted to be translated into English constantly, to hear his thoughts in my voice, the language I grew up inside. When he visited America he helped me practice my Mandarin, and I taught him animals and colors in English. When I remember him, as in the poem, I like to imagine him knowing he is being remembered, in all times and tenses—in English, the tool I’m resigned to use.