New American Poets

New American Poets: Arda Collins

Over No Hills

It civilizes me,

not like a private sense of bed

but that I have powers of speech at all—

I think I am going to stop

eating bits of paper

that don't say anything on them—

that don't even say anything on them—

I know I should do something

as they say, "for the snows of embarrassment"

like a day in March when the blood is closer,

day singing for the loss of its whip.

Closer, I say, closer.

Or maybe I'll arrange to have you run over by horses

unexpectedly.

At first it will seem terrible,

a wood-framed tableau in which you're torn limb from limb

or in what as a photograph an idiotic stranger will see and call "wild dust"

then ask about the car park,

something he says

that he brings out like a bow-legged cowboy walk

or leaning with one elbow on the counter.

He's our witness, how awful.

But eventually in our separate ways, we'll see the wisdom in it.

The horses are brown. They're from a painting

hanging in my once-room at the Hotel Phillips

in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

When the next day I saw sunset on the prairie

it gave the impression that the world would go on

as only grassland.

It was my wish

not to know

its reach.

I looked at it like a dog,

a dog waiting to be shot

with a long rifle,

or just a double-barrel shotgun.

O sweet shotgun, make the sun go down.

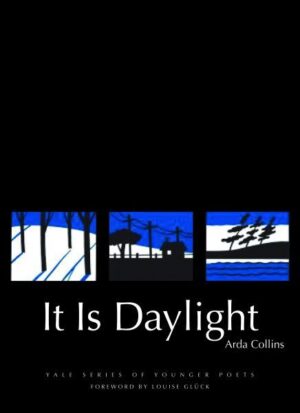

From It is Daylight (Yale University Press, 2009). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Poetry as a Process of Inquiry

The process of inquiry is one place that poetry comes from. Another way to say this might be that poetry is the emotion of the act of thinking; this might be true for poets like Stevens, Ashbery, and Dickinson. Being in a state of inquiry is pleasurable. It is intimate and private, and also meant to exist in the larger privacy of the invisible shared space of our psyches.

The feeling of inquiry, to my mind comes in many forms, in voiced poets like Pessoa or Vallejo, or in the exploratory gravity of sensation in Inger Christensen or Tomas Transtromer, in the force of speech that produces radical experience and sensation in Tomaz Salamun, and in the way Rae Armantrout transforms the kind of elusive turns of thought that graze our fields, into clarity.

I think of this process of inquiry, the desire to know, feel, or imagine something, to conjure a scenario, as a form of emotional intensity. When this happens in language, poems produce the thing you most want to say, maybe not every day and always, but in the dimension where the poem is taking place, in the imagination's interface with the world, this can be true, and it is also exciting.

Once for a job, I worked on a film where we were shooting small robots who could fly very small aircrafts, and when I say aircrafts I mean something like a motorized kite. This was taking place in a desert in eastern Washington. One night in my hotel, I smelled burning. What had happened was, there had been an accident with a woman driving a car, and a trailer. The desert was on fire, and all day it came closer and closer to the robots until everyone had to leave. We were tired and the cameraman became very drunk on pink wine in the airport restaurant. Then he became angry in the plane full of sleeping people and broke a piece of the airplane. We were still on the ground. He was asked to leave the plane and I had to go with him because it was part of my job. It was past two in the morning and we had to sleep in the terminal. This was regrettable, but it was also exciting. There were robots, a fire, someone breaking things in an airplane, and angry scenes resulting in embarrassing grief of all kinds.

When I think of this now, I am unsure about whether this happened, even though I know that it did. I don't know where it is but it is somewhere, and realistically it is many places. Everyone who was there is somewhere, even the fire, and the white pants my glamorous seatmate on the flight I never completed is somewhere. I'm somewhere right now.

There are animals, oceans, and the components of reality. Language about these and all things comes from the space inside of us, the actual physical space that joins us with the world, and it is one expression of the shape of our perception. Our biology is a cellular act of thought and emotion, and poetry is a sound it makes. I like something Chris Marker says in San Soleil that reminds me of what poetry feels like:

Shonagon had a passion for lists: the list of 'elegant things,' 'distressing things,' or even of 'things not worth doing.' One day she got the idea of drawing up a list of 'things that quicken the heart' . . . coming back through the Chiba coast I thought of Shonagon's list, of all those signs one has only to name to quicken the heart, just name. To us, a sun is not quite a sun unless it's radiant, and a spring not quite a spring unless it is limpid. Here to place adjectives would be so rude as leaving price tags on purchases. Japanese poetry never modifies. There is a way of saying boat, rock, mist, frog, crow, hail, heron, chrysanthemum, that includes them all. Newspapers have been filled recently with the story of a man from Nagoya. The woman he loved died last year and he drowned himself in work—Japanese style—like a madman. It seems he even made an important discovery in electronics. And then in the month of May he killed himself. They say he could not stand hearing the word 'Spring.'

Our inquiries in language are produced from the viscera inside of everything. As Octavio Paz says, "We are a pause of blood." Poetry is the sound of what comes before and after, and occurs in the duration.