Saying His Name

“A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, A Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon” by Gwendolyn Brooks

From the first it had been like a

Ballad. It had the beat inevitable. It had the blood.

A wildness cut up, and tied in little bunches,

Like the four-line stanzas of the ballads she had never quite

Understood—the ballads they had set her to, in school.

Herself: the milk-white maid, the "maid mild"

Of the ballad. Pursued

By the Dark Villain. Rescued by the Fine Prince.

The Happiness-Ever-After.

That was worth anything.

It was good to be a "maid mild."

That made the breath go fast.

Her bacon burned. She

Hastened to hide it in the step-on can, and

Drew more strips from the meat case. The eggs and sour-milk biscuits

Did well. She set out a jar

Of her new quince preserve.

. . . But there was something about the matter of the Dark Villain.

He should have been older, perhaps.

The hacking down of a villain was more fun to think about

When his menace possessed undisputed breadth, undisputed height,

And a harsh kind of vice.

And best of all, when history was cluttered

With the bones of many eaten knights and princesses.

The fun was disturbed, then all but nullified

When the Dark Villain was a blackish child

Of fourteen, with eyes still too young to be dirty,

And a mouth too young to have lost every reminder

Of its infant softness.

That boy must have been surprised! For

These were grown-ups. Grown-ups were supposed to be wise.

And the Fine Prince—and that other—so tall, so broad, so

Grown! Perhaps the boy had never guessed

That the trouble with grown-ups was that under the magnificent shell of adulthood, just under,

Waited the baby full of tantrums.

It occurred to her that there may have been something

Ridiculous in the picture of the Fine Prince

Rushing (rich with the breadth and height and

Mature solidness whose lack, in the Dark Villain, was impressing her,

Confronting her more and more as this first day after the trial

And acquittal wore on) rushing

With his heavy companion to hack down (unhorsed)

That little foe.

So much had happened, she could not remember now what that foe had done

Against her, or if anything had been done.

The one thing in the world that she did know and knew

With terrifying clarity was that her composition

Had disintegrated. That, although the pattern prevailed,

The breaks were everywhere. That she could think

Of no thread capable of the necessary

Sew-work.

She made the babies sit in their places at the table.

Then, before calling Him, she hurried

To the mirror with her comb and lipstick. It was necessary

To be more beautiful than ever.

The beautiful wife.

For sometimes she fancied he looked at her as though

Measuring her. As if he considered, Had she been worth It?

Had she been worth the blood, the cramped cries, the little stirring bravado,

The gradual dulling of those Negro eyes,

The sudden, overwhelming little-boyness in that barn?

Whatever she might feel or half-feel, the lipstick necessity was something apart. He must never conclude

That she had not been worth It.

He sat down, the Fine Prince, and

Began buttering a biscuit. He looked at his hands.

He twisted in his chair, he scratched his nose.

He glanced again, almost secretly, at his hands.

More papers were in from the North, he mumbled. More maddening headlines.

With their pepper-words, "bestiality," and "barbarism," and

"Shocking."

The half-sneers he had mastered for the trial worked across

His sweet and pretty face.

What he'd like to do, he explained, was kill them all.

The time lost. The unwanted fame.

Still, it had been fun to show those intruders

A thing or two. To show that snappy-eyed mother,

That sassy, Northern, brown-black—

Nothing could stop Mississippi.

He knew that. Big fella

Knew that.

And, what was so good, Mississippi knew that.

Nothing and nothing could stop Mississippi.

They could send in their petitions, and scar

Their newspapers with bleeding headlines. Their governors

Could appeal to Washington . . .

"What I want," the older baby said, "is 'lasses on my jam."

Whereupon the younger baby

Picked up the molasses pitcher and threw

The molasses in his brother's face. Instantly

The Fine Prince leaned across the table and slapped

The small and smiling criminal.

She did not speak. When the Hand

Came down and away, and she could look at her child,

At her baby-child,

She could think only of blood.

Surely her baby's cheek

Had disappeared, and in its place, surely,

Hung a heaviness, a lengthening red, a red that had no end.

She shook her had. It was not true, of course.

It was not true at all. The

Child's face was as always, the

Color of the paste in her paste-jar.

She left the table, to the tune of the children's lamentations, which were shriller

Than ever. She

Looked out of a window. She said not a word. That

Was one of the new Somethings—

The fear,

Tying her as with iron.

Suddenly she felt his hands upon her. He had followed her

To the window. The children were whimpering now.

Such bits of tots. And she, their mother,

Could not protect them. She looked at her shoulders, still

Gripped in the claim of his hands. She tried, but could not resist the idea

That a red ooze was seeping, spreading darkly, thickly, slowly,

Over her white shoulders, her own shoulders,

And over all of Earth and Mars.

He whispered something to her, did the Fine Prince, something

About love, something about love and night and intention.

She heard no hoof-beat of the horse and saw no flash of the shining steel.

He pulled her face around to meet

His, and there it was, close close,

For the first time in all those days and nights.

His mouth, wet and red,

So very, very, very red,

Closed over hers.

Then a sickness heaved within her. The courtroom Coca-Cola,

The courtroom beer and hate and sweat and drone,

Pushed like a wall against her. She wanted to bear it.

But his mouth would not go away and neither would the

Decapitated exclamation points in that Other Woman's eyes.

She did not scream.

She stood there.

But a hatred for him burst into glorious flower,

And its perfume enclasped them—big,

Bigger than all magnolias.

The last bleak news of the ballad.

The rest of the rugged music.

The last quatrain.

Terrance Hayes explores how Emmett Till has become a haunting, powerful figure in Black poetry—and Black public grief—through the work of 10 important poets. Subscribe to the PSA newsletter for more in the Saying His Name series and to keep updated with the PSA.

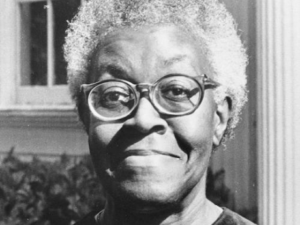

Terrance Hayes on “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, A Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon”

Someone, please make “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, A Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon” into a short, black-and-white, experimental film in the style of Andrei Tarkovsky. Brooks stages the poem wonderfully cinematically. She sets it up as an extended comparison opening “it had been like..." The filmmaker would be at liberty to include a scene where a white female actress sits baffled by a ballad spinning on her phonograph. Who should the actress be? You might cast someone resembling a young Carolyn Bryant Donham, but Brooks’ poem suggests the look of the white woman doesn’t matter. We know her name and that her accusation was false, but Brooks compels us to see her as a cipher, a metaphor with thoughts and feelings. The tone of the poem is allegorical, bone-chilling, and matter-of-fact, at the same time. Everything is infused with terror: the recognition (“the Decapitated exclamation points in that Other Woman's eyes”) and the intimacy (“Suddenly she felt his hands upon her”). Much of the short film should probably be set in the kitchen. The camera should zoom and hold on a skillet of burning bacon for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Brooks sets the reverberating horrors of racism in the domestic. The woman is a muse to monstrosity, yes, but she is not a monster in Brooks’ lens. She is humanized by her anxiety, her shame and guilt. Brooks does not reduce the subject to evil. The poem makes me ponder how human fear metastasizes into cowardice; how human longing and hunger metastasize into selfishness. Brooks depiction of the fears that stoke the woman’s imagination is both an act of empathy and an act of damnation.