The Poet’s Nightstand

The Poet’s Nightstand with Jane Wong

Who’s Your Daddy

Arisa White

When I read the line “Am I the site of abandonment?” in Arisa White’s Who’s Your Daddy, I felt something unmoored within me rattle. I found White’s book after writing my memoir (which engages my absent father), and I so badly wish I had this book with me during the writing process. Hybrid poetry and memoir, Who’s Your Daddy moves with narrative and evocative intensity – negotiating White’s estranged relationship with her father through Guyanese proverbs, Shango dreams, and ancestral voices. I underlined nearly every sentence, which reverberated with visceral loss and lyric questioning. Moving across Brooklyn and Guyana, Who’s Your Daddy reckons with the past through the present-future. As Christina Sharpe writes in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “In the wake, the past that is not past reappears, always, to rupture the present.” Each line felt like a wound pulsating, with language quaking in what is absent/present: “I’m cutting fatherlessly.” White also speaks vulnerably to intimate adult relationships and loneliness, entangling queerness, class, and familial trauma: “I couldn’t vow to a blade that knew my insides soft.” I was utterly stunned by this book and have kept returning to it in my own thinking and feeling.

Purchase

Side Notes from the Archivist

Anastacia-Reneé

In 2021, I met Anastacia-Reneé at her exhibition (Don’t Be Absurd) Alice in Parts at the Frye Art Museum. She told me that she visited her exhibition often, watching visitors move through the installation—watching white women turn and look away. Photographs from the exhibition appear in Side Notes from the Archivist, beginning with an image of a door. Reneé reimagines language through haunting repetition, litany, mix tapes, altars, and sensory memory. Throughout, the archivist insists on ancestral memory: From “Section I. Retroflect”: “— says ‘remember’ / — writes to remember / — remember? / — remembers everything.” Invocation is an act of radical love and these poems celebrate and constellate Black femme lineages. From “Black Marsha (P) Johnson”: “black marsha / i see your rouge / reflecting black / at me in the hudson.” Exacting in her tonal fuckery, she critiques systemic oppression with sharp realness: “Calling in Black Today: “i’m calling in [black] today. / actually, this whole weak.” Reneé also has a new book coming out in March 2024, Here in the (Middle) of Nowhere. Reneé is a visionary in hybrid poetics, where multiple portals open to demand resplendent communities of love.

Purchase

Hydra Medusa

Brandon Shimoda

Brandon Shimoda’s Hydra Medusa is a continuance of The Grave on the Wall, a memoir that has stayed with me like little seeds. Hydra Medusa weaves together dreams, longings, incisive sociopolitical critiques, and elegies that unfurl buried bones. Each image feels saturated with synesthetic surrealism: “I had a dream last night that a rainbow was burning. // I had a dream last night that the war fit on the tip of a finger.” There are images of a woman pulling black hair out of sink drain, islands folding in half, the sun leaking. Hydra Medusa spills out the guts of surveillance, empire, and the police state: “the world we think we love is / scar tissue.” I felt these poems in my teeth. Alongside poems, lyric prose sections question who is an ancestor and what it means to become an ancestor, in a world of daily violence: “I have come to believe something: that life is preparation for the possibility of becoming an ancestor. The possibility materializes through vigilance, responsibility, love.” Speaking in the recurrent ghostliness of the Japanese American internment, Shimoda’s daughter sings in the book: “Remember? / We live in the desert / Remember? / I have rocks in my hand / We’re almost closer.”

ballast

Quenton Baker

To hear Quenton Baker read from ballast – with poems read in multiple directions, multiple versions – is to hear the continual expansiveness of a silenced history, across and through time. ballast speaks to a successful large-scale revolt of the American-born enslaved people on the ship Creole in 1841. The revolt has been recounted in US Senate documents, but there is little known testimony from the 135 enslaved people who escaped. Demanding redress, Baker redacts Senate Document 51 of the second session of the 27th US Congress in 1842. From Baker’s afterword: “Washing the Bones”: “I don’t think I had any other option except to use [the document] as the text for this project. Simply put, it made me angry, and I wanted to do something with that anger. Rage and anger and violence are byproducts of living in an anti-black world.” Visually, moments of the erasure embody visceral rage, with blocked-out swipes of ink moving in vertical directions (usually horizontal), such as on page 68 with the text: “consider belonging to the slave.” The poems in the second half of the book are precise, “heavy with asking.” Each syllable has a sonic echo: “bless each blade we buried in a deserving belly.” The haunting echo of “and then what” resounds alongside the revolt of language: “new syllables shaped around spasmodic collapse.” ballast also declares deep love in this necessary act of redress: “we the lived-in rupture / the recollection of breach // a deeper love than any deity can imagine.”

Purchase

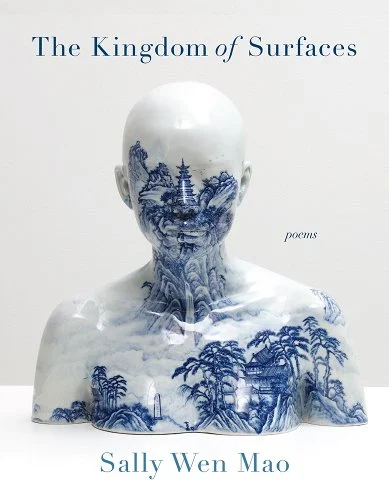

The Kingdom of Surfaces

Sally Wen Mao

I was lucky enough to be an early reader for Sally Wen Mao’s The Kingdom of Surfaces (as well as Reneé’s and Baker’s books above). The Kingdom of Surfaces is the most vulnerable and ferocious of Mao’s collections thus far. From the opening poem “Loquats”: “In different years // of my life, 2012 and 2017, two men / with the same name fucked me. Futility // was their name. Their bald heads, their kisses, / the spittle of spite, crawl into me, refusing to exit.” Continuing her work in Oculus, with a nod to Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism, Mao undoes empires tied to porcelain and silk. From the series “On Porcelain”: “For millennia, // the West has attempted to replicate / Porcelain / and failed.” These poems visually echo the shape of vases, with sharp cuts of blank space. The Kingdom of Surfaces also grapples with the terror of the COVID-19 pandemic, with all its violent, racist spittle. From “Batshit”: “Say it. Say it to my face.” The long poem “American Loneliness” contends with hypersexualized violence (including the forgotten history of immigrant Chinese women being sold as sex slaves in San Francisco) and the rage of constant grief: “… the American obsession with freedom is the American obsession with death.” Woven through this collective horror is a deeply felt connection—a haunting reality in its elegiac continuance: From “Aubade with Gravel and Gold:” “I’m sick of speaking for women who’ve died / Their stories and their disappearances / bludgeon me in my sleep.” And later: “They sailed, they sailed, they sailed through me / and I turned gold with that touch.” That touch ignites the rage within Mao’s lines, longing for safety.

Purchase

Jane Wong is the author of the debut memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, out now from Tin House (2023). She is also the author of two books of poetry: How to Not Be Afraid of Everything from Alice James (2021) and Overpour from Action Books (2016).

Author photo by Gritchelle Fallesgon.