Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Daniel Owen on Afrizal Malna

Four Poems by Afrizal Malna

Eraser's Guest

It’s a shame this poem’s already been erased when

I go to read it. Like humid air that tugs

at my arm to catch what will fall, is

falling, and falls. What’s up with erasing? Glue,

scissors, and yarn make a shadow of barbed

wire. I erase the word erase from the documentation,

out from the barbed wire. Return each word

to glue, scissors, and yarn so as to

hide, lose, and erase once again

the word erase. And a knock

that’s never been erased inside a shadow’s

death: a guest from a door’s shadow that’s never

knocked on the door.

The guest suspects I don’t have a chair to

die in if I don’t have a floor to live on. Waiting.

Waited on. Plans at 7 p.m. They serve the word

eraser from a bookstore to their guests,

like a shadow that’ll slip away from its light.

You’re my guest who I wait for from the mistake

of typing the word erase in a story about

a brilliant morning and birds in flight

drifting away erasing their own chirps.

You don’t have another chance to tidy what no

longer can be erased, after this poem. An eraser

makes five o’clock in the evening. Comes through till its

vacancy can no longer be seen.

Techniques to Entertain the Viewer

The coffin’s joy in saying happy new year.

I mean, coffin and new year.

Words move across it and fall like birds

shot in biology class.

Intellect, that feels it could be a mediator

between body and reality, topples from the bookshelf.

I mean, topples and bookshelf.

Period and comma lost in a period-and-comma trap.

Words subjugated by the dictionary’s storm.

Split again between storm, between dictionary.

A bossa nova in the middle of a library fire.

Split again between music and fire in the library.

“Mr. Entertainer, Sir,” I say so as to see my spirit

amongst a collection of housing costs and

football match tickets.

A wash bucket in a heap of city dwellers.

Applause of perfume producers

and a printing press from a hospital.

Thank you.

Mr. Entertainer, Sir.

Thank you.

Ears of Revoltuion

I’m faithful to you, comrade. Be faithful to me

while eating sate and losing your sate skewers. I’ll

be faithful to you, comrade. Look at my wounds,

are you faithful enough to sit and to stand? You’re faithful

to me while reminding me to sleep and drink

warm tea on Monday mornings. I see your faithfulness

like the party’s fidelity on a Sunday holiday.

Be faithful to Monday and to Sunday,

comrade. Be faithful enough to applaud before

my corpse. And scream and shout when the factory

puts out goods and commodities, trucks carry

goods and commodities, stores and shops and homes and houses

carry goods and commodities.

Be faithful when traveling between cities, announcing

changes in the price of phone minutes at every moment. Be faithful

enough to forget the smell of a nation like the smell of a thief

hiding in his own home. Comrade, do

you have the funds to steal your fidelity? Don’t

trip over your own feet. Don’t trip over your

own mouth, comrade. Don’t trip, comrade, over

your own eyes. All ears are gathering

here, comrade. Ears of revolution that

read the smell of bananas. And feel it when

your mouth, your mouth, falls to the soles of your feet.

A Street to Fall on

You sit that plastic-wrapped heart down on my

desk chair, sit down to light up a poem. Scent of

plastic and corpse perfume. A rainy season so

warm and so January. You sit me down,

the one who’s standing on my desk chair, standing to see

what keeps falling. Toward what’s lying around

and what’s floating away. Toward what’s running after

the fall of all I don’t need to own.

Translated from the Indonesian by Daniel Owen.

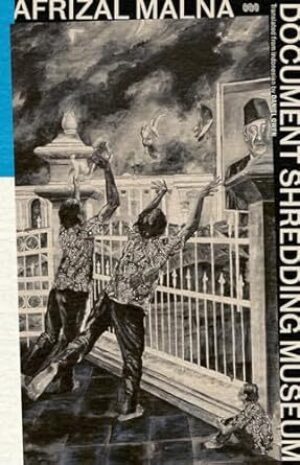

Reprinted from Document Shredding Museum (World Poetry Books, 2024) with the permission of the publisher and translator. All rights reserved.

On Afrizal Malna

Afrizal Malna’s poems are deeply engaged with the problem of time and the related problem of history, the narration of what happens in time. Born in 1957 and raised in the Senen neighborhood of Jakarta, Malna grew up through a period of intense political and economic turbulence—from the years of President Sukarno’s Guided Democracy to the cataclysmic anti-Communist violence of 1965-66 that ushered in General Suharto’s New Order military dictatorship through the Cold War period which saw Suharto’s authoritarian imposition of economic development as the guiding principle of national ideology. This was a period marked by rapid and aggressive industrialization, what historian and writer Sony Karsono calls Jakarta’s “accelerated modernization.” Coming of age in the midst of these radical changes, Malna felt himself part of a “lost generation”—the first generation of Indonesians, or so he speculates, severed from the roots of their home cultures and languages and delivered into the lap of an inchoate national language and culture, vulnerable to the machinations of state puppetmasters and their global interlocutors. Though both of Malna’s parents hailed from West Sumatra and spoke the Minangkabau language with each other, they never taught their mother tongue to their children, speaking with them instead in Indonesian. Malna’s sense of linguistic rootlessness and cultural disconnection was compounded by the intense social, economic, and technological changes happening at the time: the mass introduction of telecommunication devices, the development of consumer culture, the prevalence of motor vehicles, the ongoing demolition and reconstruction of the city. The experience of change in the interlocking gears of various scales and speeds and significations of time (and the fractures and fissures that abound where these gears touch) has been a central concern of Malna’s throughout his writing.

His first book of poems was The Running Century [Abad yang Berlari]. Published in 1984 by a group of college friends from Driyarkara School of Philosophy who pooled their funds to produce the book, The Running Century was a slim volume of rebellious, angst-charged lyric poems. It would go on to win the Jakarta Arts Council’s poetry award and establish Malna as a promising young poet among the new generation of Indonesia’s writers. When Malna reread the poems after the book’s publication, however, he found them false and alien, out of touch with the everyday reality he experienced in Jakarta. In his view, they conformed to the expectations that contemporary literary critics and poets had set out for Indonesian poetry, musings of a lyric-I that staged existential urban angst tempered with Sufi longing (very much en vogue in the late 70s/early 80s) against a backdrop of Mooi Indië mountains and seas, a glorified prelapsarian homeland ideal far from the potholed streets and basketball courts and broken refrigerators of his Jakarta. These poems, as he would later put it, were Indonesian poetry, not his poetry. Following this realization, he turned his energies to developing a poetic practice that would allow him to write his own poems, from his own bodily, material experience rather than the ready-to-wear poetic materials rendered by the dominant literary culture. He took two contradictorily complementary steps to cultivate this practice: experimenting with somatic exercises to bring his body and its consciousness to the fore in his writing; and reading deeper and wider in the corpus of Indonesian poetry, ultimately composing a series of critical essays that map the major currents in the language’s modern verse, collected in the doorstopper volume Indonesian Something [Sesuatu Indonesia] (2000).

His somatic explorations were closely related to his engagement with Teater Sae, an avant-garde theater company that focused on bodies and objects as the site of dramatic activity. In the texts he produced for Teater Sae, Malna attempted to treat language as an object for the actors to perform with, a sort of dimensionless prop. He also began to experiment with collage, appropriation, and related strategies of documentary and conceptual poetics, practices which would only become prominent in his poetry writing in the late 2010s.

The poetry Malna wrote during the years he spent working with Teater Sae (the mid-80s to the mid-90s) took the form of image-oriented prose poems densely and chaotically peopled with the stuff of emergent mass consumer culture in a rapidly globalizing postcolonial megacity: microphones, truck tires, chocolates, refrigerators, tv’s, postcards, donuts, tissue scraps, soda cans.[1]

By bringing all these unpoetic objects into the realm of human action in the space of the poem, Malna shocked the Indonesian literary establishment. The poems were considered difficult, dingy, obscure, ugly, unapologetic, unpoetic. The syntax was blurry, so that the relationship between agent and object became unfixed and the temporal order of events indeterminate. A sort of post-humanist vision, which would later come further to the fore in Malna’s digital-era poems, began to emerge. These were the first fruits of Malna’s efforts to write from the body rather than language, collected in Anxiety Myths [Mitos-Mitos Kecemasan] (1985), The Quiet in the Microphone [Yang Berdiam dalam Mikrofon] (1990), and Rain Architecture [Arsitektur Hujan] (1995).[2]

Malna conceives of the body as a site of direct personal and collective experience, of raw connection with others, objects, the world. Language, on the other hand, is thought of here as the economically and politically manipulated discourse of the era, when the totalitarian ambitions of the New Order attempted to control all media and police language use through cultural institutions and policies. These government programs were situated on the frontlines of the Cold War’s socio-cultural front. They were aimed at limiting and regulating the significatory possibilities of language, its potential to mean multiply, paradoxically, difficultly, differently. Malna’s work increasingly pushed at the limits of meaning, subverting this control and opening spaces for critical consciousness. One particular formal strategy Malna employed to bring this off is what he calls berpikir dengan gambar—thinking in, or thinking with, images—an essentially collagic practice of arranging linguistic images and narrative fragments in surprising combinations to shake up predetermined meanings and associations and allow new paths of connection to develop among the scripts of socio-historical narrative.

In the late 1990s, as the military regime’s grip on civil society began to loosen, Malna became active with the Urban Poor Consortium (UPC), an NGO that worked to empower Jakarta’s urban poor communities, supporting their efforts to become participants in city policy and preserve their livelihoods and homes in the face of violent evictions spurred by developmentalist policy. The UPC was part of a broader social movement that contributed to bringing about the resignation of President Suharto and the beginning of political reform in May 1998 (a movement and historical moment commonly known as reformasi) in the midst of mass social unrest following the economic collapse caused by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The intensity of this period’s social, political, and personal upheaval animates Malna’s poetry collection No Dog in My Mother’s Womb [Dalam Rahim Ibuku Tak Ada Anjing] (2002), and his novel A Hole Made of Half the Sky [Lubang dari Separuh Langit] (2004), works that draw on his experiences with the UPC.

Disappointed by the lack of substantial social change and disillusioned with cultural life in Jakarta, Malna stepped away from his position as a public literary figure for a few years in the early 2000s, moving from the capital city first to Solo and then to Yogyakarta, small cities in Central Java rich in the cultural heritage of classical Javanese arts. Ironically, Malna’s work after stepping away from the Jakarta limelight garnered him greater attention from national and regional literary institutions: My Friends from the Roof of Language [Teman-temanku dari Atap Bahasa] (2008) was awarded a SEA Write Award and Document Shredding Museum [Museum Penghancur Dokumen] (2012) a Khatulistiwa Literary Award. Written while living in Nitiprayan, a rural area of Yogyakarta, Document Shredding Museum marked a shift in Malna’s poetics. Leaving the prose poem form that had been his MO since the mid-80s, Document Shredding Museum primarily employs the modernist convention of using line breaks to build music and tension, and includes the odd diagram and list poem as well. Perhaps more significantly, this book saw Malna begin to explicitly engage with the legacies of Indonesia’s past, exploring the conjunctions and disjunctions between memory, mythology, and history as they play out through the fabric of everyday life in an increasingly global, increasingly digital era. The mass proliferation of the internet coincided with the loosening of state media control and censorship, resulting in an explosion of newly accessible information. With Document Shredding Museum, Malna began to utilize this newly available data to devise a poetry that blurred the expressive collagic image-thought of his earlier work with documentary poetics’ use of archival documents and factual details.

This new phase of Malna’s work—augmented by digital technology and documentary data—was developed further in Berlin Proposal (2015) and Open the Left Door [Buka Pintu Kiri] (2018) and reached its apex with Prometheus Pinball (2020). Berlin Proposal was written in Berlin as a DAAD artist-in-residence in 2015. The book experimented further with digital drawings, visual poetry, and archival photographs lifted from the internet, forms that Malna would continue to explore in subsequent work. Living in Berlin, Malna was deeply affected by the city’s approach to dealing with traumatic historical memory and by the artists and artworks he encountered there. Among these was Singaporean multimedia artist Ho Tzu Nyen—a fellow DAAD artist-in-residence at the time—whose work uses recombinatory audio-visual collage techniques to refresh perspectives that have ossified in official national and regional historical narratives.

After returning from Berlin, the question of how to deal with the past—how to navigate the twisting, often forking paths of memory, historiography, and ideology—became central to Malna’s poetics. In Malna’s reckoning, the New Order infected Indonesia with a “history epidemic”—a proliferation of lies and machinations, manipulations of historical fact and meaning from recent to ancient— in order to legitimize the military regime and justify the atrocities committed to bring it to power. Rather than seeking to revise the dominant historical narratives, Malna’s work utilizes the vast stores of information made available through the internet to seek out surprising coincidences and collisions between personal memory, public narrative, and historical record. In doing so, these poems seek to lift open the full-stop-shaped lid of History and invite a bunch of question marks to take its place. These works of documentary collage Malna describes as pencangkokan arsip, archive grafting or archival transplantation. The term “pencangkokan” evokes both medical and agricultural imaginaries, visceral and vegetal textures. It’s the term used for organ transplantation and for plant grafting, a method of propagating new trees and shrubs by grafting one plant—selected for its stems, flowers, or fruits—onto another plant selected for its healthy roots. It is the conjoining of aspects of distinct entities in order to preserve or generate life. Through this practice, "archives are released from the constructions of history and transplanted into other bodies so that their identities shift and undergo a broadening of significance," as Malna put it in a recent critical essay[3]. It’s like thinking in images with appropriated documentary materials as its source. The pinnacle of such practices, his 2020 collection Prometheus Pinball, is an epic work of "autopoetry." It is at once an autobiography, a history of Jakarta, and a discordant index of objects, impressions, narratives, and memories, wherein poems are often comprised of the collision between bits of trivia derived from google-searched timelines of world history and contemporaneous stories and images from Malna’s life and the life of Jakarta.

In early 2020, shortly before the publication of Prometheus Pinball and the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, Malna moved from Jakarta—where, after returning from Berlin, he had been engaged as the head of the Jakarta Arts Council’s theater division—to East Java, where he continues to reside. Contrary to his claims that he’d probably be done with poetry after the long, difficult process of writing Prometheus, Malna has been quite active in the past few years, writing and publishing two new poetry collections and publishing several compilations of critical essays on performance art, visual art, and poetry. Shot in a Mask, Hmm… [Tembakan dalam Masker, Hmm…] (2021) deals with the “new normal” era through loopy experimentation with poetry, short stories, recipes, and digital drawings, while the poems of Entrance Ticket to the Autobiography Cinema [Tiket Masuk Bioskop Autobiografi] reflect on empathy, autobigraphy, the aging body, and the specter of death amidst data banks, social media, and technological warfare.

Ah, time is ever a question that poetry can’t but ask. Malna’s writing is a poetry that both finds itself in history—inhabiting, propelling, reflecting its time—and conscientiously records its own time, extending possibilities for the approach to history, writing the present into the future. A practice like sweeping the porch or fixing a hole in the roof. When I last visited Malna, a few months ago at his home in Sidoarjo—an industrial town located on the far reaches of Surabaya’s urban sprawl—he said he hadn’t been writing lately, just painting the walls of his house and tending to the daily washing and sweeping. I was reminded of writings and past conversations about his enjoyment of household chores, how he discusses these activities not as a separate kind of undertaking, but one closely related to writing poetry. Repetitive processes that make the body aware of both its presence in time and its immediate relationship with the world around it.

My thoughts keep coming back to how Osip Mandelstam’s famous image about poetry and time—that poetry is a plough turning up time, bringing its deepest layers, its abyssal strata, to the surface—might translate into Malna’s poetics. In Malna’s thinking, the layers of time, at least as far as we can encounter them through language, are all mixed up. Deep and shallow, near and far, known and unknown, ordered and disordered. We could use a metaphor less romantic and further removed from agricultural life—something more Jakartan—but every bit as humble, daily, and useful. Rather than a plough, perhaps a stove[4] is more fitting as Malna’s poem-image figure—that lowly yet dignified appliance that turns raw materials into sustenance and is found in both intimate household spaces and throughout the streets, in the food stalls that proliferate throughout the city—where the products of the black soil of time are all cooked up together, in surprising combinations, and served up hot.

Afrizal Malna is a poet, artist, and writer of short stories, novels, literary essays, and playscripts. His work has won a number of national and international literary honors, including the SEA Write Award and the Khatulistiwa Literary Award. His most recent books are the essay collection Performance Art dan Medan Pasca-Seni (Performance Art and the Post-Art Field) and the poetry collection Tiket Masuk Bioskop Autobiografi (Autobiography Cinema Ticket). He was a 2015 DAAD Artist-in-Residence (Berlin) and has performed at poetry festivals in Bali, Bremen, Maastricht, Hamburg, Kerala, and Yokohama. His work has been translated into Dutch, English, German, Japanese, and Portuguese. His books available in English translation are Document Shredding Museum, Morning Slanting to the Right, and Anxiety Myths.

Daniel Owen is a poet, translator, and editor. His translations from the Indonesian of Afrizal Malna’s Document Shredding Museum were chosen as the winner of Asymptote Journal's 2019 Close Approximations contest. He is the author of the poetry books Toot Sweet (United Artists), Restaurant Samsara (Furniture Press), and Celingak-Celinguk (Tan Kinira). Recent writing and translations have appeared in Tripwire, Two Lines, Circumference Magazine, and Harp & Altar. He edits and designs books and participates in many processes of the Ugly Duckling Presse editorial collective.

[1] As George Oppen put it, “there are things / we live among ‘and to see them / is to know ourselves.’”

[2] A selection of poems from these books was translated into English by Andy Fuller and published by the Lontar Foundation in 2013 under the title Anxiety Myths.

[3] See “tema-tema primer dalam kerja kreatif saya” in Kandang Ayam (DIVA Press, 2021).

[4] In a 2019 interview published in Jacket2, Malna says “I’m like a stove that can cook whatever. And I’m not the cook. I’m just the stove. So we can imagine that my poems emerge from that stove.”