Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: James Nolan on Jaime Gil de Biedma

Three Poems by Jaime Gil de Biedma

A BODY IS A MAN’S BEST FRIEND

The hours aren’t over, not yet,

and tomorrow’s as far away

as a reef I can barely make out.

You don’t notice

how thickly time is growing in this room

with the lamp glowing, how the chill

is outside licking at the window panes . . . .

How quickly, little creature, you fell asleep

in my bed tonight with the easy nobility

born of necessity while I studied you.

So good night then.

That quiet country

bordered by your body’s contours

makes me want to die remembering life,

or to stay up —

exhausted and excited — until dawn.

Alone with old age while you sleep

like someone who’s never read a book,

funny little creature: so human —

much more sincere than in my arms —

because a perfect stranger.

DE VITA BEATA

In an antique land where nothing works,

something like Spain between two civil

wars, in a village next to the sea,

here with a house and few possessions

and no memory at all: neither reading,

suffering, writing nor paying bills,

and living on like a bankrupt count

among the ruins of my intelligence.

DURING THE INVASION

The morning paper lies open on

the tablecloth. Sunlight glints in

the glasses. A workday, I eat lunch

in a small restaurant.

Most of us fall silent. Someone’s speaking

in indistinct tones — talk especially saddened

by how things are always happening

and drag on forever, or end in disaster.

I imagine it’s dawn around now in the Ciénaga,

everything uncertain, no pause in the fighting

and in the news I search for a little hope

that doesn’t come from Miami

O Cuba in the fleeting tropical dawn

when the sun’s not hot and the air clear:

may your land sprout tanks, your shattered sky

turn gray with the wings of your planes!

The sugar-cane people, the streetcar man,

the folks in restaurants are with you

and all of us today who search the world over

for a little hope that doesn’t come from Miami.

Translated from the Spanish by James Nolan.

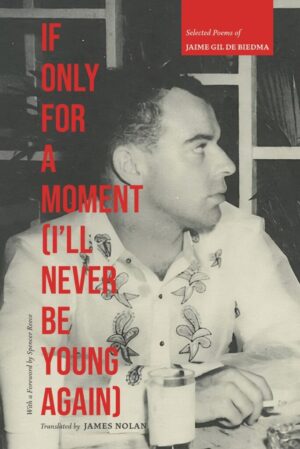

Poems reprinted from If Only For A Moment (I’ll Never Be Young Again) with the permission of the publisher Fonograf Editions.

On Jaime Gil de Biedma

Americans may be struck by two wildly contradictory images of modern Spain: a gypsy talking to the moon in a García Lorca poem, and skipping a generation, the espresso-pot earrings dangling from María Barranco in Pedro Almodóvar’s film Women On the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. This dramatic transition from the rural gypsy mythology of García Lorca to the wacky urban libido of Almodóvar crosses the desert of the Franco dictatorship. Despite the popularity of Spanish poetry, little is known here of the post-Civil War poets, who chart this painful course from defeated idealism to ironic postmodernism. The foremost poet of this era, Jaime Gil de Biedma, leader of the “Barcelona school,” has become a cult figure in contemporary Spain since he died of AIDS in 1990. His poetry and legend help to explain who the Spanish have become and how they survived when, for almost half a century, the lights went out.

The first edition of Gil de Biedma’s selected poems wound up, as might be expected, in boxes in the publisher’s basement, censored by the government. His life and literary career were bracketed almost entirely by the rise and fall of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, notorious for the suppression of literature. Born in 1929, Gil de Biedma was six years old when García Lorca was murdered in Granada at the outbreak if the Civil War, and his collected poems, Las personas del verbo, first appeared in 1975, the year Franco died. What is surprising is that Gil de Biedma was a leftist, homosexual poet from the Catalan capitol, Barcelona – all of Franco’s favorite things – who not only published books of autobiographical poetry in Spain but was known as a poet of social conscience as well as erotic lyricism. Like other Spanish poets of his time, he chose his words carefully.

Gil de Biedma is the most original and influential among the poets known as the 50’s Generation. In a poem of that decade, “In Luna Castle,” he addresses a political prisoner just released from Franco’s prison. The long years behind bars are a “gorge separating / those moments from these . . .a chasm in your spirit / you can never bridge.” This chasm between the revolutionary ferment before the Civil War and the police-state that followed is as abrupt as the war itself, and as broad and deep as the ensuing industrialization of Spain and the exodus from countryside to city. The poetry of the previous generation — of García Lorca and Rafael Alberti — was an expansion of the romantic imagination, a passionate poetry with a magical sense of language. Although socially committed, this poetry was on the whole rural, an oral poetry as memorable for semi-literate listeners as for educated readers. The ravaged landscape after the Civil War did again produce poetry, although it is as different from that of the generation of ‘27 as if it came from another country.

Children during the Civil War, Gil de Biedma’s generation was an orphaned one. Their cultural parents were killed, exiled or imprisoned, and the Spain of their youth was the gray impoverished city dominated by curfews, shortages and censorship. But the loss that most affected these poets is what George Orwell sees as the ultimate result of totalitarianism: the destruction of the national language. Public language was corrupted not only by Franco’s control of the media, education and religion but also of the connotations of words themselves. Dios no longer meant God, Familia was not my family or yours, and Patria was not where the Spanish lived. What Ignacio Silone writes about Fascist Italy was equally true in Fascist Spain: “He who speaks, lies.”

Gil de Biedma subverted the lie of the very language in which he wrote with irony, parody, and humor, weathering out an exile-at-home with cunning. He substituted a liberating cosmopolitanism for the loss of his own culture, and what he gained was to join the larger tradition of twentieth century European poetry. For his generation foreign culture was a crack of light under a bolted door: A trip to Paris, books from London meant everything to him coming of age as a poet. His greatest influences were not only Luis Cernuda and Jorge Guillén but also French Symbolist and Anglo-American poets. Eliot and Auden especially are echoed in his poetry in the soft-spoken conversational voice, the recycling of foreign sources and the undermining of old poetic rhetoric. Often Gil de Biedma’s words fall into place in English translation as if coming home to the source of their inspiration.

…

Gil de Biedma was a poet who outlived his era, as he himself knew best. Yet his recent cult status in Spain is due only partly to the sensationalized media accounts of his homosexuality and death from AIDS. The freedom imagined in his defiant, sensual poetry has been realized during the past decades, when Spanish cities have become an all-night whirl of bars and discos, a high-decibel celebration fed by hashish, open sexuality, outré fashions and the most tolerant attitudes, straight out of an early Almodóvar movie. The Spanish, however, have not forgotten a generation of repression or those who helped them to transcend it.

In this sense, Gil de Biedma is a poet of the “in between,” as are many of his contemporary readers who live wedged between conflicting social identities and historical eras. As a post-war child, he spent his adult life in between the repressive Franco era and the explosive freedom that followed the dictatorship. As a leftwing dandy, he lived in between a career as a prosperous businessman and a close identification with the socialist poets of the clandestine resistance. His body of work is located in between the solidarity of this youthful idealism and the isolation of a more circumspect middle age, fraught with the realization that he’ll “never be young again.”As a gay man during an era in which homosexuality was a felony, he lived in between a feigned respectability and an erotically active underground. And he died during a pandemic, one which at that time in Spain dared not speak its name.

An excerpt from "Poet of the In-Between" by James Nolan, from If Only For A Moment (I’ll Never Be Young Again) published by Fonograf Editions.