In Their Own Words

David Woo on “The Leaf Blower among the Swimming Pool Lights”

The Leaf Blower among the Swimming Pool Lights

From inside your headphones, behind the chirring decibels,

the white rumble of stars, syncopation of falling stars,

the artifice of a blue cosmos in illuminated water—

you are late for home, late for the mangoes and the rice.

Each movement you make parts another family's serenity,

parts it and restores it to the clear, aside a pyramid of leaves.

Chaise longue, splayed oak, sprinkler's translucent gravity.

Is it for them you bind exigencies with a bow and release

to thoughtless pastoral the flat, green essence of a lawn?

If inside you is a blue pool full of stars, it is never yours.

You own only the specter of coins in someone else's yard:

a garden's footlights, a blue moon, a watery constellation.

Who is she but your young wife holding aloft a scallop shell

of marble spilling water in the dusk? You would hold her,

and in the vigil of your arms you would vanquish the dust

of the world by carting it closer to where she awaits you,

owning it, inhabiting it, with her, aside her, at the dusty pale

of the city, dove shot sleeking and spinning a bright tin can.

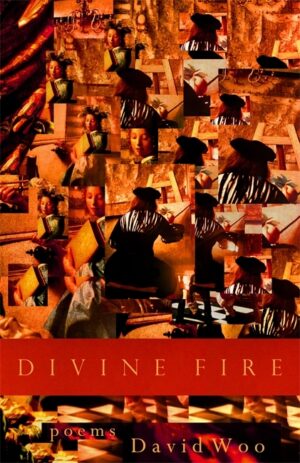

From Divine Fire (Georgia Review Books, 2021). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “The Leaf Blower among the Swimming Pool Lights”

The history of immigration in America tells us that the lives of immigrants—like the worker in my poem, who guides a leaf blower in the beautiful yard of an affluent American family—will always be precarious, even if an election alters policies for the better. “The Leaf Blower among the Swimming Pool Lights” is one of two “Leaf Blower” poems in my book Divine Fire. Whereas Andrew Marvell’s mower poems were, in part, an exploration of the division between nature and human artifice, the “Leaf Blower” poems explore the artifice of divisions in American class and race and nationality. They are an evocation of people we see in every American city and especially in the southwest where I live, the hard-working immigrant gardener or manual laborer, whose human dreams are so much vaster than the abstractions of policy and the brutal diminutions of racism. My late parents were immigrants full of dreams, so my task here was not to flinch from the material beauty that was part of my character’s private aspirations but to make them subsume the affluence against which they rose and fluttered. One way of doing so was to imagine the leaf blower’s dreams turning to love. I wanted the rapture of the love language that I found in some of my favorite Spanish-language poets, like Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, and Luis Cernuda. And I remembered how my father, on his rare days off, would take his troubles to the dusty edges of the city and shoot tin cans as target practice for the dove hunting that he dreamed about but never experienced.