In Their Own Words

Douglas Crase on the poems of Donald Britton

Heart of Glass

Every act expresses a wish, surviving

A lot of living and shifting

Into new forms of a sad decorum

Like a science uncommitted to the facts:

Squinting into the sun like one

Getting old very fast, the past something

Made of bricks laid end to end

To the top of yon hill of waves

And sinking, thinking still of you

For whom no wave grieves, no radio

Goes dead, but mentioned in the

Acknowledgments for various kindnesses.

Then, awakening, the day is perhaps

Too young to hurt you, still adulterated

With remembered pain and hope

Whose emblem is the paradisiacal slope

Of light on the Poster Child's

Limp, empty sleeve. Either that,

Or the beautiful seed at the heart

Of an apple, which promises that this

Corny emotionalism can go on

Indefinitely, sluicing into the shape

Of its own ingenuity as light pours

Into its speed, the bubble you are

Floating in reducing all that floor plan

To wasted space, the gaudy interior

Of a Venetian bead painted to resemble

Someone's idea of how time would look

If the distances between things could be

Squeezed into a corner to make room

For what it takes from us, leaving behind

Instructions for reproducing the diorama

Exactly as it happened, in the same way

To each of them, so that in the end

Personal history was annihilated, ground

Into a very fine talc and gathered

Into structures of air that are always

Collapsing. Such was the benign, giddy

Environment in which Freddy found himself,

Though as yet somewhat queasy about

What the Fire-God had told him, feeling

Not unlike the disgorged meal of a panther,

Chewed by something black and terrible

But retaining his essential substance,

Putting all the rest behind him

Like a buried parent, to become the hero who,

Elated at the portrayal of things beyond his ken,

Shouldered his people's glorious future.

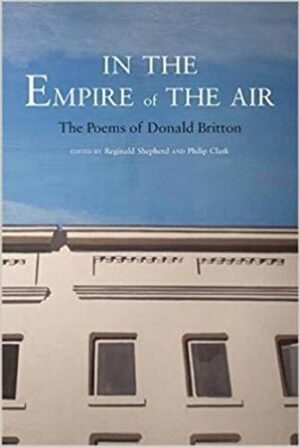

From In The Empire of The Air: The Poems Donald Britton (Nightboat Books, 2016). All rights reserved.

The following essay is an excerpt of Douglas Crase's afterword to In The Empire of The Air: The Poems of Donald Britton, edited by Reginald Shepherd and Philip Clark.

* * *

The appearance in print of the selected poems of Donald Britton is an affront to cynicism and a triumph over fate. When Donald died, in 1994, it was sadly reasonable to assume that the influence of his poetry would be confined to the few who had preserved a copy of his single book, the slender, deceptively titled Italy, published thirteen years earlier. As the few became fewer it seemed all but certain the audience for his poems would disappear. Donald never taught, so there were no students to mature into positions of critical authority. There was no keeper of the flame to incite publication, no posthumous foundation to subsidize it, not even a martyrology in place to demand it out of sentiment. The survival of his work would have to come about, instead, as a pure instance of "go little booke"—an instance that must now warm the heart of anyone who has ever believed in poetry. It was the poems in Italy themselves, free of professional standing or obligation, that inspired the successive affections of two remarkable editors and the confident publisher of the present selection. Donald, who despite his brilliance was a modest and self-effacing person, would be surprised.

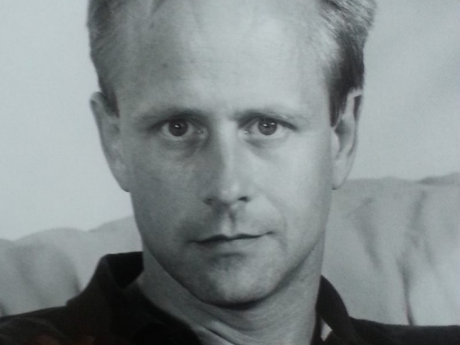

I met Donald on New Year's Eve, 1978, at a crowded party hosted by Michael Lally in his loft on Duane Street in the section of Manhattan since called Tribeca. The first thing one noticed about Donald, having registered already at a distance that he was blond ("dirt blond," he once corrected me), was the beauty of his high forehead. His eyes were blue, or 298U in the Pantome matching system (he informed me of that, as well), familiar today as the color of the Twitter logo and known sometimes as Twitter blue. But the arresting feature was the forehead, a placid expanse that seemed the emblem of intellect and imparted to his face an overall composure that persisted through even the most animated moments. The effect could be misleading. It defeated the initial efforts of painter Larry Stanton, whose portraits of Donald's friends Brad Gooch, Tim Dlugos, and Dennis Cooper are eerily ideal to anyone who knew them, but whose attempted likeness of Donald, as part of a triple portrait with Tim and Dennis, resembles the demented hitchhiker of your worst nightmare. The forehead has distorted the face, and each fix Larry applied—he even changed the haircut—made the image less satisfactory. A subsequent effort, the double portrait of a noir Dennis and beatific Donald, was dramatically more successful. Larry was so pleased he kept this second painting a secret until its exhibition at a private gallery in the East Village, where Donald would see it for the first time the night of the opening.

Donald came to New York from Washington, D.C., following the example of Tim, who likewise had followed a trail blazed earlier by Michael Lally. In Washington, Michael was a founder of the Mass Transit reading series that gave Tim and other now prominent poets their early audience. By the time Donald lived in Washington, Mass Transit had been replaced by an equally influential series sponsored by Doug Lang at Folio Books. Here Donald found his own early audience. In those years, whether in Washington or New York, one's circle of poet friends was fluid, social, and embraced a heady mix of Language-centered writers and latter-day disciples of the New York School. You could meet Bruce Andrews at a party and not fear you had compromised his aesthetic. Donald thus took for granted that there was more than one way to articulate the times, and he respected any poetics that would approach the task seriously. That he himself approached it seriously is apparent from his work of this period: "La plus belle plage," with its careening nouns that nonetheless verge on narrative, or "Notes on the Articulation of Time," with its observation that "We need / these narratives, we want them." One might conclude he had therefore chosen sides, as Kenward Elmslie implied in a blurb for Italy claiming Donald as a "super-Ashbery-of-the-Sunbelt." But if that was humorous then, it is misleading today. The early "Serenade" (which I hadn't seen until Philip Clark obtained it from Donald's correspondence with a friend) is a reminder of a moment in our poetry when it was possible to conceive of uniting Eliot and Hart Crane, under the tutelage of Mallarmé and perhaps the wary eye of Pound, and so make an end run around Ashbery altogether. If Donald came out sometimes at the place Ashbery was to occupy a week later, well, this made the result no less worthy and gave him an insight, meanwhile, into the reproducible strategies of genius.

Taking up residence in New York put Donald in contact with a wider circle of writers and artists, many of whom still basked in the glow generated by Ashbery and the other poets known originally as the New York School. Dennis Cooper, who was to live in the city from 1983 to 1985, described in a later interview the excitement of being introduced to that circle by his friends. "I'd go to a party with Tim and Donald and Brad," remarked Dennis, "and there would be slightly older writers like Joe Brainard and Kenward Elmslie and Ron Padgett, and then the established greats like Ashbery and Schuyler and Edwin Denby, and nonpoets too, like Donald Barthelme and Alex Katz and Roy Lichtenstein and just an incredibly multigenerational group of artists, gay and straight, who felt some kind of aesthetic and personal unity." That unity was more than notional. The figures named (all male, but there were women at those gatherings, too) shared for the most part a faith in chance and daily experience, a faith that whatever came in through the open window would be redemptive and nourishing, or else no worse than a disappointment, which would be nourishing as well. Tim and Eileen Myles adapted this faith to liberating effect; Eileen tagged it accurately as an aesthetic of "exalted mundanity." But Donald had his doubts. He had acquired a good dose of skepticism from his Language-oriented colleagues in D.C., internalized the skepticism of Shakespeare while performing the plays at the University of Texas, and probably learned, long before, the survival skepticism of the wise child who grows up in a provincial town. Tim occasionally wrote parodies of his poet friends and the one he dedicated to Donald, "Qum," already captured Donald's growing unease with the poetics of exalted mundanity and Language both: "Wanting people to desire us / we (meaning you and I) wear a bright veil / of language (meaning words) before which pale / the mundane elements of waking life."