In Their Own Words

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. on “The Obstacle”

The Obstacle

The lush green didn’t move. An obstacle

that wasn’t there lay ahead of me.

There had been rain.

It was the memory of an obstacle,

unmarked on my modern map, waiting,

its shining barbed coils dripping in the morning air.

An advance had been anticipated here.

All around it the beginning of the day swirled, as if

my sudden attention to it, struggling with its dimensions,

was another wave of confusion

in khaki, and then what always followed:

the waverings, occluded, falling to pieces, their lines

now only to indicate elevation….

If I change my position

it becomes easier to see. Shadowed by the edge of the wood,

lying low, coiling and recoiling itself, practicing.

Each time waking itself with its sharp reminders.

Every now and then the sound of a car passing. Around it

full summer crowding into what should be

a black and white photograph—protection—

the vacationing family again, on bicycles, moving

unhindered and quickly.

It refuses to look,

patient, waiting, resisting, resisting

still the very idea of advance. Patient,

but without compassion. And I

still near the edge of the field, of the wood,

between the field and the wood, waiting

for some gap, a way through.

Then some kind of flare hovering

illuminating the daylight, filling the hollowed ground, then

implacable endurance, the residual

stubbornly held on to, history

again material, catching

at my clothes—some kind of affirmation—

until there it is, all of it—spider wire, snarls

of concertina, knife rests, chevaux-de-frise,

until the thing itself—as seen here

or from the air, quivering, spooling

back on itself, revealing the rest, where it was—

is for a moment clear.

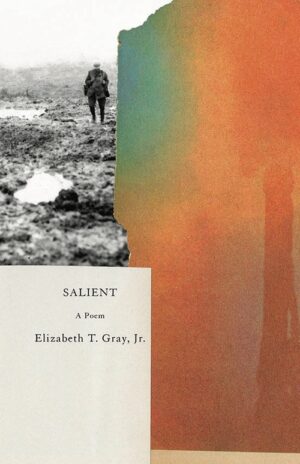

From Salient (New Directions, 2020). Copyright © by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. Reprinted with the permission of New Directions Publishing.

On "The Obstacle"

The obstacle described here is barbed wire, rows of carefully entangled and interconnected snarls of barbed wire built in front of British front-line trenches in Sanctuary Wood near Ypres in Belgian Flanders in June 1916. Rows of wire designed to protect British and Canadian soldiers from waves of German infantry. Rows of wire which are no longer there. Had you been riding by with the family on a bicycle on that summer day in 2016 you could not have seen the beginning of the trench system, with its saps and parapets and traverses, nor the expanse of barbed wire, thirty feet across, lying in wait in shallow hollows in front of the firing trench at the edge of the wood.

Salient, the long poem from which this section comes, is about trying to see. Trying to see the Great War, a war that remains unimaginable to us: waves of exhausted men advancing slowly uphill for weeks in relentless rain through waist-deep mud into artillery and machine gun fire in order to capture a few yards of strategically insignificant ground. The poem is about trying to get one’s bearings on a battlefield dotted with tiny streams through meadows, snug little houses, glossy EU-subsidized cows, fields of sugar beets, vacationers, and cemeteries. It’s about trying to find the almost 90,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers who fought in the Ypres Salient and vanished there—drowned in mud or vaporized by artillery shells—and who have no known grave. At the dedication of the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in 1927 Field Marshal Herbert Plumer, who had commanded British Second Army in 1916, assured grieving families, “He is not missing. He is here.”

If you look carefully, if you are attuned to what happened where, if you have the maps from 1916, if you pick the right time of day, it’s possible to see the War. It may grant you access to itself. “Obstacle” is about a morning when the wire let itself be seen, when it tugged at my clothes. It’s still there.