In Their Own Words

Florencia Varela on “The Ministry of Memory”

The Ministry of Memory

VII

It’s a building

I’ve seen

one thousand times.

If you’ve seen

anything

one thousand times,

you know:

in grief,

we own.

When I own,

I exist.

I go on

to take on

everything to heart.

What I own

I can bury.

When that

baby died,

and it wasn’t

mine,

that was

that.

She was born

when she was

buried.

When I try

to say anything

one thousand times:

That was

that.

In my Paris

Nothing happened.

I charm myself.

I will have

always had.

She with old

eyes and cats,

she who lost

a child,

buried herself

into the city’s walls.

I will always

have that.

In grief,

we build.

A building I had

seen one thousand

times over.

When I own,

I exist.

Without warning

I remember

everything

about her face.

I always have.

If you’ve heard

anything:

to be a woman,

to be a city,

is to bury—

in—

in spite—

in spite of.

On “The Ministry of Memory”

This poem had been in knots for over four years—first drafted in 2016, first published in 2017, and in a continuum of iterations until it landed as the end poem of a collection. It began as a portrait. After years of not returning to Buenos Aires, I finally made plans to return in 2016. A priority, outside of visiting a community of family and friends, was to seek out the Kavanagh building, built in 1936 as a spite house—a brick and mortar manifestation of a grudge between two families.

By the time I landed in Buenos Aires, a series of griefs had begun compounding. My body would not be able to become pregnant (at least not without heavy scientific intervention). Two women I knew suffered miscarriages. My mother’s mother’s dementia progressed significantly every day. The Trump presidential campaign publicly embraced racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric. It felt, and ultimately was, impossible to unbraid these events, especially when standing in the shadow of a vengeful monument.

The mother goes, the mind goes, the body goes, our histories go. Everything must go. And while the going never ended, I did observe a small moment of power. I started understanding grief as an act of ownership, a final claim.

The poem leans on repetition as a coping mechanism. I had to repeat to myself several truths, like “charms”, and allow them to create layers, allow them to stabilize the shifting foundations, allow them to grapple. I had to name the baby and the building—through incantations, I had to allow them to become the foundation itself.

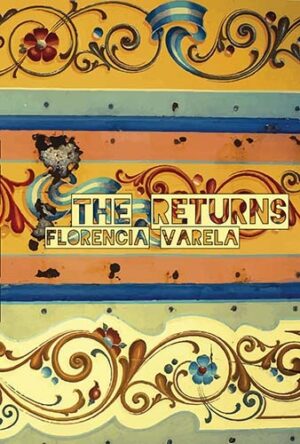

The collection, The Returns, ended up growing from and around this poem, even as it continued moving through edits and iterations. The piece itself became my own spite house—a stake I put in the ground, as I tried to reconcile the immense history and potential that a body can carry for both creation and grief.

Four years later and it’s still impossible for me to separate building from burying. We now live in extraordinary times, framed by unprecedented loss and pain and accented by a fragile American democracy. We will not escape the collective grief, but especially after writing this poem and reading it innumerable times, I now ask of me, of us, how we will build beyond spite?