In Their Own Words

Kit Schluter on Jaime Saenz’s “The Cold”

The following poems are the first two sections from Bolivian poet Jaime Saenz's 9-part 1967 long poem, El frío, as translated from the Spanish by Kit Schluter under the title of The Cold, and recently published by Poor Claudia. The subsequent prose excerpt is the final two paragraphs of Schluter's afterword to the translation, written in direct and intimate address of Saenz himself, over thresholds of distance, language, and mortality.

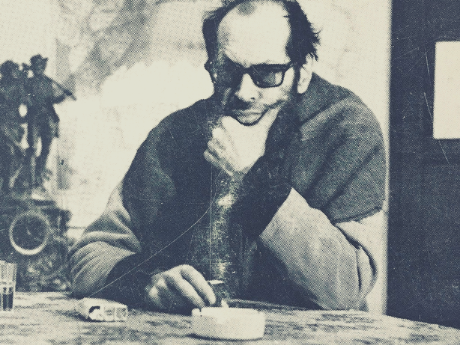

Jaime Saenz was born in 1921 in La Paz, Bolivia, the city where he was to spend his days until his passing in 1986. Poète Maudit in letters and life, Saenz was rumored to have stolen a limb from a corpse at the university morgue, and to have brought a panther home to his wife on their wedding day. It was around his now notorious, magical Krupp Workshops that a generation of young La Pazian poets burgeoned, and his body of work was the first Bolivian, and among the first Latin American, to openly explore bisexual experience. He lived nocturnally, excoriating the false divisions of body and language, debauchery and exaltation, and life and death in his many novels, plays and volumes of poetry, including El Escalpelo, Los papeles de Narciso Lima-Achá, and Muerte por el tacto.

The two previous English-language translations of Saenz's poetry are Immanent Visitor: Selected Poems of Jaime Saenz (University of California Press) and The Night (Princeton University Press), both of which were translated by Forrest Gander and Kent Johnson. Saenz's significant body of prose, plays, and novels remains untranslated.

* * *

An excerpt from The Cold

1

In the streets, I realize the state of the world,

I think of leaving at once in pursuit of the cold and confronting the devil who hides beyond the shadows

and asking him why it is only in the land of the cold that something as useful as life may be found,

that voice I miss and need to hear before I go,

if I already know that, in this world, the only thing that resembles its celestial accent is the smell of alcohol,

and with all I say and all I do, all I do is give things time:

in one corner hides the glacial alcohol, the alcohol of the cold, and in another corner I hide,

each of us awaiting the other’s exit, understanding there is no escape from this bad joke, you already know;

on Christmas, on New Year’s, on national holidays, on birthdays,

every time I escape by a hair, later I start walking quickly and joyfully and keep an eye out over my shoulder

—I already know, in the corner is someone more patient than me, he is a giant, he is a colossus, and I a poor worm,

and perhaps that is why I stay alone and fascinated,

how strange,

and for that same reason I wonder what’s going on in the world,

when the cold does not exist and I start to shiver, and I don’t listen to your voice and the cold remains,

so, this is very curious:

the voice is the temperature.

2

And absence is the absence of some voice, and in absence there is no temperature,

since it is only for the reunion of a thing and itself that temperature appears, and later time’s unfolding makes itself felt

—and to make sense of such questions, I imagine my face is a face identical to yours,

the same goes for finding you, but I have to take in the burning aroma

—the day when the sky spreads out and the stars fall into the city,

some metal, one of your eyes, a certain light, will have to fall into to my hands,

one way or another I will have to know what became of you and what became of the fog;

to listen to your words and what you say, I do not know what I would give, I am dying to touch with you the end of things

—I am dying to know what is said, what is not said and what would like to be said of your adventures.

On Jaime Saenz

Your language short-circuits the immediacy of our bodies, Jaime, the immediacy of touch, and yet I sense in it the argument that, without language, there would be no I to yearn for you, no you to touch me; desire and its satisfaction would occur more or less meaninglessly—that is, they would simply occur, and without value. Or that, without language, there would be no such thing as "desire," no such thing as "touch," merely sensations and unspooling durations, accordioning together and apart at given, though unchartable, moments. This absolute sensuousness of our bodies (half of the unresolvable equation of experience) saves us from being subdued by pure language, the temporal logic of its tenses, the subject-object sequencings of its syntax, the rigid-bodily coordinations of its prepositions, the spiritual vectors of its pronouns: all of this grows entangled in our viscera. For life to be lived and not merely occur, word needs to be exceeded by flesh, and flesh by word: in this back-and-forth, the body feels its speech and speaks its feeling. In the dissonance of this harmony is found that something that must be called life.

Has anyone ever told you, Jaime, that your language makes too much sense? That it makes so much sense that we don't know how to make sense of it anymore? Has anybody every told you that your language is too excited by the basic fact of its being language? I'm taken by this excess of sense in your language, Jaime, which I find opens up, however paradoxically, the space for the body of the reader to participate in your work. When the body's physicality exceeds the senses, it speaks; where the mind can no longer make sense of language, the body and its sensuality enter the processes of linguistic understanding. I like to think of this as your argument: that where there is logic there is also sensuality, and, given their standing as complements, their event is the same. Their concurrence, occulted by too much attention paid to either one, takes place perhaps nowhere but in the excesses of their paradox and the seeming impossibility of its ever taking place anywhere at all.