In Their Own Words

Natalie Diaz's “Hand-Me-Down Halloween”

Hand-Me-Down Halloween

The year we moved off / the reservation /

a / white / boy up the street gave me a green trash bag

fat with corduroys, bright collared shirts

& a two-piece / Tonto / costume

turquoise thunderbird on the chest

shirt & pants

the color of my grandmother's skin / reddish-brown /

my mother's skin / brown-redskin /

My mother's boyfriend laughed

said now I was a / fake / Indian

look-it her now yer / Indin / girl is a / fake / In-din

My first Halloween off / the reservation /

/ white / Jeremiah told all his / white / friends

that I was wearing his old costume

/ A hand-me-down? /

I looked at my hands

All them / whites / laughed at me

/ called me half-breed /

threw Tootsie Rolls at / the half-breed / me

Later / darker / in the night

at / white / Jeremiah's front door / tricker treat /

I made a / good / little Injun his father said

now don't you make a /good / little Injun

He gave me a Tootsie Roll

More night came / darker / darker /

Mothers gathered their / white / kids from the dark

My / dark / mother gathered / empty / cans

while I waited to gather my / white / kid

I waited to gather / white / Jeremiah

He was / the skeleton / walking past my house

a glowing skull and ribs

I ran & tackled his / white / bones / in the street

His candy spilled out / like a million pinto beans /

Asphalt tore my / brown-red-skin / knees

I hit him harder and harder / whiter / and harder

He cried for his momma

I put my fist-me-downs / again and again / and down

He cried / for that white / She came running

She swung me off him

dug nails into my wrist

pulled me to my front door

yelled at her / white / kid to go wait at home

go wait at home Jeremiah, Momma will take care of this

She was ready / to take care of this /

to pound on my door but no / tricker treat /

My door was already open

and before that white could speak or knock

/ or put her hands down on my door /

my mother told her to take her hands off of me

taker / fuck-king / hands off my girl

My mother stepped / or fell / toward that / white /

I don't remember what happened next

I don't remember that / white / momma leaving

/ but I know she did /

My mother's boyfriend said

well / Kimosabe / you ruined your costume

wull / Kimo-sa-be / you fuckt up yer costume

My first Halloween

off / the reservation /

my mother said / maybe / next year

you can be a little Tinker Bell / or something /

now go git that /white / boy's can-dee

—iss-in the road

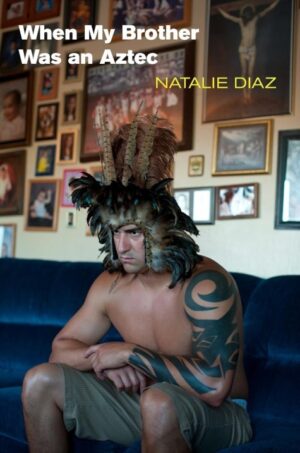

Poem reprinted from When My Brother Was an Aztec (Copper Canyon Press, 2012), with the permission of the author. All Rights Reserved.

On "Hand-Me-Down Halloween"

Intro

"Hand-Me-Down Halloween" was almost the title poem of my first book. It has no epigraph, but if it did, it would have one of the following:

1. This really happened. — Me

2. None of this happened. —Me

Backstory

I did move off the reservation for a short time, to a neighborhood of railroaders' kids, a place we had always called "Up On The Hill" while we were living at the bottom of the hill, across the tracks on the rez. The year we moved "Up On The Hill," my little brother and I fought everyday against the same kids whose parents sent us fat Glad garbage bags of hand-me-down clothes and shoes. One of those bags had a Tonto costume in it, along with a reversible Dracula cape (red on one side, black on the other). We fought those kids for many reasons: they called us names, they teased us, they never shared, they made us drink out of the hose while they went inside to drink Tang, they stole back the broken-down second-hand toys they had given us, and worse, at school they told everyone that we were wearing their old clothes. We also fought with them because we were angry at and hungry for bigger things than them, and even simpler, because we were good at it. Fistfights were our great equalizer in those days. Our corner of the street was like the corner of the ring, and from it, we were undefeated.

Finally, I got a hold of one of those boys. I really worked him over is what my mom told my aunt over the phone later. Yes, the railroad boy's mother did march down the street like a small cavalry, to my house, where my mother met her at the edge of the yard in a giant war party of big hands on thick hips that only a pissed-off native woman can be. I might have been crying when the little white cavalry mother lifted the boy's split chin for my mother to see my awful work—a blinky wet red eye is what it looked like to me. A pretty thing, really. The little white cavalry mother wanted my mother to whip me right then and there. My mother only said, "They're kids. It's done with. Natalie knows what she did." To this day, I am still confused—what did my mother mean? Option A: Natalie knows she has done a bad thing, and this knowing is punishment enough. Option B: Natalie has won. She has defended the corner of the street. For as long as your little white cavalry son has a scar on his chin, she will win. Natalie wins and wins. Natalie wins forever.

Technical Stuff

In a book review of When My Brother Was an Aztec, the reviewer notes "Hand-Me-Down Halloween" as one of the few poems in the collection that makes any "exciting typographical moves." She is referring to the use of forward slashes in the poem (and also to an absence in my work of exciting indigenous poetic moves such as backflips from one war horse to the next and writing concrete poems in the shape of sacred eagles or windblown braids). But in reference to the forward slashes, they aren't meant to be exciting. I hope they make the readers' eyes uncomfortable, that they physically and musically express the disjointed, jagged experience explored in the poem.

The text within the slashes can be removed but is responsible for the fractured experience. I've had people ask me, "Well, how am I supposed to read the slashes?" I usually just answer, "Yes," which I realize is no answer. Then, they realize it's no answer. It's downhill from there—ultimately, the asker ends up revealing that their great-great-great-something is an Indian princess.

Conclusion

My brother was Dracula and I was Tonto far longer than we should have been allowed to trick-or-treat. Back in those good old days of Halloween youth, we were the only Indian vampire (everyone now knows that all natives are werewolves) and Indian-fake-Indian "Up On The Hill." I often ask my mom why she let me dress up as Tonto. She just laughs. To add to the insult, my father reminded me that "Tonto" means dumb-dumb in Spanish. Perhaps I became a writer the very night I became an Indian dressed as a fake Indian named Dumb-Dumb.