In Their Own Words

Rosie Stockton on “Permanent Volta, II.”

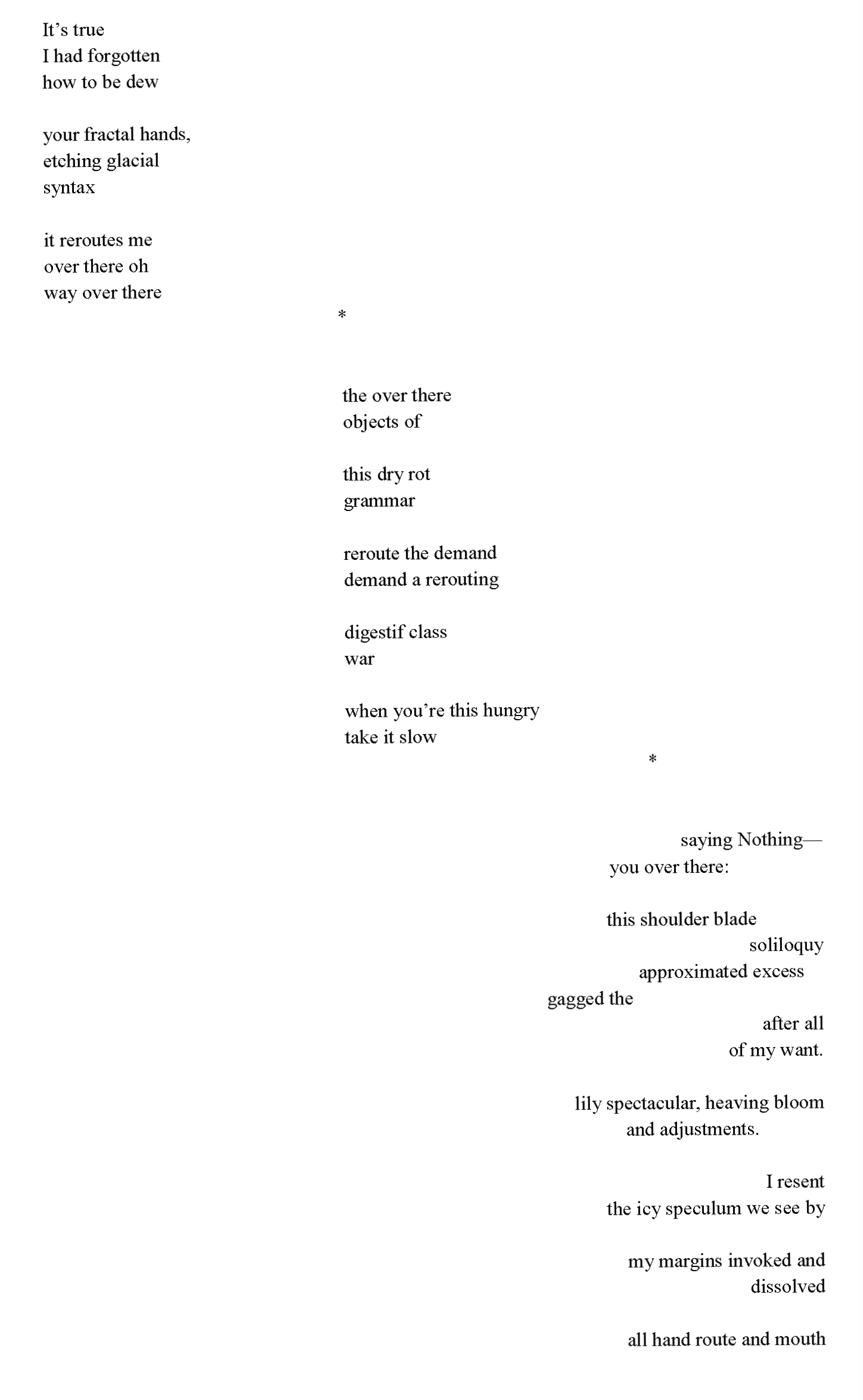

Permanent Volta, II

From Permanent Volta (Nightboat Books, 2021). Copyright © by Rosie Stockton. Reprinted with the permission of the poet and publisher.

On “Permanent Volta, II.”

In Permanent Volta (Nightboat Books 2021), I wrote crowns of sonnets, and then I dismantled them, one by one. What emerged was a series of poems about the forms we find ourselves living amidst against our will – the couple form, the nation state, the value form, the gender binary. I exercised these social contradictions in a notorious literary form associated with both colonial and romantic conquest: the sonnet. I wrote in search of the modes of love, sex, and care that persist none-the-less. Using the edge of the form as the necessary wall to thrust against, I propelled myself in excess of what the form hoped to contain.

This is one such poem originally written according to the strict constraints of the sonnet form: 14 lines, iambic pentameter, a volta, and a final couplet. Here it appears as a deconstructed sonnet that torques its way down the page, tacking with the wind and its absent origin. There are the ghosts of rhyme and of rhythmic feet, but now they are enjambed beyond recognition. From a dewy condensation on the pane of the sonnet, to a haunted flooding of form.

While writing this series, I delved into the history of the sonnet as a literary form to understand the pre-history of romantic love and all the domination and exploitation it entailed. The sonnet was invented a century before Petrarch, by a royal court lawyer named Giacomo da Lentino who added a sestet to an octave previously belonging to the strambotto

tradition, a popular Sicilian peasant song. The first octave sets up a problem – oftentimes unrequited love – and solves it by a turn inward in the final sestet. The addition of the meditative courtly sestet to the peasant’s choral octave marked a break in the nature of both performance and form. The volta away

from the popular 8-line song to the remote courtly sestet marks an inward, silent, individualizing turn: from the singing commons and into the musing self. From the oral to the written, from the communal to the individual. As the flow of labor and goods, so the history of the sonnet.

I wrote this poem in the service of sabotaging romantic love’s best form. Yet, I couldn’t abandon the form altogether. The strict constraints of the sonnet were useful and generative in coming up against my own desire for romance, friendship, and collectivity. I wanted to make felt just what forms of life it invisibilized and disavowed in collaboration with the raced, sexed systems of domination I live under. At each volta, I gathered glacial velocity to refuse the meditative turn into a separable self: in order to love over there, outside the borders of the sonnet, outside the constraints of the couple form. I wanted to say Nothing, invoke only excess, only what could exceed being said. To refuse what could possibly be distilled as measurable information, only legible in the wake of the buried violence that links premodern dispossession to the alienation of late racial capitalism, etched in our common grammars and syntax. I wanted an inefficient sonnet: edging its desire for closure, in order to feel desire at all.

I wrote to desire better in these haunted forms, to make demands of them and to find ways to make demands of each other. Invoking ecologies rather than individuals, I used the volta’s persistent torsion to bloom beyond state romance, into love’s communal insistence.