In Their Own Words

Rebecca Morgan Frank on “Monk Automaton c. 1560”

Monk Automaton, c.1560

I.

Looking at you now is like

seeing a god or a king

naked and starving in a field.

Stripped of your Damask robe

and wooden limbs,

you’ve been skinned

to the iron spine that stems

your clockworks

to your cracked face.

This is when you

are most mortal.

II.

You could hold him

in both hands, a key-turn

spiriting a clock-work miracle:

each supplicant kneeling

to his absence

of breath, blessed by his cams

and levers, the secrets beneath

his robes. Mea Culpa.

Mea Culpa. Mea Culpa–

his poplar jaw drops prayer, shuts

in a wooden-cross kiss

as his right hand beats

the absence of a heart.

He wears the face of St.

Didacus, the tripod wheels

of Hephaistos. Son

of the gods, father of the future, (couplet continues, next page)

the monk almost floats.

III.

Robots can do almost anything you please.

They are up on sexual favors, cordless vacuuming,

and martyring themselves by bomb.

Less effective at deep tissue massage; excellent

at listening to senior citizens. Working on

parking your car.

What the future brings is nothing we haven’t seen,

this quest to be little gods and make

what will do our bidding.

The medieval monk who doled out benedictions

arose from a ruler’s dream

and was then fathered by a clockmaker.

The real monk now sits alone

in the back room, smokes a cigar, enjoys

a glass of whiskey–

he’s outsourced the job.

The real monk is on the dole.

The real monk is waiting in the parking lot

for offers of day labor.

The real monk is unloading boxes at Costco.

The real monk sits in the factory,

building himself by hand.

From Oh You Robot Saints! (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2021). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “Monk Automaton c. 1560”

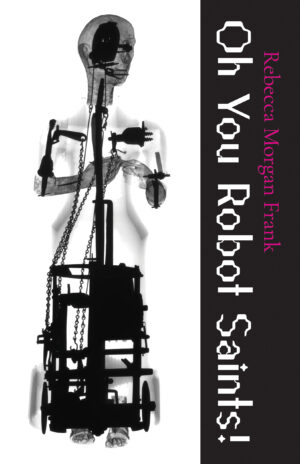

I can’t recall where I first saw a photograph of the 16th century automaton monk that inspired this poem, and who now lives, in bare x-ray form, on the cover of my most recent book, Oh You Robot Saints!

My earliest notes for the poem, found in an email to myself, include “the robot can do almost anything you please” and “the future holds nothing new–the mechanical monk could say the benedictions, leaving the human in a solitary room with cigar and a stiff drink.” From the beginning of my book project, automata provoked questions about automated labor. What could a robot do, and what would we want it to do? What becomes of humans if the things that define our humanity are enacted by robots, whether they are building bombs or physically caring for others? And what does it mean that automata, and now robots, have been used for practices that would seem to be particularly unique to humans–praying and blessing?

My first poem draft on the computer is dated a month later and begins “The monk floats” and ends “Who needs the body?” By this time, I had seen a video of the monk in action, gliding across the floor as he beat his chest and raised a cross and opened and closed his wooden mouth. At first, he wears a friar’s robe, and then the film cuts to him with his robe removed, his mechanical parts exposed. I began to consider what it would mean for priests to no longer have human bodies.

Later, on the Smithsonian website, I would find photos in which not only is the robe removed, but so is the outer shell of the monk’s torso: he is now a long iron figure, almost reminiscent of a Giacometti figure emerging from a base mechanism. Other photos take us even further inside of him; x-rays reveal the inner workings of his head and body. The effect is beautiful and somehow unnerving, reminding me how automata serve as visual metaphors for our quests to understand ourselves. What are we below this flesh? What might you see at our core?

When I finally met the monk in person, he was in a glass case at the 2017 Robot exhibit at the Science Museum in London. He was still. He could not bless me, and I could not, of course, wind him up or touch his wooden face. The human body becomes fragile and dies; an automaton becomes fragile, and, if not obsolete, lives on as an artifact to be preserved. Overuse of automata risks wearing down their mechanisms. And so the monk lives on, unable to move or bless or pray save for in his past actions, caught on YouTube or in histories or poems.