In Their Own Words

Sawako Nakayasu on “Girls Inhabit Arch”

GIRLS INHABIT ARCH

One girl’s lips tremble mountainous. One fears the loss of delicate facts. One slides right off. One leaves a fingerprint in my eye.

Here is what I know for sure.

One girl is a gift. One girl is a city. One girl is a city visiting another city not itself. One girl is sadness. One girl is a well.

The hat styled with pigeon wings is not a girl. I’ve told you this before. The girl walking nonchalantly through the streets of a European city is not a girl, unless there is a bat. The girl too full of walks, of women, of sights, comes to pause under the arch.

I mix think female all the time. I shook-hot your fat into mine. I arch you to the tender touch, that was a burn. I statue my limits into a marble female gaze. That is to say, I am looking at you. You look for a door. We are outside. O, we are out.

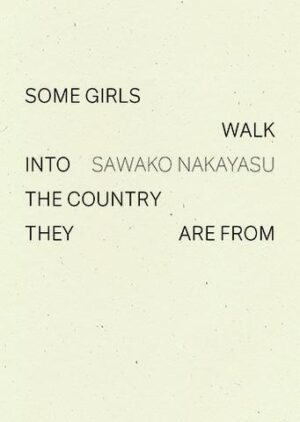

From Some Girls Walk Into the Country They Are from (Wave, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

On “Girls Inhabit Arch”

I wrote this book in serial form, as I did with two previous books, Texture Notes and The Ants. For me it’s less about the output – it’s more like a form of the mind, or a filter – in the inchoate space before the poem is actualized. A conceptual, procedural form. I’ve moved this way through texture, ants, and now girls. But texture is slightly abstract, and ants are non-human. Using girls as my conceptual form is more slippery. Girls are human, and I have once been a girl. It’s harder to say “girl” and not have you take it literally. Whereas in my mind, their role as poetic-conceptual form is not so different from texture or ants, especially when it comes to the distances held by metaphor.

I use the word “girl” or “girls” (or a variation, sometimes in other languages) over 700 times in this book – sometimes they are girls (or women) literally, sometimes they’re a mask. Or path, or intermediary. Feminism is a language I speak, and certainly the pandemic has put a new spin on my feminist sensibilities, but the most relevant fact is that this is the book I wrote as I prepared to, and then did, in 2017, return to “my country,” the US, that was being run by a white supremacist, to a country inhabited by almost 63 million people who voted for him. To live among people so comfortable with a leader like that is something to reckon with.

One day I’ll write that other book that precedes this book (temporally in life), about how I went to Japan in 2002 as a cis, straight, white-washed Asian-American, and returned 15 years later, recalibrated in racial and sexual orientation. For now, this book documents this moment of hard return. There are plenty of, um, feelings. The woman “walking nonchalantly through the streets” is Pipilotti Rist and Beyoncé. And me. But my bat looks a little different. The poem also traces through a poem called “The Arch” by Patricia Lockwood. The arch, the cities, the burn, the tender touch.

There are a couple of “arch” poems in the book. Where I work and teach, there is an arch one can pass under to symbolize membership in the community. It demarcates the point of entry, marking the inclusion (and thus the implicit exclusion) as a literal, physical, act. You enter when you matriculate, exit when you graduate. It’s where you pose for photos. In 2017 on the first day of school, members of the Pokanoket tribe, demanding the return of their land, sang and danced on the outside of that gate as the procession of incoming students passed under that arch.

Arches are not habitable. On the other hand, the spaciousness of being out, or inhabiting space both inside and out, is spreading.