In Their Own Words

Tom Sleigh on “What I Can Say in 2021 About a Famine in 2011”

What I Can Say in 2021 about a Famine in 2011

I said after watching a goat climb into a huge cooking pot and lick it clean, The war is over—but the goat said, Another one is starting—

I said after he said that he kept his trousers rolled to keep his cuffs from touching dirt, The city is divided green zone red zone but there’s nothing red or green about it.

I said, I’m dead. Good riddance, fuckhead, half-joking.

I said, and half meant it, I threw off death, I put my bones back together.

I said, Rembrandt painting Moses smashing the tablets of the Law channels the nearsighted wrath of a bony billy goat lunging on his rope.

I said, I tangle my horns in a thicket.

I said what Mrs. Nfumi said the day we saw a tiny one-room schoolhouse afloat in a flooding creek, This is what happens when hunger is what is.

I said, The way that kid held out his hand to me, forefingers and thumb pinched together, calling out, “American American . . .”

I said, It’s your turn to wait night after night like the boy sitting in his plastic chair as all the other kids gather under the tent.

I said what Isaac didn’t say, There’s no father with a knife to cut my throat.

I said, There’s this other kid who said how he and his friends like to play cards and since there aren’t any cards the cards are invisible and they slap them down hard, arguing, laughing, on high alert all afternoon for the card that breaks the game until it’s time to stop playing and get your rations.

I said what one Kenyan soldier said, Why wouldn’t Adam in the Garden hide from God if all God was doing was checking to see if Adam had fucked up?

I said, Jab me with a needle and squirt an eyedropper of vitamins down my throat.

I said, I woke to a spider crawling across my wrist.

I said, Here they come from the Grease Pit Bar, an embassy of ghosts who never again will have to turn the other cheek.

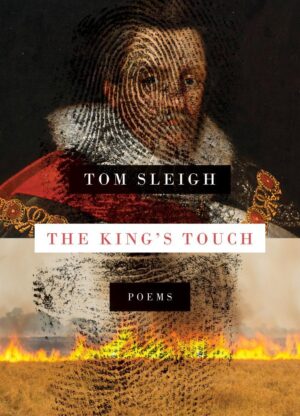

From The King's Touch (Graywolf Press, 2022), All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the poet.

On “What I Can Say in 2021 About a Famine in 2011”

Ten years ago I wrote an essay about witnessing a famine first-hand in East Africa. Most of the people who died were from Somalia—more than a quarter of a million people, half of them kids under the age of five. Of course, a statistic like “more than a quarter of a million” means nothing to anyone—it’s hard to wrap your head around such a number. But if you imagine every man, woman, and child starving to death in the city of Buffalo, say, then you begin to understand what it would mean: everybody in your building, your block, your neighborhood dead.

I’m not going to rehearse my essay point by point, which appeared in The Land Between Two Rivers: Writing In an Age of Refugees. All I’ll say is that when you see hundreds of starving people coming in to a refugee camp over red drifting sand, shoulders bent under grain sacks carrying their few possessions, some pushing wheeled carts, the lucky ones in buses so overcrowded that people are clinging to the roof, you realize how individual each person’s suffering is. “Famine” doesn’t begin to connote the misery and desperation, or resilience and grace, of human beings on the edge of starvation. Drought, desert hardpan, hot sun; food convoys blowing tires and snapping axles while aid workers are shot, kidnapped, beaten; rival militias stealing food or banning distribution while geopolitical foes impose restrictions so that aid bogs down or disappears into legal and administrative sinkholes; everywhere and always, large and small, the causes and calamities pile higher and higher in an ever growing mountain of wreckage.

That’s how it looks from close up, anyway. But that kind of visceral response inevitably gives way to finding solutions to “the problem.” Let a decade go by, and suddenly that mountain is completely fogged in by “policy speak”—the necessary, but bland abstractions (“lack of access” “donor-funding mechanisms”) that can distance one from the physical immediacy of seeing people starve.

But a year or so ago, perhaps sparked off by the widespread suffering caused by Covid, the famine again imprinted itself on my nervous system. Suddenly, fragmented images and surreal dreams of emaciated bodies began to surface of themselves. And the voices of people that I’d spoken with, who’d told me what the famine had taken from them—husbands, wives, children, goats, camels—echoed and re-echoed with ever greater intensity. And that’s when the form of the litany announced itself. But the voice saying over and over “I said” wasn’t me, or a “me” I completely recognized. Yes, the voices were voices I’d heard, but they’d wrenched themselves free from 2011, and now welled up in a cacaphony, each striving to enter the poem on its own strange terms.

The goat I’d seen climb into a huge cooking pot, so it could lick up the remains of a meal cooked for starving kids, could now talk back, refute and complicate the feckless observation that the war was over. Then the goat allowed Abraham and Isaac to enter the poem, but the goat refused to play along with Abraham’s God, and rejected His logic of sacrifice. Or in the Grease Pit Bar, Patrice from Burundi, an African Union soldier I traded rounds of beer with, turned into a kind of anti-prophet by defending Adam and Eve when they hid from God in the Garden of Eden. Paradise and Hell, the realm of the unconscious and the realm of statistics, the dead rising as avengers or zombies or vaguely seen shadows, kids playing imaginary card games, conversations I had with NGO workers, all these images shook off my prior assumptions and began to take on a new shape—a shape less tied to the day-to-day and more grounded in a rebelliously oneiric understanding of that decade-old suffering.

But one image, no matter how I tried to incorporate it, refused to work itself into the poem—so I’ll write it down here as something that haunted me then and haunts me now.

The sun pours down on a burned-out tank on the crest of a sand hill, its rusted-through armor plate so pitted with peepholes that when I put my eye to one of the holes, what looks like a scorpion living inside the tank scuttles away, its stinger arched over its back. As my eyes adjust, I can see that the tank bottom has flaked and scabbed into hills and valleys of rust, while little spirals of dust float in the shafts of incoming light.