Q & A: American Poetry

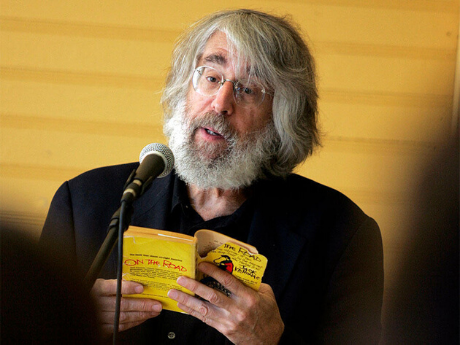

Q & A American Poetry: Lloyd Schwartz

Are there essential ways in which you consider yourself an American poet?

Yes. Especially since my particular approach to writing poems over the past couple of decades has primarily concerned itself with the incorporation of idiomatic, spoken American English: monologues and dialogues (people— characters— literally talking aloud, either to themselves or to each other, or "talking" to the reader); or narratives that incorporate bits of dialogue. It occurs to me in answering this questionnaire that it's very important for me to think of myself as an American poet, to be a writer making a contribution to American poetry. And my own dramatic monologues and dialogues have encouraged me to use a more conversational English in the poems in my own voice. Perhaps the very idea of "voice" in lyric poems (Elizabeth Bishop especially comes to mind) is an especially American way of thinking about poetry. Which may be why poetry readings (including slams and "performance" pieces) have become such a large part of the American poetry scene.

Besides language itself, my subject matter, too, has to be "American"—that is, looking at where I live, at this entire country, and at the world from a distinctly American point of view. Even my poems about traveling abroad come from the starting point of American self-consciousness (or semi-self-consciousness— influence of Henry James?). Writing about contemporary life, how can one be other than American? Specificity of detail itself—"realism"—seems a particularly American phenomenon in poetry, the assimilation of techniques from the realms of fiction and drama (especially movies—which have looser formal structures than plays—poetry can be even more "cinematic" than film.) "Confessional" poetry—the desire to write directly about the most intimate personal situations (rather than just intimate "feelings") also seems a peculiarly American impulse. But I also think of Robert Hass describing Robert Lowell's poems not as "Confessional" but as "Family Poems," in the tradition of Eugene O'Neill (rather than Emily Dickinson or Whitman), has a particularly American resonance.

Which brings me to my uses of—often conscious departures from—traditional form, which also has a particularly American aspect. Free verse itself has by now become a deeply ingrained way of writing about American life (as opposed to late-19th-century French vers librewhich was probably used more as an escape from Realism). Gail Mazur has coined the term "American sonnet" for the kind of unrhymed, free-verse 14-line poem Robert Lowell wrote for so many years. The freedom to write a sonnet without rhyme or meter, that consciously reflects a departure from these as well as from the traditional structures of Shakesperean or Petrachan sonnets, yet is also determined to think in 14-line units seems a uniquely American way of dealing with tradition (or like Elizabeth Bishop's "Sonnet," which consciously inverts Petrarchan proportaions, uses short lines, and teases our expectations about where the rhymes are going to come).

And tone. Cheekiness. Humor. Jokes. Perversity for perversity's sake (that is, to write against the grain of assumptions about what poetry should be). I don't want my serious poems—my mostserious poems—to be lugubrious.

When you consider your own "tradition," do you think primarily of American poets?

In terms of incorporating spoken language into verse, I see a longer perspective. How could I use voices and the idea of characters speaking without ther ehaving been a Chaucer, Shakespeare, or Browning? Then there was Robert Frost. More immediately, the idea of "a mind in action" clearly owes a big debt to Bishop and Lowell, yet Keats's Odes have probably been the greatest influence on my own sense of the way lyric poems can be dramatic, that is, how they can end in a place different from where they began.

Do you believe there is anything specifically American about past and contemporary American poetry? Is there American poetry in the sense that there is said to be American painting or American film? Do you wish to distinguish American poetry from British or other English language poetry?

No question. No question. No question. (See above.)

Which historic poets do you consider most responsible for generating distinctly American poetics?

Whitman: breaking the rules

Dickinson: twisting the rules; and a new level of immediate, domestic, close observation

William Carlos Williams: for consolidating an "American" language

Frost: incorporating American speech into traditional forms (blank verse, quatrains) and beginning to "liberate" the forms themselves in the process.

What import does regional poetry occupy in your sense of American poetry?

Complicated. In an obvious way, local subject matter, like landscape in a good deal of Western poetry, and certain regional issues, like the ramifications of the Civil War, for example, in a good deal of Southern writing. Yet the best Civil War poem is Lowell's "For the Union Dead"; and the best poem on the issue of the human relation to nature is probably Frost's "The Gift Outright." So there's a lot more fluidity in what "regional" can be. There's also a looser kind of regionalism in just the common situation of poets who are friends responding in different ways to similar issues.

What significance does popular culture possess in your sense of American poetry?

Major. Maybe one of the defining qualities of contemporary American poetry is the pervasive and comfortable inclusion of references to and influences of popular culture, especially pop music (both as a reference point and as a stylistic influence), movies (not only as points of reference but as having a big influence on the structural fluidity of American poems), television (the way contemporary culture comes directly into our homes), and the daily news.

What about the American poets who lived primarily in Europe (Eliot, Pound, Stein)? What about the European poets who have recently lived or worked in America (Heaney, Walcott, Milosz)?

Anything that brings us closer to the world or the world closer to us is a great thing. Seamus Heaney has probably been the most important poet who has raised our consciousness to the subtlety of distinctions necessary for good poems on political subjects (but he may also be the most important European poet to be influenced by American poetry.) Clearly some American poets—Mark Strand, Charles Simic—have continued to play an important role in connecting us more to international influences. Abstraction and Surrealism, it seems to me, have largely been the internationalization here of European tendencies. It's probably not a coincidence that the term "avant garde" is not in English, though Americans living abroad have been major forces in the avant garde.

Are you interested in poetry written in America but not in English?

I haven't been. Exposure has been one problem. But since reading poems in a different language involves translation, my tendency leans more towards world poetry than poetry written in other languages here.

Are you more likely to read a contemporary non-American poet who writes in English or a contemporary non-American poet translated into English?

Translated.

Do other aspects of your life (for instance, gender, sexual preference, ethnicity) figure more prominently than nationality in your self-identity as a poet?

Probably not more prominently, though gender, sexual preference, ethnicity, and class have played important roles in my poems, which may be another reason to think of them as "American" poems. In fact, my tendency not to identify with any group, may be yet one more reason to identify myself as an "American." If anything, it's this questionnaire that has most made me think of myself as an "American poet."

Do you believe you could readily distinguish a poem by an American poet from a poem by other poets writing in English?

Probably. Unless a given "other" poet was specifically—and especially successfully—imitating American styles and attitudes.

What do you see as the consequences of "political correctness" for American poetry?

Disaster. Death. American poetry (I'm looking back to Dickinson and Whitman and remembering Ginsberg) is founded on impulses of freedom, rebellion, honesty, saying what one damn well pleases to say. Political correctness has led to one of the most dangerous forms of censorship—self-censorship—which is a form of fear. Poets simply can't afford to be timid or fearful in their poems. Though political correctness has encouraged some degree of sensitivity to the feelings of others, which is its one positive effect, better to put up with, be appalled by, or laugh at narrow-minded prejudices than straight-jacket anti-social poetic behavior.

What are your predictions for American poetry in the next century?

Prayers more than predictions—an optimistic prayer for the health of poems, because along with all the schlock there are so many wonderfully fresh and original voices writing today. Fear that the melodramatic and sentimental oversimplifications of much "performance poetry" will drown out the quieter, more complicated, more subtly insidious and ironic (i.e. realistic) voices.

Published 1999.