In Their Own Words

Shira Dentz on “Sisyphusina”

So tired, rocks settling in back of my eyes. Bone particles

of sand + flat, smooth black rocks + a waterfall = a Zen

garden. But not calm. Immeasurably loaded.

Flat, smooth rocks and a waterfall. Black vultures fly so

high in southern Africa, tradition says they see the future.

Immeasurably & loaded like Dickinson’s gun. A vista

crawls through dugouts, or (depending on the observer’s

position) pillows, of gray static.

Vultures fly high. Want to sit this one out. Matter crawls

through pillows, gray. Listen to wind’s changing seasons:

winter wind, springwind, summer’s wind, fall.

I want to sit. Sleep the color of iron, pressing in-between.

Wind, a new season, paws at tree branches. Vultures use

gravity as a tool, dropping bones to the ground to crack

open their marrow.

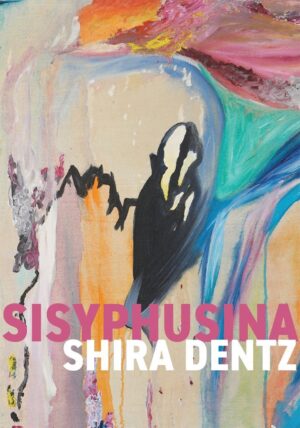

From Sisyphusina (Pank Books, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

This poem was the first “Sisyphusina” poem I composed for my book, also called Sisyphusina. Two other poems called “Sisyphusina” grew from this one and appear at different points, nonsequentially, in the book. So this poem is an origin poem, though it’s not the first poem that I wrote when I began working on this book. Its methodology was spurred by a constraint that a fiction writer friend gave me when I was blocked during the first year I worked on this collection, which I had tentatively titled Rose Secoming. I had coined “secoming” as a neologism to encompass “becoming” and “succumbing,” two dynamic processes, or directions, that occur within female aging. The “rose” has been a consistent emblem of feminine beauty from at least the middle ages through the present, and I posited “secoming” in relation to this rose. One might jettison the antecedent “feminine” in the previous sentence, as an ideal of physical beauty and female worth have been and are often inextricably tied in many contexts, settings, and time periods.

Back to this poem’s origins: I don’t remember whether I titled it “Sisyphusina” before or after I wrote it, and either way I had no thought of writing more poems with this title nor did I think that it could be a good title for the entire work—this would occur to me years later. Among the things that were significant about this poem, looking back, is that its composition was in essence both a constraint and a collaboration—my friend’s’ prompt and what I did with it. The reason I note this is that the collection contains other collaborations — between myself and visual artist Kathline Carr, video artist Kathy High, and the late musical composer Pauline Oliveros. The collaborative nature of this book is expressive of its collective “skin” embodying a voice of female aging.

Collaboration and constraints are key in other ways in this book. For instance, the book juxtaposes my own particular story within the context of the personal constraints I inherited with the collective story within the sociocultural landscapes that shape and perpetuate gender roles and identities that many of us inherit. These sociocultural landscapes include influential writers and artists to whom I allude in my texts, ancient and contemporary fashion worlds, advertising, myths, and pop culture. My research for the book expanded into life and animal sciences to draw further perspective on female aging as part of my meditation/inquiry into this subject. The poem “Sisyphusina” was composed as a collage that braids fiction, autobiographical details, scientific observations, transnational history, and myth, as well as formally braiding prose and poetry; likewise, the book is a hybrid of prose, poetry, and visual elements; it also contains a musical composition accessible via a QR code at the end.

In retrospect, the process of writing this poem and the poem itself gave birth to this book’s title. Not only do I identify as a feminist writer, attempting to give voice to aspects of female experience that have been more or less silent, but my equal-opportunity side wanted to fill in an existential omission. Now there’s a female Sisyphusina. I understand that I risk encroaching on binary gendering here, so want to state clearly that I aspire to contribute to awakening parts of a psyche that may not have received as much light. “Sisyphusina” also sounds like a pop figure’s name to me, funnily and paradoxically a heroine-type.

My own history has been impacted by sexual violation—scarred, marked. The loops between the personal and the social in terms of gender and sexual identities is part of what I wish to bear witness to as a writer/artist. Of course, the personal includes family history which can’t be divorced from social, economic, and political forces—these narratives intertwine. Perhaps this poem is haunted, too, by the roots of what gave rise to this collection. Many writers have noted that writers write the same thing over and over again, hoping to get it “right.” Surely, there’s a Sisyphusean aspect to being an artist then. Sisyphusina is a female apparition, a sprite.