Tributes

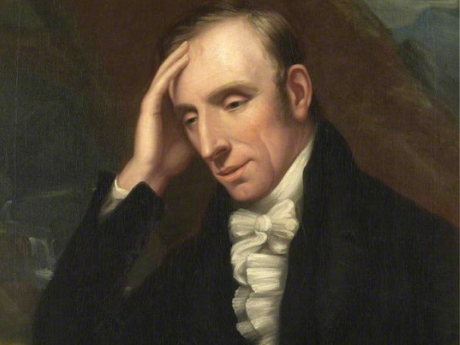

Eavan Boland on William Wordsworth

I've always believed there are certain pieces of writing which are magic doors in locked houses. Just as we think we'll never get entry, never be able to go in, this one door springs open at our slightest touch. And after that we can come and go as we please. Wordsworth's "To My Sister" is one of these and one of my favorite poems. It is modest, quirky, and off the beaten track, a poem that goes along at a companionable walking pace—conversational, talky, and apparently throwaway. But appearances are deceptive. For all its downright reticence, this poem shines a challenging light on one of the most troubling aspects of Romanticism, one of its most problematic inheritances: in other words the corrosive history of the Sublime.

Although the idea may be as old as Longinus, at this moment in history it had a particular power. In the late 1740's, some fifty years before the poem was written, the critic John Baillie wrote that "vast objects occasion vast Sensations and vast sensations give the Mind a Higher Idea of her own Powers." In Edmund Burke's "Philosophical Treatise into the Origins of our ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful," written just forty years before this poem, Burke defined the sublime as what appeared greater than us, what we therefore feared and were awestruck by—whether landscape or literature. At a moment when the claims of the un-rational mind were just beginning to be celebrated, these ideas gained a widespread currency. Critics and philosophers began to define the sublime as a system which challenged the inner world of man to equal the outer one, challenged sensibility and imagination to construct an inner lexicon which reflected the grandeur of these outer sights. The idea of grandeur, both in language and landscape, began to change the scale of the poem and the ambitions of the poet. Modesty was no longer a virtue. And that makes "To My Sister" all the more remarkable. "To My Sister" shows Wordsworth in a light that in some ways is uncharacteristic: as a poet, in other words, intent on disciplining the sublime rather than deferring to it.

The poem was written early in the year 1798, when Wordsworth was living near the beautiful Quantock Hills in Somerset. It was a year of change, of widespread upheaval. A bloody unsettled Europe stretched to the east, the fiery aftermath of the French Revolution. The clicking and swooping of the guillotine could still be heard, albeit in memory, even across the Channel. And even in the quiet part of England where Wordsworth lived, there were fears of a French invasion. Only a few months earlier, there had been reports that the Dutch Fleet was ready to bring a French invasion force to England.

Into this time of unrest and suspicion come Dorothy and William Wordsworth, a young man and woman, with strong ties to France. They had come to Somerset for this one year and were living in a beautiful house called Alfoxden Park near the Quantock hills. William was twenty-seven and Dorothy twenty-six. And they brought with them a child, Basil Montagu, the son of their widowed friend. They were taking care of him during these years, and he has a wonderful, walk-on part in the poem, although under a different name.

Alfoxden Park was a long, low house with a view on its north-eastern side to the Bristol Channel. It came at a peppercorn rent, because it needed habitation. It was also beautiful and spacious. Dorothy would remember this all her life as a location of a special happiness. "There is everything here," she wrote to a friend, "sea, woods wild as fancy ever painted, brooks clear and pebbly as in Cumberland, villages so romantic; and William and I—in a wander by ourselves—found out a sequestered waterfall in a dell formed by steep hills covered with full-grown timber trees." Imagine how they must have looked: a young man and woman who spend their time out of doors, are unfashionably tanned and walk the countryside at all hours of the day and night. Not surprisingly, their neighbors are deeply uneasy about them. One wrote that Wordsworth must be "A French Jacobin for he is so silent and dark."

It was in Alfoxden, in this spring of 1798, that Wordsworth's long and wounded depression began to heal. He had left France—and his mistress and his child—years earlier. With hindsight we can see that his sympathy with French radicalism was not just a politic but also the shadow of his own deep conflicts about order and disorder. The conflicts had injured him. But here in the rural quiet of this part of England, his spirits began to heal. Over and over in the cold spring weather he walked the road between Nether Stowey where Coleridge lived and Alfoxden. Here on this road, in the conversations at their destination, the poems began to arrive which made the brilliant, surprising, and disruptive volume of the Lyrical Ballads. And this was where, occasionally, Wordsworth would read his poems aloud with a fierce intensity. Hazlitt, who was once there for such a reading, said, famously, "whatever might be thought about the poem, his face was a book where men might read strange matters."

To My Sister

It is the first mild day of March:

Each minute sweeter than before

The redbreast sings from the tall larch

That stands beside our door.

There is a blessing in the air,

Which seems a sense of joy to yield

To the bare trees, and mountains bare,

And grass in the green field.

My sister! ('tis a wish of mine)

Now that our morning meal is done,

Make haste, your morning task resign;

Come forth and feel the sun.

Edward will come with you—and, pray,

Put on with speed your woodland dress;

And bring no book: for this one day

We'll give to idleness.

No joyless forms shall regulate

Our living calendar:

We from to-day, my Friend, will date

The opening of the year.

Love, now a universal birth,

From heart to heart is stealing,

From earth to man, from man to earth:

—It is the hour of feeling.

One moment now may give us more

Than years of toiling reason:

Our minds shall drink at every pore

The spirit of the season.

Some silent laws our hearts will make,

Which they shall long obey:

We for the year to come may take

Our temper from to-day.

And from the blessed power that rolls

About, below, above,

We'll frame the measure of our souls:

They shall be tuned to love.

Then come, my Sister! come, I pray,

With speed put on your woodland dress;

And bring no book: for this one day

We'll give to idleness.

— William Wordsworth, 1798

And so it was here in this blessed shelter of Alfoxden that Wordsworth wrote "To My Sister." A few years later in his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads he would argue that a poet was "a man speaking to men"—in other words that the poem must happen in a human voice, in a living dialect. After an ornamental 18th century it was a radical idea. Here is a place where that voice—and that vernacular ideology—can be heard in all its first, flamboyant bravery, and yet the theatre of the poem is deceptively modest. The scene is a March morning, the occasion is the mild, south-wind weather of an English spring. All he does is ask his sister to take her warm cloak, bring the child they were caring for with them—here he calls him Edward—and just take the day off. Nothing more than that. And yet the poem, which starts out with this mild invocation—which is talkative, casual, and almost invites its reader to be an eavesdropper—manages for all that to become a map of a shape-shifting new era in poetry.

This poem belongs to a group of four written in this spring. The others, "Lines Written in Early Spring" and "Expostulation and Reply" and "The Tables Turned" all share this quality of ordinary exuberant dailyness and belong to the magical quiet of Alfoxden. I admire this poem extravagantly for its freshness, for its advocacy of the ordinary, for its address to a woman that includes her in the human business of the poem—rare in that day of ornamental love poetry. In a way, however, these are secondary admirations. I admire it especially for its refusal of the sublime. No one could say that the sublime is altogether missing from this poem. The huge ideas of a natural order and the ordering of the natural are all evident. The signature claims of early Romanticism—that the heart can make "silent laws," that instinct can triumph over "toiling reason," that nature is the true text—are also here. But they are rooted, tied down, made to come to earth, made to stay only at the height of the eye-level human ordinary. This is a position paper for the everyday world. No one who reads this poem about a woodland walk can doubt that once it was finished that woodland walk really took place. No one need doubt that William and Dorothy went out into the early spring sun of Somerset and did indeed give that one day to idleness.

In Wordsworth's late poems—although I think his great poem "The Prelude" casts a cold light of irony on it— the sublime becomes a feature of his work and gets deeply woven into the poetry of the Romantic Movement—so much so that Keats rather impatiently refers to Wordsworth's "egotistical sublime." But when I think of the place of the sublime in the Romantic Movement, I think wistfully not so much of the Wordsworth of "Tintern Abbey" or of the "Ode on the Intimations of Immortality" as of this blessed, daring poem to his sister where his own fresh and confident north of England voice can be heard so clearly.

The sublime seems to me a foreign import into this wonderful, radical, poetic movement that Romanticism was—at least in its inception. The poet of Alfoxden, who asked his sister to go into the woods, was not a natural seeker after the sublime. He was not in pursuit of the "vast sensations" described by John Baillie. He was a thorough-going radical, a witness to two revolutions, the French and the Industrial, an ardent supporter of the first, at least in the beginning, and a bitter opponent of the second. He was the seeker out of the Leechgatherer, of the Pedlar, of the woman who lost her son at sea. He was the witness, commentator, and elegist of the ruined pastoral world of post-Industrial England. And he was therefore, all the more plausible as the pastoral poet who called for a morning given to idleness so that instinct could be healed, and the mind re-constructed.

And whenever I think with affection and admiration of this poem I think also of those poets who in our day have refused the sublime. Of Elizabeth Bishop's wayward seal for instance in At the Fishhouses—and her stubborn inclusion of him to make sure that nature stays comical, and humanly perceived. Or of Sylvia Plath's Devon nursery where even the stars are made to plummet to their "dark addresses." Or Dylan Thomas's Fern Hill where the sublime is kept firmly held at the apron strings of elegy and memory.

Four years after his time in Alfoxden Wordsworth wrote—in the glowing September of 1802—his great Preface to the Lyrical Ballads. It is aggressive, definite, defiant. It is anti-authoritarian on the very subject of the sublime. "Taking up the subject, then, upon general grounds," he writes, "I ask what is meant by the word Poet? What is a Poet? To whom does he address himself? And what language is to be expected from him? He is a man speaking to men." As it happens, in "To My Sister" he is also a man talking to a woman. But he is absolutely writing, in that poem, in the spirit of his great preface: against ornament, against the sublime, against the over-reaching meaning. If I could nominate a place, a text, a series of words as the river-mouth where are the beginnings of the wonderful, humane enterprise which early Romanticism was, it would be this poem, this morning in Somerset, this cloak hanging on a hook, and this refusal to make any of it less truthful than it was.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 2001.