Three poems by Jazra Khaleed

Visiting Poet

Visiting Poet: Peter Constantine on Jazra Khaleed

Somewhere in Athens

Somewhere in Athens December the Sixth

The kid will kill the cop before sunup

Somewhere in Athens December the Seventh

On the streets the banks are burnt one by one

Somewhere in Athens December the Eighth

Let’s cut a rug in Parliament’s rubble

Somewhere in Athens December the Ninth

The poets in the streets eulogize fires

Somewhere in Athens December the Naught

Because the rebels shot the bell-tower clocks

Translated by Sarah McCann

*

Still Life

Midday is hot. It cripples me

It’s been two days since I ate. I’m pregnant with tempest

Children don’t play in my neighborhood

Lovers don jockey caps

They are flat. Like their kisses

They are unwrinkled

They walk along the streets, elbows jutted out

News gets plastered to the walls in my neighborhood

Glee festers like a bullet in a cop’s stomach

I myself sell butcher knives at the abattoir of the everyday

I write a poem every time I go from my home to the metro

I am waiting to be touched

Translated by Sarah McCann

*

First Death of the Poet J.K.

I will die the death of an immigrant from Chechnya,

you’ll find me in the trash

with throat cut and hands cold.

On the town square they will say: May he rest in war!

And if you spread my word to the ends of the earth

I will come back as a panther one sunny day.

I will die the death of a prostitute from Senegal,

you’ll find me in some vacant lot

with a police bullet in my head.

On the town square they will say: Blessed be the warmongers!

And if you lumber me with the sins of poets

I shall rise from the ashes once again.

Translated by Peter Constantine

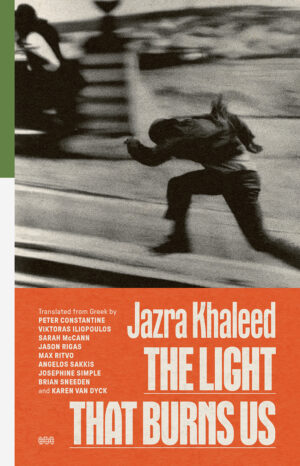

Poems by Jazra Khaleed, reprinted from The Light That Burns Us (World Poetry, 2024). Copyright © 2024 by Jazra Khaleed, translation copyright © 2024 by Sarah McCann and Peter Constantine. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Words are my Praetorian Guard.

When I give the sign they leap into the line of fire.

Whoever comes at me feels their spears.

—Jazra Khaleed

The 1990s and the first years of the new millennium in Greece were a golden era of prosperity and development. Athens, after several failed bids, was finally to host the Olympics in 2004, providing an opportunity for Greece to brand itself to its own people and the rest of the world as a nation with a glorious past, a glorious present, and a glorious future. In feverish preparation for the Games, Athens was transformed into a vast construction site, an urban redevelopment project that was called the nation’s “steam engine of economic growth.” A metro network was under construction, with spacious marble-halled stations that exhibited Byzantine and Ancient Greek treasures unearthed as the subway tunnels were being burrowed beneath the city; new highway interchanges and ultramodern freeway junctions appeared, along with new fleets of city buses, a new suburban rapid transit system, a brand-new airport that won the 2004 European Airport of the Year Award. Private and public money was being spent without limit, and Greece was prospering on seemingly endless credit.

Greece’s economic boom was ranked as one of the strongest in Europe. But all was not well. Over 20 percent of the population was living on the brink of poverty and, despite a glittering façade of success, Greece had one of the highest rates of youth unemployment, higher in 2004, according to World Bank figures, than struggling countries such as Yemen, Sri Lanka, and Zimbabwe.

The demographics of Athens were also in flux. Greece, which since the Homeric Bronze Age had been a place of emigration, a place that Greeks left for a better life elsewhere, had become, quite suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, a country to which hundreds of thousands were now immigrating. A major new resource of cheap labor was fueling the Greek economic miracle and the Olympic dream, but most of the new immigrants were not being integrated, and many remained undocumented, living precarious and desperate lives as Greece began to spiral toward extreme indigence, penury, and finally bankruptcy.

Enter the young poet Jazra Khaleed. His first poetry collection—Poems Soaked in Gasoline (Ποιήματα Βουτηγμένα στη Βενζίνη)—was electrifying, an unapologetic indictment of the wrongs faced by immigrants, by the rudderless young generation, by leftist activists in a Greece blighted by neoliberal policies of deregulation and privatization. It was now 2009; the country was bankrupt, the streets of Athens on fire as demonstrators clashed with an armed police force that pushed them back with brute force and tear gas. As M. Hulot was to write in the Athenian cultural magazine LIFO about Jazra’s poems:

They were hard-hitting, with rap-like lyrics redolent of the feral side of hip hop: razor-sharp, violent, this was the urban poetry of the late ’00s and a prelude to a new unpredictable decade that was yet to show its savagery. Jazra’s poems are the clearest forecast of what was to beset Greece after 2008.

Jazra Khaleed was unknown when he published these poems “soaked in gasoline”—to be set on fire and hurled at the establishment. Born in Chechnya in 1979, he was a poet who seemed very Greek and not Greek at all; his language was sharp, sophisticated, and controlled with elegant rhythms and contemporary street speech that often had an undertow of a sophisticated language with moments of Byzantine and New Testament Greek. In his poetry there is a power, erudition, and control that Greek readers could not equate with a man named Jazra, a poet whom no Greek literary press or magazine was prepared to publish. And so Jazra Khaleed published in samizdat, and on his blog, an unconventional move that went against the grain of the poetry scene, but which by 2010 had made him the most widely translated young Greek poet, and the voice of the new “Crisis Generation” that was coming of age in a ruined and floundering Greece.

“In a war or revolution, a poet may do very well as a guerrilla fighter,” Auden predicted in his 1948 essay, “The Poet and the City.” Jazra Khaleed has taken Auden’s challenge on. In an interview for World Literature Today in March 2010, I asked Khaleed how he saw himself “fitting into the Modern Greek picture, the modern poetry scene in Greece,” to which he said:

As a poet, I stand with all those who are trying to invigorate the Greek language, to turn it against itself, and to attack the police patrolling it. If I am part of a movement, it is one that uses poetry to launch attacks on conservatism, fanaticism, and the nationalistic tendencies that flourish in Greek society, which has the blood of immigrants on its hands.

As we see in The Light That Burns Us, his poems are testimonial: They bear witness and they indict, they give voice to the disenfranchised and the oppressed, they are rhythmic and vehement manifestos. The poems are always political—sometimes from a very personal perspective, and sometimes from that of an objective outsider and commentator. Stendhal in his novel The Charterhouse of Parma comments that “politics in a literary work is like a pistol shot at a concert:” harsh, disruptive, abrasive. The untroubled audience is rudely torn back to a reality that may well be dangerous. But if the politics in Jazra Khaleed’s poetry is disruptive, it is intentional. As Khaleed said to Max Ritvo, one of his translators, in a 2015 interview in Los Angeles Review of Books:

I see myself and what I write as part of discourse—antifascist discourse. My poetry connects to posters on the streets, magazines. All poems are written in a certain language—this language is the language of those in power. Even if one doesn’t admit it, if one doesn’t know it—the stuff we all write is political, since we use a certain kind of language. Words and similes aren’t innocent.

When we read Khaleed we are torn back to the dangerous realities of being an immigrant in modern Greece, of being a Syrian refugee, a downtrodden Greek worker whose salary keeps dwindling as indigence beckons.

Reprinted from The Light That Burns Us edited by Karen Van Dyck (World Poetry Books, 2024).

Jazra Khaleed is an Athens-based poet, translator, and filmmaker. Khaleed’s works focus on issues of working-class experiences and cultures, homeland and origin, immigration and war, and are an indictment of racism, social injustice, and classism in contemporary Greece. He has published four collections of poetry and his work is widely translated into European and Asian languages. English translations of his poems have appeared in The Guardian, Los Angeles Review of Books, World Literature Today, and elsewhere. He is a founding editor of the Athenian poetry magazine Teflon and specializes in translating political and experimental poetry into Greek. His short films have been featured at international film festivals. The Light That Burns Us is the first book of his poetry to appear in English translation.

Peter Constantine's recent translations include works by Augustine, Solzhenitsyn, Rousseau, Machiavelli, Gogol and Tolstoy. He is a Guggenheim Fellow and was awarded the PEN Translation Prize for Six Early Stories by Thomas Mann, and the National Translation Award for The Undiscovered Chekhov. He was an editor of A Century of Greek Poetry: 1900–2000, and the anthology The Greek Poets: Homer to the Present. He is Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Connecticut and the publisher of World Poetry Books.

Sarah McCann earned her MFA in Poetry at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop and now holds the Tyler Chair in Creative Writing at St. Mark’s School. She has been published in such journals as The Bennington Review, Margie, Midway Journal, and The South Dakota Review. Her Fulbright-funded translations from Modern Greek have been published in such anthologies and journals as Austerity Measures, Words Without Borders, Poetry International, and World Literature Today.