In Their Own Words

Adrian Matejka on “Love Notes”

Do you love vague commitments?

Do you love bad news in crooning shapes?

Whole or half, tattoos mooning on

conjoined ribcages? Check this box &,

like a breath, you’ll feel mostly bygone.

Like one of those early recordings, you’ll

be scratchy & demystified. Untranscribably

confessional, until the last quarter note

is a processional. You’ll be absolutely fine,

flipped to the B side of this note’s high-lined

referendum. Magnificent & stark inside

the addendum, like a big breath exhaled

through the smart part of a question mark.

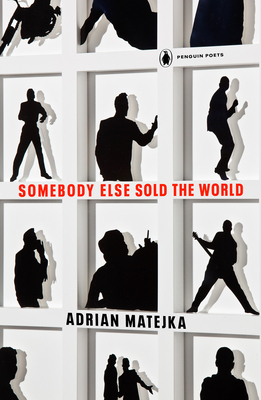

From Somebody Else Sold the World (Penguin Poets), Copyright © 2021. Reprinted with the permission of the poet and publisher.

On "Love Notes"

When I was 10, I wrote a note to Cynthia, the girl of everybody in my 4th grade class’s dreams. In my best cursive, I wrote “DO YOU LIKE ME? CHECK THIS BOX” on a lined sheet of paper from my writing notebook. I freehanded a big square for YES and another, smaller one for NO, then folded my first love poem up into a triangle to give to her.

The April sun was coming through the open blinds as Mrs. Jones stood in front of the chalkboard explaining something about multiplication in her usual plaid pants suit. I was counting the seconds like Elizabeth Barrett Browning counted the ways, and when Mrs. Jones’s back was turned to write I gave the note to Harold to give to Cynthia one row over. The timing was immaculate: each chalk stroke sounding like bird chatter as I passed the triangle and the girl in front of me giggled about something I couldn’t figure out.

What happened next is familiar. The sun retreated behind the clouds as Ms. Jones somehow made it from the chalkboard to the back row in one step. Harold said “It isn’t mine; it’s Adrian’s” before she even asked, once again earning his title as class stool pigeon. Before she sent me to the principal’s office, Ms. Jones unfolded and read my note to the class with an uppercase voice—humiliation added to detention. I got moved to another homeroom after that, one that the principal thought would be “more suitable for my romantic imagination.”

Since then, I’ve tried to deny, change, or otherwise resist my romanticism. In part because I understand that it can be effusive and a little corny at a time when irony remains the coin of the poetic realm. But, like Jack Gilbert and other poets of eros who inspire me, romanticism is foundational to my worldview and imagistic systems. I don’t mean that in William Wordsworth’s spontaneous overflow way. I mean it in the “No, for real. You are everything” slow jam and falsetto way. That moment when the singer gets fully vibrato on their way to heartbeat or heartbreak. There’s only a deep breath between the two, really.

Poets have been trying to demystify love since at least 2000 BCE and as in “Love Notes,” we’re still fumbling to find public language for a thing whose real vocabulary is private. At the same time, love poems begin with bravery, with reseeing the language and what we are willing to share. It reminds me of this beautiful quote from James Baldwin’s essay “Take Me to the Water”:

Because you love one human being, you see everyone else very differently than you saw them before—perhaps I only mean to say that you begin to see—and you are both stronger and more vulnerable, both free and bound.

“Love Notes” tries to decode some of the mystery and vulnerability Baldwin talks about. I tried as best as I could to liberate my own language, to recapture the younger, romantic me while also acknowledging that a whole lot has changed in my world of knowing since 1981. And none of this considers what might have happened if my note had somehow reached Cynthia. Would she have read it or would she have thrown into the pile of unread losers in her desk? What box would she have checked? That unknowable part of romance, the then and now of longing, is the real inspiration for “Love Notes.”