In Their Own Words

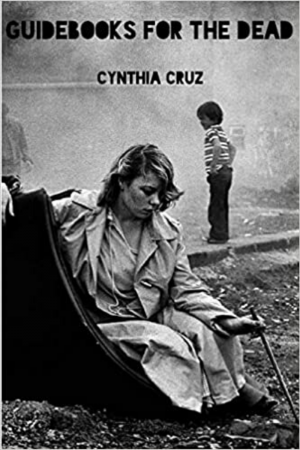

Cynthia Cruz on “Guidebooks for the Dead”

Or the beginnings of deadly illness.

I exist only inside its murky frame.

Dirt and dregs, filth and silt.

Mother’s red and silver suitcase

Filled with old lottery tickets and photographs.

Everything behind us

Is before us

Stretched out: an endless

Grey horizon.

What we don’t remember,

Lives in us, forever.

From Guidebooks for the Dead (Four Way Books, 2020). Reprinted with the permission of the author and publisher.

On “Guidebooks for the Dead”

This poem, “Guidebooks for the Dead” is one of a series of poems of the same title.

The poem begins mid-conversation: “Or the beginnings of deadly illness,” addressing the subject of illness as a by-product of poverty. Illness that results from years of living with malnutrition and its related diseases of diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and then the maladies of despair: alcoholism, drug addiction, and depression. Years, indeed generations, of living in poverty result in generational trauma. This poem, this collection, is an attempt at locating a language that might address and convey the conditions of the working class and the poor.

The poem is structured as a dream, though, of course it isn’t one: with overlapping images and themes to help the reader enter into the experience. I do not want the reader to feel herself outside the experience, looking from the outside in. I want the reader to walk into this world.

And without explanation. The risk, of course, is that the reader will think “This poem is ugly” or “This poem is negative”—-both of which are accurate reactions but have no meaning without the recognition that this is the exact reaction one has when being forced to see how the working class and the poor live. If the reader has this experience, if the reader walks away form this poem thinking the poem is negative, ugly, and depressing, then the work has succeeded.

The poem is a form of gesture: I do not have words to convey what I wish to. Furthermore, words of explanation will only reduce and diminish. Instead, I hope to show: the same way a child reduced to speechlessness points to a photograph to show how she feels.

In stanza two I include myself in the portrait of poverty and illness and include a list of objects that convey, for me, poverty:

I exist inside its murky frame.

Dirt and dreg, filth and silt.

The last four stanzas address both the trauma of generational poverty and the desire

to rid one’s self of this legacy:

Mother’s red and silver suitcase

Filled with old lottery tickets and photographs.

Everything behind us

Is before

Stretched out: an endless

Grey horizon.

What we don't remember,

Lives in us, forever.

Attempts to move out of one’s social class, in the US, are quite futile as is attempting to pretend that one is not from the working class. We are formed by our experiences but also generational trauma lives inside us, informing our every moment. Trauma creates forgetfulness: as Freud points out: what the psyche cannot handle, the mind banishes. But the remnants, the detritus of trauma remains within us, rendering us speechless, unable to articulate the trauma which now has no context, no narrative.

This poem, written sometime between 2013-2015, is an attempt at something I have been thinking about a lot lately: how to write about reality without sliding into nihilism. I have come to believe that beauty and mystery are necessary because both reside in the world, even in the worst catastrophes. Furthermore, beauty and mystery are found through curiosity—a necessary element in poetry. But also a necessary element for living life awake and alive—and curiosity is a sign of hope, which counteracts nihilism. Finally, hope is not optimism which is, it seems, a form of resisting reality. The optimist says Things are going to be okay,” which is often not the case. Hope says there is always something to look at, to see, even in the worst calamities. Even during war there is a bird, children, the moon and trees.